Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

In her influential 1971 article, “A Defense of Abortion”,[1] the philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson deploys a number of outlandish thought experiments. Among them is the story of a woman much like herself who gets kidnapped and, on awakening, finds she is attached by complicated life-support apparatuses to a great violinist. Her kidnappers explain when she awakens that she happens to be just so physiologically constituted as to be necessary for the violinist’s survival, and surely she agrees it is important to keep this rare musician alive, does she not? If she gets up and walks away, he will die; if she stays attached to him for nine months, they will both live. But, they acknowledge, she is of course free to go.

In her influential 1971 article, “A Defense of Abortion”,[1] the philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson deploys a number of outlandish thought experiments. Among them is the story of a woman much like herself who gets kidnapped and, on awakening, finds she is attached by complicated life-support apparatuses to a great violinist. Her kidnappers explain when she awakens that she happens to be just so physiologically constituted as to be necessary for the violinist’s survival, and surely she agrees it is important to keep this rare musician alive, does she not? If she gets up and walks away, he will die; if she stays attached to him for nine months, they will both live. But, they acknowledge, she is of course free to go.

This particular scenario is one that Thomson only invokes in the course of making another point about another category of human beings than frail adult violinists, and yet it is a passing remark about his dependency on her that has preoccupied me the longest and most profoundly: we all agree, she reasons, that the person attached to the violinist is free to get up and leave, but she is not free to slit the violinist’s throat before going. Why not? The effect is the same in both cases —the violinist dies— and indeed a case could be made that killing him swiftly is more merciful than letting him die slowly.

More here.

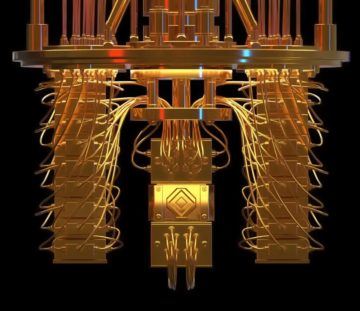

Quantum computers

Quantum computers As a new parent of boy/girl twins (at least as they were assigned at birth), I puzzle about the cultural pressure to scrutinise my infant son’s burgeoning masculinity lest it emerge as ‘toxic’. I catch myself watching and wondering, resisting the urge to police his interactions with his sister: He took the toy she was playing with, is this aggression that will stifle her confidence? She seems unbothered and has quickly snatched it back – phew! Is it bullying or an early form of manspreading when, both of them vying for the same object, he moves into her space and pushes her aside?

As a new parent of boy/girl twins (at least as they were assigned at birth), I puzzle about the cultural pressure to scrutinise my infant son’s burgeoning masculinity lest it emerge as ‘toxic’. I catch myself watching and wondering, resisting the urge to police his interactions with his sister: He took the toy she was playing with, is this aggression that will stifle her confidence? She seems unbothered and has quickly snatched it back – phew! Is it bullying or an early form of manspreading when, both of them vying for the same object, he moves into her space and pushes her aside? The saltwater aquarium in my new dentist’s office is its best feature. My favorite fish is a red fish with big eyes and a black stripe along its back. He has a generally grumpy demeanor, and I cannot help but feel a friendship form between us. I take photos of him and sometimes post them to Instagram. (“This red fish is my favorite fish, he is a total weirdo.”) He is popular among my friends.

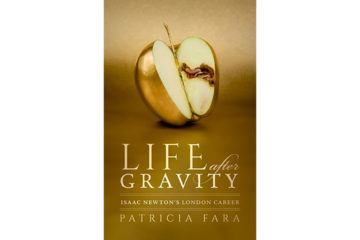

The saltwater aquarium in my new dentist’s office is its best feature. My favorite fish is a red fish with big eyes and a black stripe along its back. He has a generally grumpy demeanor, and I cannot help but feel a friendship form between us. I take photos of him and sometimes post them to Instagram. (“This red fish is my favorite fish, he is a total weirdo.”) He is popular among my friends. Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College. But even when Newton was performing his intellectual feats at Cambridge in the 1680s, he was eager to move on to a new life. Patricia Fara, historian of science at Cambridge University, seeks to chronicle that period in “Life after Gravity: Isaac Newton’s London Career.” In this book she presents Newton as “a metropolitan performer, a global actor who played various parts.”

Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College. But even when Newton was performing his intellectual feats at Cambridge in the 1680s, he was eager to move on to a new life. Patricia Fara, historian of science at Cambridge University, seeks to chronicle that period in “Life after Gravity: Isaac Newton’s London Career.” In this book she presents Newton as “a metropolitan performer, a global actor who played various parts.” Elham Saeidinezhad over at his website:

Elham Saeidinezhad over at his website: On the night of August 20, 1968, neighbors woke the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal and his wife, Eliška Plevová, to tell them that the Soviet Union was invading. Already their occupiers, the Soviets were now coming to put an end to the reforms of the Prague Spring. By morning, planes were flying low overhead, and soldiers and tanks filled the streets. One tank pointed its cannon directly at the offices of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers in Wenceslas Square. Hrabal, however, was eager to fulfill his duties as the best man at the wedding of his friend, the graphic artist Vladimír Boudník, in nearby Český Krumlov. “I set out in my car,” Hrabal writes in The Gentle Barbarian, “but I couldn’t get out of Prague, either through the city centre, or by using back routes, because the fraternal armies had arrived to liquidate something that was not there.” So he returned home, tried to attend a gallery show on modern American art (sorry, closed), and later relayed his troubles to his and Boudník’s mutual friend, the writer and philosopher Egon Bondy. Bondy, who called Hrabal by his nickname, Doctor, explodes in a frenzy of jealousy and admiration for Boudník:

On the night of August 20, 1968, neighbors woke the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal and his wife, Eliška Plevová, to tell them that the Soviet Union was invading. Already their occupiers, the Soviets were now coming to put an end to the reforms of the Prague Spring. By morning, planes were flying low overhead, and soldiers and tanks filled the streets. One tank pointed its cannon directly at the offices of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers in Wenceslas Square. Hrabal, however, was eager to fulfill his duties as the best man at the wedding of his friend, the graphic artist Vladimír Boudník, in nearby Český Krumlov. “I set out in my car,” Hrabal writes in The Gentle Barbarian, “but I couldn’t get out of Prague, either through the city centre, or by using back routes, because the fraternal armies had arrived to liquidate something that was not there.” So he returned home, tried to attend a gallery show on modern American art (sorry, closed), and later relayed his troubles to his and Boudník’s mutual friend, the writer and philosopher Egon Bondy. Bondy, who called Hrabal by his nickname, Doctor, explodes in a frenzy of jealousy and admiration for Boudník: Gideon Jones in Strife:

Gideon Jones in Strife: Robert Hockett in Forbes:

Robert Hockett in Forbes: T

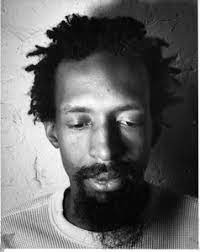

T Eastman died in 1990, at the age of forty-nine. Ebullient and confrontational in equal measure, he attended the Curtis Institute of Music, joined the Creative Associates program at the University of Buffalo, and found a degree of renown in avant-garde circles. In his final years, struggling with addiction, he faded from view. As a Black gay man, he encountered resistance and incomprehension during his lifetime. He is now experiencing a dizzying posthumous renaissance, to the point where his Symphony No. II is scheduled for the New York Philharmonic’s 2021-22 season.

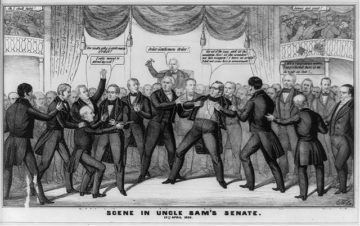

Eastman died in 1990, at the age of forty-nine. Ebullient and confrontational in equal measure, he attended the Curtis Institute of Music, joined the Creative Associates program at the University of Buffalo, and found a degree of renown in avant-garde circles. In his final years, struggling with addiction, he faded from view. As a Black gay man, he encountered resistance and incomprehension during his lifetime. He is now experiencing a dizzying posthumous renaissance, to the point where his Symphony No. II is scheduled for the New York Philharmonic’s 2021-22 season. The United States is not in the midst of a “culture war” over race and racism. The animating force of our current conflict is not our differing values, beliefs, moral codes, or practices. The American people aren’t divided. The American people are being divided. Republican operatives have

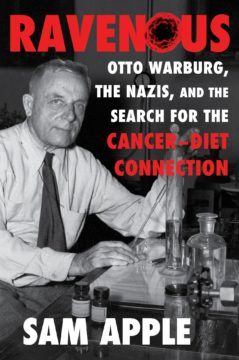

The United States is not in the midst of a “culture war” over race and racism. The animating force of our current conflict is not our differing values, beliefs, moral codes, or practices. The American people aren’t divided. The American people are being divided. Republican operatives have  When the Nazis seized power in March 1933, it was not unusual for major scientific institutes to be led by Nobel laureates with Jewish roots: Albert Einstein and Otto Meyerhof, both Jewish, ran prestigious centers of physics and medical research; Fritz Haber, who’d converted from Judaism in the late 19th century, ran a chemistry institute; and Otto Warburg, who was raised as a Protestant but had two Jewish grandparents, was the director of a recently opened center for cell physiology.

When the Nazis seized power in March 1933, it was not unusual for major scientific institutes to be led by Nobel laureates with Jewish roots: Albert Einstein and Otto Meyerhof, both Jewish, ran prestigious centers of physics and medical research; Fritz Haber, who’d converted from Judaism in the late 19th century, ran a chemistry institute; and Otto Warburg, who was raised as a Protestant but had two Jewish grandparents, was the director of a recently opened center for cell physiology.