Finn Brunton in Cabinet:

The history of digital cash consists of scientific discoveries from the 1970s, hardware from the 1980s, and networks from the 1990s, shaped by theories from the previous three centuries and beliefs about the next ten thousand years. It speaks ancient ideas with a modern twang, as we might when we say “quid pro quo” or “shibboleth”: the sovereign right to issue money, the debasement of coinage, the symbolic stamp that transfers the rights to value from me to thee. Digital cash has the hovering, unsettled realness (not reality) of all money, a matter of life and death that is also symbolic tokens, rules of a game, scraps of cotton blend and polymer, entries in a database, promises made and broken, gestures of affection and trust. The long history we are discussing here is at its heart the history of a debate about knowledge, an epistemological argument conducted through technologies.

The history of digital cash consists of scientific discoveries from the 1970s, hardware from the 1980s, and networks from the 1990s, shaped by theories from the previous three centuries and beliefs about the next ten thousand years. It speaks ancient ideas with a modern twang, as we might when we say “quid pro quo” or “shibboleth”: the sovereign right to issue money, the debasement of coinage, the symbolic stamp that transfers the rights to value from me to thee. Digital cash has the hovering, unsettled realness (not reality) of all money, a matter of life and death that is also symbolic tokens, rules of a game, scraps of cotton blend and polymer, entries in a database, promises made and broken, gestures of affection and trust. The long history we are discussing here is at its heart the history of a debate about knowledge, an epistemological argument conducted through technologies.

It is a debate broadly familiar to anyone who has taken an interest in the nature of money, or even looked idly at a banknote for a bit: how do I know that money is real? I want to phrase the question in this somewhat awkward way to capture how it can be reasonably answered. We can ask it at the level of a particular token of money—how do I know this money is real?—with the feel and texture of a note, the security threads, watermarks, and ultraviolet inks. We can ask it at the level of some type or variety of money, perhaps expressed as a preference for one currency as more “solid” than another, for instance, or for cash over credit, or gold over both: how do I know this kind of money is real? Finally, we can ask it at the level of money as such—what is money that it has value for us, and how do we know that value? How do I know that money is real?

More here.

For almost a year, the central policy debate in most Western countries has been whether—and for how long—to impose lockdowns. Advocates of stringent lockdowns argue that measures such as stay-at-home orders and forced closures of businesses are necessary to save lives and prevent health-care systems from being overwhelmed. So-called “lockdown sceptics,” on the other hand, argue either that such measures are ineffective, or that their benefits are outweighed by the associated social and economic costs; and that a focussed protection strategy is preferable. (The term “lockdown,” as I am using it, does not encompass all non-pharmaceutical interventions. In particular, I am excluding non-onerous, common-sense measures like asking symptomatic individuals to self-isolate, encouraging vulnerable people to work from home, and restricting large indoor gatherings.)

For almost a year, the central policy debate in most Western countries has been whether—and for how long—to impose lockdowns. Advocates of stringent lockdowns argue that measures such as stay-at-home orders and forced closures of businesses are necessary to save lives and prevent health-care systems from being overwhelmed. So-called “lockdown sceptics,” on the other hand, argue either that such measures are ineffective, or that their benefits are outweighed by the associated social and economic costs; and that a focussed protection strategy is preferable. (The term “lockdown,” as I am using it, does not encompass all non-pharmaceutical interventions. In particular, I am excluding non-onerous, common-sense measures like asking symptomatic individuals to self-isolate, encouraging vulnerable people to work from home, and restricting large indoor gatherings.) Yeats saw so deeply into the contours of his age that the shape of the future became somewhat discernible. He understood that those who merely reflect the nostra of their times soon go out of fashion (“like an old song”), but that those who oppose the spirit of their age often capture its central energies and come to know it from within. In doing as much, they may imagine the sort of future world to which a dreamer will awaken (“In dreams begin responsibility”).

Yeats saw so deeply into the contours of his age that the shape of the future became somewhat discernible. He understood that those who merely reflect the nostra of their times soon go out of fashion (“like an old song”), but that those who oppose the spirit of their age often capture its central energies and come to know it from within. In doing as much, they may imagine the sort of future world to which a dreamer will awaken (“In dreams begin responsibility”). Don’t think yourself odd if, after reading the Danish writer Tove Ditlevsen’s romantic, spiritually macabre, and ultimately devastating collection of memoirs, “

Don’t think yourself odd if, after reading the Danish writer Tove Ditlevsen’s romantic, spiritually macabre, and ultimately devastating collection of memoirs, “ Teenagers are so vulnerable. Like ripe peaches, they’re too easily bruised. But Alisson Wood was more defenceless than most. At 17, she had already undergone ECT in an effort to treat her depression; beneath her clothes, her arms bore the marks of self-harm. If her American high school was a place to be endured – the other girls, in their locker-room sententiousness, had decided she was a “psycho” – home was hardly a refuge. Her parents, who would soon divorce, were more preoccupied with their own troubles than with those of their exhausting, Sylvia Plath-loving daughter.

Teenagers are so vulnerable. Like ripe peaches, they’re too easily bruised. But Alisson Wood was more defenceless than most. At 17, she had already undergone ECT in an effort to treat her depression; beneath her clothes, her arms bore the marks of self-harm. If her American high school was a place to be endured – the other girls, in their locker-room sententiousness, had decided she was a “psycho” – home was hardly a refuge. Her parents, who would soon divorce, were more preoccupied with their own troubles than with those of their exhausting, Sylvia Plath-loving daughter. The inspiration to bring out a new edition of Cedric Robinson’s classic, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, came from the estimated 26 million people who took to the streets during the spring and summer of 2020 to protest the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and the many others who lost their lives to the police. During this time, the world bore witness to the Black radical tradition in motion, driving what was arguably the most dynamic mass rebellion against state-sanctioned violence and racial capitalism we have seen in North America since the 1960s—maybe the 1860s. The boldest activists demanded that we abolish police and prisons and shift the resources funding police and prisons to housing, universal healthcare, living-wage jobs, universal basic income, green energy, and a system of restorative justice. These new abolitionists are not interested in making capitalism fairer, safer, and less racist—they know this is impossible. They want to bring an end to “racial capitalism.”

The inspiration to bring out a new edition of Cedric Robinson’s classic, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, came from the estimated 26 million people who took to the streets during the spring and summer of 2020 to protest the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and the many others who lost their lives to the police. During this time, the world bore witness to the Black radical tradition in motion, driving what was arguably the most dynamic mass rebellion against state-sanctioned violence and racial capitalism we have seen in North America since the 1960s—maybe the 1860s. The boldest activists demanded that we abolish police and prisons and shift the resources funding police and prisons to housing, universal healthcare, living-wage jobs, universal basic income, green energy, and a system of restorative justice. These new abolitionists are not interested in making capitalism fairer, safer, and less racist—they know this is impossible. They want to bring an end to “racial capitalism.” Lately, I’ve found myself wondering if the time spent in lockdown is going to be memorable or if it’s just going to be one long blur of days spent more or less the same way—waking up, staring, trying to work, forgetting to do things, drinking, sleeping. Even the initial flood of pieces about the lockdown experience has mostly dried up, replaced by tweets in which people confess not to know how to get through the sameness of each predictable tomorrow. There’s nothing to say about nothing. Furthermore, no one wants to read about it. No one even wants to write about it (though here I am anyway).

Lately, I’ve found myself wondering if the time spent in lockdown is going to be memorable or if it’s just going to be one long blur of days spent more or less the same way—waking up, staring, trying to work, forgetting to do things, drinking, sleeping. Even the initial flood of pieces about the lockdown experience has mostly dried up, replaced by tweets in which people confess not to know how to get through the sameness of each predictable tomorrow. There’s nothing to say about nothing. Furthermore, no one wants to read about it. No one even wants to write about it (though here I am anyway). A common argument against free will is that human behavior is not freely chosen, but rather determined by a number of factors. So what are those factors, anyway? There’s no one better equipped to answer this question than Robert Sapolsky, a leading psychoneurobiologist who has studied human behavior from a variety of angles. In this conversation we follow the path Sapolsky sets out in his bestselling book

A common argument against free will is that human behavior is not freely chosen, but rather determined by a number of factors. So what are those factors, anyway? There’s no one better equipped to answer this question than Robert Sapolsky, a leading psychoneurobiologist who has studied human behavior from a variety of angles. In this conversation we follow the path Sapolsky sets out in his bestselling book  In 2020, President Donald Trump received more votes, almost 75 million, than any sitting president in U.S. history. And yet he lost the popular vote to Joe Biden, who received more votes than any presidential candidate in U.S. history—full stop. The 2020 election will thus go down in history as one in which Americans were both remarkably mobilized and sharply divided.

In 2020, President Donald Trump received more votes, almost 75 million, than any sitting president in U.S. history. And yet he lost the popular vote to Joe Biden, who received more votes than any presidential candidate in U.S. history—full stop. The 2020 election will thus go down in history as one in which Americans were both remarkably mobilized and sharply divided. In contrast to the gut, which offers a near-ideal habitat for the growth of fermentative bacteria, the skin is an inhospitable expanse. Much of the epidermal layer that protects humans from the elements is dry, salty, acidic and nutrient-poor. The exceptions are the oases around lipid-rich hair follicles. Despite this adversity, a diverse and physiologically important array of bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea make their home on the skin. Typically, a person has around 1,000 species of bacteria on their skin. And, as might be expected from such a large area — roughly two square metres for an average adult — the skin offers a variety of distinct ecosystems, which create conditions that favour different subsets of organisms.

In contrast to the gut, which offers a near-ideal habitat for the growth of fermentative bacteria, the skin is an inhospitable expanse. Much of the epidermal layer that protects humans from the elements is dry, salty, acidic and nutrient-poor. The exceptions are the oases around lipid-rich hair follicles. Despite this adversity, a diverse and physiologically important array of bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea make their home on the skin. Typically, a person has around 1,000 species of bacteria on their skin. And, as might be expected from such a large area — roughly two square metres for an average adult — the skin offers a variety of distinct ecosystems, which create conditions that favour different subsets of organisms. From December 31, 1957 until December 31, 1967, the artist and writer Henry Darger (1892–1973) kept a series of six ring-binder notebooks with almost daily entries on the weather in his native Chicago. On the outside cover of the first book, Darger describes the project, with encyclopedic enthusiasm, as a “book of weather reports on temperatures, fair cloudy to clear skies, snow, rain, or summer storms, and winter snows and big blizzards—also the low temperatures of severe cold waves and hot spells of summer.”

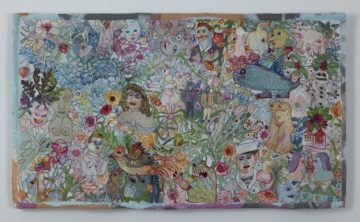

From December 31, 1957 until December 31, 1967, the artist and writer Henry Darger (1892–1973) kept a series of six ring-binder notebooks with almost daily entries on the weather in his native Chicago. On the outside cover of the first book, Darger describes the project, with encyclopedic enthusiasm, as a “book of weather reports on temperatures, fair cloudy to clear skies, snow, rain, or summer storms, and winter snows and big blizzards—also the low temperatures of severe cold waves and hot spells of summer.” Angels, devils, dragons, and monsters are just a few of the unruly creatures that maraud across

Angels, devils, dragons, and monsters are just a few of the unruly creatures that maraud across  Black feminist thought has become crucial to how we navigate the social, economic, and political currents in America. To understand the consequences of pervasive racist narratives that seep into mainstream media – as well as into public policy and legislation – we must first examine how these narratives affect one of this country’s most vulnerable populations: Black women.

Black feminist thought has become crucial to how we navigate the social, economic, and political currents in America. To understand the consequences of pervasive racist narratives that seep into mainstream media – as well as into public policy and legislation – we must first examine how these narratives affect one of this country’s most vulnerable populations: Black women. As the pandemic raged in 2020, my boyfriend and I were confined within the closed quarters of my two-bedroom flat in Delhi. When the claustrophobia got too heavy, I would step out to rediscover the pleasure of walking with a sense of calm. I would try — and regularly fail — to meet my pre-pandemic mark of eight kilometers every day. It was not a means to an end. I did not have a grand plan. It was just a way to be a part of the city.

As the pandemic raged in 2020, my boyfriend and I were confined within the closed quarters of my two-bedroom flat in Delhi. When the claustrophobia got too heavy, I would step out to rediscover the pleasure of walking with a sense of calm. I would try — and regularly fail — to meet my pre-pandemic mark of eight kilometers every day. It was not a means to an end. I did not have a grand plan. It was just a way to be a part of the city.