Jennifer Szalai in The New York Times:

For a critic, there’s maybe nothing so central but also confounding as the question of taste — why we like what we like, and whether it’s something we decide for ourselves, based purely on our own freedom and idiosyncracies; or if our tastes can be shaped and even scripted, influenced by earnest argument, entrenched biases or cynical manipulation.

For a critic, there’s maybe nothing so central but also confounding as the question of taste — why we like what we like, and whether it’s something we decide for ourselves, based purely on our own freedom and idiosyncracies; or if our tastes can be shaped and even scripted, influenced by earnest argument, entrenched biases or cynical manipulation.

With “Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound,” Daphne A. Brooks blurs and eventually explodes this binary. She argues that “taste-making” has often served to enshrine a musical canon that skews white and male; at the same time, she emphasizes the importance of canon-building and does some taste-making of her own. The old guard might have deigned to make room for “Satchmo, Monk, Miles and Trane,” she writes, but it still seems hesitant to “imagine a pop (culture) life with Black women at its full-stop center rather than as the opening act, the accompanying act or the afterthought.”

There are a number of recent and forthcoming books by Black women — among them Maureen Mahon, Danyel Smith and Clover Hope — that elucidate the central role that Black women artists have played in American music. Brooks, who teaches at Yale, is explicit about wanting to connect two worlds that would seem to be distinct: those of intellectual theory and commercial appeal. One doesn’t have to exclude the other, she says, even if traditional rock criticism has supposed that market success must come at the expense of that vague and vaunted quality known as “authenticity.”

More here. (Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to honoring Black History Month. The theme this year is: The Family)

1. Always refer to Iran as the “Islamic Republic” and its government as “the regime” or, better yet, “the Mullahs.”

1. Always refer to Iran as the “Islamic Republic” and its government as “the regime” or, better yet, “the Mullahs.”

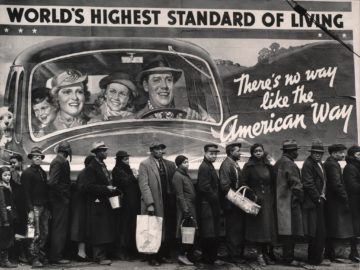

The anti-government stinginess of traditional conservatism, along with the fear of losing social status held by many white people, now broadly associated with Trumpism, have long been connected. Both have sapped American society’s strength for generations, causing a majority of white Americans to rally behind the draining of public resources and investments. Those very investments would provide white Americans — the largest group of the impoverished and uninsured — greater security, too: A new Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco study

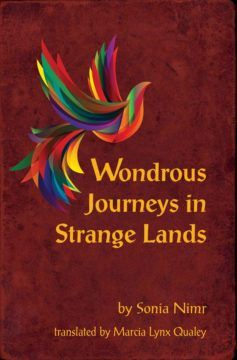

The anti-government stinginess of traditional conservatism, along with the fear of losing social status held by many white people, now broadly associated with Trumpism, have long been connected. Both have sapped American society’s strength for generations, causing a majority of white Americans to rally behind the draining of public resources and investments. Those very investments would provide white Americans — the largest group of the impoverished and uninsured — greater security, too: A new Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco study  I grew up in one of those small Palestinian villages where some of Nimr’s readership likely stems from, quite close to where Nimr teaches. I read plenty of kid-lit on my way to school (and at school when I was supposed to be paying attention); I went on adventures with dragons and later, I traveled into deep space. I could have used a heroine like Qamar when I was younger to encourage me to step outside of my own reality. Not only does she look like me, Qamar feels written for me. I see much of my upbringing in Qamar, in how I approach rest, play, work, and curiosity, even perhaps how I approach being a woman. Qamar moves at her own pace, and while she is concerned with survival, she also understands how to adapt, when to let something bizarre and even unjust become normalized, and when that is no longer acceptable.

I grew up in one of those small Palestinian villages where some of Nimr’s readership likely stems from, quite close to where Nimr teaches. I read plenty of kid-lit on my way to school (and at school when I was supposed to be paying attention); I went on adventures with dragons and later, I traveled into deep space. I could have used a heroine like Qamar when I was younger to encourage me to step outside of my own reality. Not only does she look like me, Qamar feels written for me. I see much of my upbringing in Qamar, in how I approach rest, play, work, and curiosity, even perhaps how I approach being a woman. Qamar moves at her own pace, and while she is concerned with survival, she also understands how to adapt, when to let something bizarre and even unjust become normalized, and when that is no longer acceptable. We realize then that from the fantastic opening image of the sea whom the poet would like to invite in, like a good neighbor, to have a coffee, to the powerful ending of “All of It,” each line of Exhausted on the Cross is the scene of a physical fight, to the death, between words and what we can no longer say. We cannot express the tension of that centimeter that separates us from the woman from Shatila. There are no words to name the absolute horror, to account for the exact moment in which the body of a living child becomes the body of a slaughtered child, we lack images to fix that infinitesimal second in which someone becomes those lumps of flesh and bone thrown into the sea by Latin American dictators, or the heaps of scattered limbs of Palestinians crushed by Israeli bombs in Gaza, or those massacred in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. We have no concepts to imagine what questions, what memories assail someone in that monstrous extreme, someone being killed by other men. And yet, for that very reason, precisely because those words do not exist, they must be shouted, to bring to this side of the world the terrible and ruthless porosity of each of those moments.

We realize then that from the fantastic opening image of the sea whom the poet would like to invite in, like a good neighbor, to have a coffee, to the powerful ending of “All of It,” each line of Exhausted on the Cross is the scene of a physical fight, to the death, between words and what we can no longer say. We cannot express the tension of that centimeter that separates us from the woman from Shatila. There are no words to name the absolute horror, to account for the exact moment in which the body of a living child becomes the body of a slaughtered child, we lack images to fix that infinitesimal second in which someone becomes those lumps of flesh and bone thrown into the sea by Latin American dictators, or the heaps of scattered limbs of Palestinians crushed by Israeli bombs in Gaza, or those massacred in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. We have no concepts to imagine what questions, what memories assail someone in that monstrous extreme, someone being killed by other men. And yet, for that very reason, precisely because those words do not exist, they must be shouted, to bring to this side of the world the terrible and ruthless porosity of each of those moments. The names most associated with Black Lives Matter are not its leaders but the victims who have drawn attention to the massive issues of racism this country grapples with: George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, to name a few. The movement can be traced back to 2013, after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who shot and killed Trayvon Martin in Florida. The 17-year-old had been returning from a shop after buying sweets and iced tea. Mr Zimmerman claimed the unarmed black teenager had looked suspicious. There was outrage when he was found not guilty of murder, and a Facebook post entitled “Black Lives Matter” captured a mood and sparked action.

The names most associated with Black Lives Matter are not its leaders but the victims who have drawn attention to the massive issues of racism this country grapples with: George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, to name a few. The movement can be traced back to 2013, after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who shot and killed Trayvon Martin in Florida. The 17-year-old had been returning from a shop after buying sweets and iced tea. Mr Zimmerman claimed the unarmed black teenager had looked suspicious. There was outrage when he was found not guilty of murder, and a Facebook post entitled “Black Lives Matter” captured a mood and sparked action. ON MARCH 6,

ON MARCH 6, There are many kinds of pseudosciences: astrology, homeopathy, flat-Earthism, anti-vaxx. These ‘fields’ traffic in bizarre claims with scientific pretensions. On a surface level, these claims seem to be scientific and usually appear to comment on the same kind of things that science does. However, upon closer inspection, pseudoscience is revealed to be

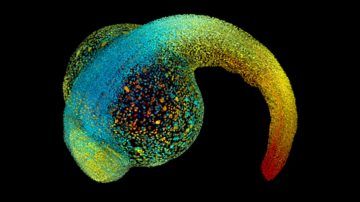

There are many kinds of pseudosciences: astrology, homeopathy, flat-Earthism, anti-vaxx. These ‘fields’ traffic in bizarre claims with scientific pretensions. On a surface level, these claims seem to be scientific and usually appear to comment on the same kind of things that science does. However, upon closer inspection, pseudoscience is revealed to be  At first, an embryo has no front or back, head or tail. It’s a simple sphere of cells. But soon enough, the smooth clump begins to change. Fluid pools in the middle of the sphere. Cells flow like honey to take up their positions in the future body. Sheets of cells fold origami-style, building a heart, a gut, a brain.

At first, an embryo has no front or back, head or tail. It’s a simple sphere of cells. But soon enough, the smooth clump begins to change. Fluid pools in the middle of the sphere. Cells flow like honey to take up their positions in the future body. Sheets of cells fold origami-style, building a heart, a gut, a brain. First things first — much respect to Bill Gates for his membership in the select club of ultrabillionaires not actively attempting to flee Earth and colonize Mars. His affection for his home planet and the people on it shines through clearly in this new book, as does his proud and usually endearing geekiness. The book’s illustrations include photos of him inspecting industrial facilities, like a fertilizer distribution plant in Tanzania; definitely the happiest picture is of him and his son grinning identical grins outside an Icelandic geothermal power station. “Rory and I used to visit power plants for fun,” he writes, “just to learn how they worked.”

First things first — much respect to Bill Gates for his membership in the select club of ultrabillionaires not actively attempting to flee Earth and colonize Mars. His affection for his home planet and the people on it shines through clearly in this new book, as does his proud and usually endearing geekiness. The book’s illustrations include photos of him inspecting industrial facilities, like a fertilizer distribution plant in Tanzania; definitely the happiest picture is of him and his son grinning identical grins outside an Icelandic geothermal power station. “Rory and I used to visit power plants for fun,” he writes, “just to learn how they worked.” A consensus has emerged in recent years that psychotherapies—in particular, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—rate comparably to medications such as Prozac and Lexapro as treatments for depression. Either option, or the two together, may at times alleviate the mood disorder. In looking more closely at both treatments, CBT—which delves into dysfunctional thinking patterns—may have a benefit that could make it the better choice for a patient.

A consensus has emerged in recent years that psychotherapies—in particular, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—rate comparably to medications such as Prozac and Lexapro as treatments for depression. Either option, or the two together, may at times alleviate the mood disorder. In looking more closely at both treatments, CBT—which delves into dysfunctional thinking patterns—may have a benefit that could make it the better choice for a patient. When 22-year-old Cassius Clay

When 22-year-old Cassius Clay  “How did you reach adulthood without learning how to cook?”

“How did you reach adulthood without learning how to cook?”