Hadley Freeman in The Guardian:

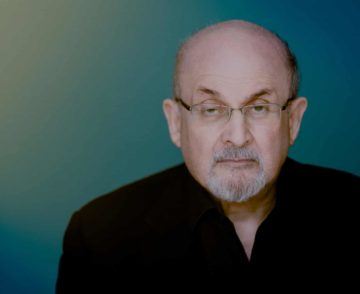

Poor Salman Rushdie. The one thing I am most keen to talk to him about is the one thing he absolutely, definitely does not want to discuss. “I really resist the idea of being dragged back to that period of time that you insist on bringing up,” he grumbles when I make the mistake of mentioning it twice in the first 15 minutes of our conversation. He is in his elegant, book-lined apartment, a cosy armchair just behind him, the corridor to the kitchen over his shoulder. He’s in New York, which has been his home for the past 20 years, and we are talking – as is the way these days – on video. But even through the screen his frustration is palpable, and I don’t blame him. He’s one of the most famous literary authors alive, having won pretty much every book prize on the planet, including the best of the Booker for Midnight’s Children. We’re meeting to talk about his latest book, Languages Of Truth, which is a collection of nonfiction from the last two decades, covering everything from Osama bin Laden to Linda Evangelista; from Cervantes to Covid. So why do I keep bringing up the fatwa?

Poor Salman Rushdie. The one thing I am most keen to talk to him about is the one thing he absolutely, definitely does not want to discuss. “I really resist the idea of being dragged back to that period of time that you insist on bringing up,” he grumbles when I make the mistake of mentioning it twice in the first 15 minutes of our conversation. He is in his elegant, book-lined apartment, a cosy armchair just behind him, the corridor to the kitchen over his shoulder. He’s in New York, which has been his home for the past 20 years, and we are talking – as is the way these days – on video. But even through the screen his frustration is palpable, and I don’t blame him. He’s one of the most famous literary authors alive, having won pretty much every book prize on the planet, including the best of the Booker for Midnight’s Children. We’re meeting to talk about his latest book, Languages Of Truth, which is a collection of nonfiction from the last two decades, covering everything from Osama bin Laden to Linda Evangelista; from Cervantes to Covid. So why do I keep bringing up the fatwa?

We try again. I want to do better because, really, he’s a lot of fun to chat to. Given his success and his history, pomposity should be a given, paranoia would be understandable. But this thoughtful man with an easy giggle is neither, as happy to talk about Field Of Dreams (“A very good film!”) as he is about Elena Ferrante, of whom he’s a fan. Also, Rushdie, 73, tells me, that since he recovered from Covid last spring, he’s been working on his first play. “Ooh, that’s exciting,” I say. “What’s it about?”

“Helen of Troy. It’s written in verse, and she’s interesting because all we really know about her is that she ran off with Paris. But who is she? Why does she do what she does? How does she feel about the consequences of her actions?”

More here.