Anne Enright in The Guardian:

Klara and the Sun asks readers to love a robot and, the funny thing is, we do. This is a novel not just about a machine but narrated by a machine, though the word is not used about her until late in the book when it is wielded by a stranger as an insult. People distrust and then start to like her: “Are you alright, Klara?” Apart from the occasional lapse into bullying or indifference, humans are solicitous of Klara’s feelings – if that is what they are. Klara is built to observe and understand humans, and these actions are so close to empathy they may amount to the same thing. “I believe I have many feelings,” she says. “The more I observe the more feelings become available to me.” Klara is an AF, or artificial friend, who is bought as a companion for 14-year-old Josie, a girl suffering from a mysterious, perhaps terminal illness. Klara is loyal and tactful, she is able to absorb difficulty and return care. Her role, as she describes it, is to prevent loneliness and to serve.

Klara and the Sun asks readers to love a robot and, the funny thing is, we do. This is a novel not just about a machine but narrated by a machine, though the word is not used about her until late in the book when it is wielded by a stranger as an insult. People distrust and then start to like her: “Are you alright, Klara?” Apart from the occasional lapse into bullying or indifference, humans are solicitous of Klara’s feelings – if that is what they are. Klara is built to observe and understand humans, and these actions are so close to empathy they may amount to the same thing. “I believe I have many feelings,” she says. “The more I observe the more feelings become available to me.” Klara is an AF, or artificial friend, who is bought as a companion for 14-year-old Josie, a girl suffering from a mysterious, perhaps terminal illness. Klara is loyal and tactful, she is able to absorb difficulty and return care. Her role, as she describes it, is to prevent loneliness and to serve.

…There is something so steady and beautiful about the way Klara is always approaching connection, like a Zeno’s arrow of the heart. People will absolutely love this book, in part because it enacts the way we learn how to love. Klara and the Sun is wise like a child who decides, just for a little while, to love their doll. “What can children know about genuine love?” Klara asks. The answer, of course, is everything.

More here.

Transitional justice is both a legal and philosophical

Transitional justice is both a legal and philosophical  This is the familiar arc that Jonathan Sadowsky traces in his new book The Empire of Depression: A New History. But Sadowsky, a medical historian at Case Western, aims to show how the Western notion of depression is making its way around the globe, threatening to displace other conceptions of the disease. “Western psychiatry often treats anxiety and depression as separate things that often occur together. In many places, though, anxiety and depression are seen as part of one thing,” he writes. And the sense of what causes depression differs significantly, too. Whereas in the West, depression is most often understood as having a physical reason, be it genes, or chemistry, “globally, it is more common to consider depression to be at once psychological, social, and physical.”

This is the familiar arc that Jonathan Sadowsky traces in his new book The Empire of Depression: A New History. But Sadowsky, a medical historian at Case Western, aims to show how the Western notion of depression is making its way around the globe, threatening to displace other conceptions of the disease. “Western psychiatry often treats anxiety and depression as separate things that often occur together. In many places, though, anxiety and depression are seen as part of one thing,” he writes. And the sense of what causes depression differs significantly, too. Whereas in the West, depression is most often understood as having a physical reason, be it genes, or chemistry, “globally, it is more common to consider depression to be at once psychological, social, and physical.” “IMAGINE, IF YOU CAN, a small room, hexagonal in shape, like the cell of a bee.” So begins a story by E. M. Forster from over a century ago, about a future that feels uncannily like our present. Called “The Machine Stops,” the story conjures a world of individual humans isolated in such rooms who pass the time by streaming lectures and videoconferencing as the titular Machine tends to their every need. It is a world in which everything — music, food, even your bed — is summoned by the click of a button. In place of work, the Machine offers material and intellectual sustenance. For the story’s main character, Vashti, it turns life into a reassuringly predictable cycle: “[S]he made the room dark and slept; she awoke and made the room light; she ate and exchanged ideas with her friends, and listened to music and attended lectures; she made the room dark and slept. Above her, beneath her, and around her, the Machine hummed eternally.” To Vashti, the Machine offers serenity and certainty in equal measure. In this imagined world of isolated togetherness, heaven is a place.

“IMAGINE, IF YOU CAN, a small room, hexagonal in shape, like the cell of a bee.” So begins a story by E. M. Forster from over a century ago, about a future that feels uncannily like our present. Called “The Machine Stops,” the story conjures a world of individual humans isolated in such rooms who pass the time by streaming lectures and videoconferencing as the titular Machine tends to their every need. It is a world in which everything — music, food, even your bed — is summoned by the click of a button. In place of work, the Machine offers material and intellectual sustenance. For the story’s main character, Vashti, it turns life into a reassuringly predictable cycle: “[S]he made the room dark and slept; she awoke and made the room light; she ate and exchanged ideas with her friends, and listened to music and attended lectures; she made the room dark and slept. Above her, beneath her, and around her, the Machine hummed eternally.” To Vashti, the Machine offers serenity and certainty in equal measure. In this imagined world of isolated togetherness, heaven is a place. The spiritual godfather of the Beat movement, Mr. Ferlinghetti made his home base in the modest independent book haven now formally known as City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. A self-described “literary meeting place” founded in 1953 and located on the border of the city’s sometimes swank, sometimes seedy North Beach neighborhood, City Lights, on Columbus Avenue, soon became as much a part of the San Francisco scene as the Golden Gate Bridge or Fisherman’s Wharf. (The city’s board of supervisors designated it a historic landmark in 2001.)

The spiritual godfather of the Beat movement, Mr. Ferlinghetti made his home base in the modest independent book haven now formally known as City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. A self-described “literary meeting place” founded in 1953 and located on the border of the city’s sometimes swank, sometimes seedy North Beach neighborhood, City Lights, on Columbus Avenue, soon became as much a part of the San Francisco scene as the Golden Gate Bridge or Fisherman’s Wharf. (The city’s board of supervisors designated it a historic landmark in 2001.) Several years ago, workers breaking ground for a power plant in New Zealand

Several years ago, workers breaking ground for a power plant in New Zealand  The rise of China to the status of economic superpower has been the dominant narrative of the last three decades. China’s rise as the main feature of globalisation, in conjunction with a beneficial sweet spot in demography, drove output up and inflation down in the advanced economies. But these trends are now reversing. China’s economic success depended on many factors, a strong historical social and cultural background, political single-mindedness, a flexible and competent labour force, fed by internal migration, capital controls, developing satisfactory infrastructure and absorption of Western technological know-how. But China’s greatest contribution to global growth is now past. Its working age population is now shrinking, while the ranks of the old expands.

The rise of China to the status of economic superpower has been the dominant narrative of the last three decades. China’s rise as the main feature of globalisation, in conjunction with a beneficial sweet spot in demography, drove output up and inflation down in the advanced economies. But these trends are now reversing. China’s economic success depended on many factors, a strong historical social and cultural background, political single-mindedness, a flexible and competent labour force, fed by internal migration, capital controls, developing satisfactory infrastructure and absorption of Western technological know-how. But China’s greatest contribution to global growth is now past. Its working age population is now shrinking, while the ranks of the old expands. Dreams are full of possibilities; by drifting into the world beyond our waking realities, we can visit magical lands, travel through time and interact with long-lost family and friends. The notion of communicating in real time with someone outside of our dreamscapes, however, sounds like science fiction. A new study demonstrates that, to some extent, this seeming fantasy can be made real. Scientists already knew that one-way contact is attainable. Previous studies have demonstrated that people can process external cues, such as sounds and smells, while asleep. There is also evidence that people are able to send messages in the other direction: Lucid dreamers—those who can become aware they are in a dream—can be trained to signal, using eye movements, that they are in the midst of a dream. Two-way communication, however, is more complex. It requires a person who is asleep to actually understand what they hear from the outside and think about it logically enough to generate an answer, explains Ken Paller, a cognitive neuroscientist at Northwestern University. “We believed that it was going to be possible—but until we actually demonstrated it, we weren’t sure.”

Dreams are full of possibilities; by drifting into the world beyond our waking realities, we can visit magical lands, travel through time and interact with long-lost family and friends. The notion of communicating in real time with someone outside of our dreamscapes, however, sounds like science fiction. A new study demonstrates that, to some extent, this seeming fantasy can be made real. Scientists already knew that one-way contact is attainable. Previous studies have demonstrated that people can process external cues, such as sounds and smells, while asleep. There is also evidence that people are able to send messages in the other direction: Lucid dreamers—those who can become aware they are in a dream—can be trained to signal, using eye movements, that they are in the midst of a dream. Two-way communication, however, is more complex. It requires a person who is asleep to actually understand what they hear from the outside and think about it logically enough to generate an answer, explains Ken Paller, a cognitive neuroscientist at Northwestern University. “We believed that it was going to be possible—but until we actually demonstrated it, we weren’t sure.” Hinton Rowan Helper was an unreserved bigot from North Carolina who wrote hateful, racist tracts during Reconstruction. He was also, in the years leading up to the Civil War, a determined abolitionist.

Hinton Rowan Helper was an unreserved bigot from North Carolina who wrote hateful, racist tracts during Reconstruction. He was also, in the years leading up to the Civil War, a determined abolitionist. Study, reader, before going further,

Study, reader, before going further,  In our postmodern world, studying the classics of ancient Greece and Rome can seem quaint at best, downright repressive at worst. (We are talking about works by dead white men, after all.) Do we still have things to learn from classical philosophy, drama, and poetry? Shadi Bartsch offers a vigorous affirmative to this question in two new books coming from different directions. First, she has newly translated the

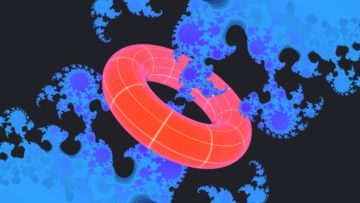

In our postmodern world, studying the classics of ancient Greece and Rome can seem quaint at best, downright repressive at worst. (We are talking about works by dead white men, after all.) Do we still have things to learn from classical philosophy, drama, and poetry? Shadi Bartsch offers a vigorous affirmative to this question in two new books coming from different directions. First, she has newly translated the  Joseph Silverman remembers when he began connecting the dots that would ultimately lead to a new branch of mathematics: April 25, 1992, at a conference at Union College in Schenectady, New York.

Joseph Silverman remembers when he began connecting the dots that would ultimately lead to a new branch of mathematics: April 25, 1992, at a conference at Union College in Schenectady, New York. In 2015, Bon Appétit

In 2015, Bon Appétit  Much of Cohen’s work is driven by his aversion to a type of spatial metaphor that minimises the value and variety of familiar experience. His first book, Spectacular Allegories (1998), a study of modern American fiction and journalism that emerged from his PhD, questions the postmodern idea that spectacle somehow floats “outside” history and “above” material reality. It was written before Cohen was a practitioner, or even employed Freudian theory. He told me that his “obsessional preoccupation – and I’m pointedly using the singular – has been what is concealed in what is right in front of us, in what is present”. He isn’t only talking about unconscious blind-spots. The book’s title is “filched”, as he puts it, from the American poet Wallace Stevens, and Cohen expressed a particular fondness for Stevens’s idea of a “strange presence that irradiates through the world that his poems are always gesturing towards and trying to get us to see”.

Much of Cohen’s work is driven by his aversion to a type of spatial metaphor that minimises the value and variety of familiar experience. His first book, Spectacular Allegories (1998), a study of modern American fiction and journalism that emerged from his PhD, questions the postmodern idea that spectacle somehow floats “outside” history and “above” material reality. It was written before Cohen was a practitioner, or even employed Freudian theory. He told me that his “obsessional preoccupation – and I’m pointedly using the singular – has been what is concealed in what is right in front of us, in what is present”. He isn’t only talking about unconscious blind-spots. The book’s title is “filched”, as he puts it, from the American poet Wallace Stevens, and Cohen expressed a particular fondness for Stevens’s idea of a “strange presence that irradiates through the world that his poems are always gesturing towards and trying to get us to see”. We knew that the persistent cough spelled his end. The fever had preceded it, just as it had in his mother, brother and dozens around him. The contagion that was devastating society had him in its throes. When he finally died, a postmortem showed his lungs had been decimated. He’d suffocated, drowning in his own inflammatory fluids. The young English poet

We knew that the persistent cough spelled his end. The fever had preceded it, just as it had in his mother, brother and dozens around him. The contagion that was devastating society had him in its throes. When he finally died, a postmortem showed his lungs had been decimated. He’d suffocated, drowning in his own inflammatory fluids. The young English poet