Henry Nicholls in Nature:

Rich in meaning and metaphor, the word ‘heart’ conjures up many images: a pump, courage, kindness, love, a suit in a deck of cards, a shape or the most important part of an object or matter. These days, it also brings to mind the global increase in heart attacks and cardiovascular damage that attends COVID-19. As a subject for a book, the heart is an organ with a lot going for it.

Rich in meaning and metaphor, the word ‘heart’ conjures up many images: a pump, courage, kindness, love, a suit in a deck of cards, a shape or the most important part of an object or matter. These days, it also brings to mind the global increase in heart attacks and cardiovascular damage that attends COVID-19. As a subject for a book, the heart is an organ with a lot going for it.

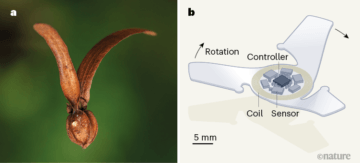

Enter zoologist Bill Schutt. His book Pump refuses to tie the heart off from the circulatory system, and instead uses it to explore how multicellular organisms have found various ways to solve the same fundamental challenge: satisfying the metabolic needs of cells that are beyond the reach of simple diffusion. He writes of the co-evolution of the circulatory and respiratory systems: “They cooperate, they depend on each other, and they are basically useless by themselves.” At his best, Schutt guides us on a journey from the origin of the first contractile cells more than 500 million years ago to the emergence of vertebrates, not long afterwards. He takes in, for example, horseshoe crabs, their blood coloured blue by the presence of the copper-based oxygen-transport protein haemocyanin (equivalent to humans’ iron-based haemoglobin).

We learn that insects, lacking a true heart, have a muscular dorsal vessel that bathes their tissues in blood-like haemolymph. Earthworms, too, are heartless but with a more complex arrangement of five pairs of contractile vessels. Squid and other cephalopods have three distinct hearts. The are plenty of zoological nuggets to enjoy along the way. The tubular heart of a sea squirt, for instance, contains pacemaker-like cells that enable it to pump in one direction and then the other. Some creatures need masses of oxygen, others little, leading to more diversity. The plethodontids (a group of salamanders) have neither lungs nor gills, he explains: their relatively small oxygen requirements are met by diffusion through the skin.

More here.

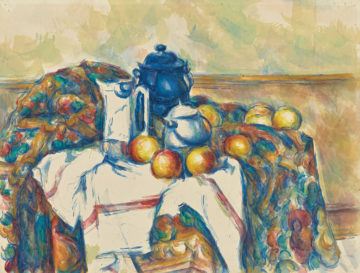

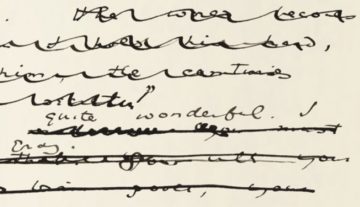

I’M NOT ONE FOR FLATTERY and hyperbole, especially when reacting to exhibitions. There is already enough sycophancy to go around on social media—even in the feeds of those who should know better. I am therefore going against every fiber of my being when I say that the Cézanne drawing show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art is unequivocally a once-in-a-generation not-to-be-missed event.

I’M NOT ONE FOR FLATTERY and hyperbole, especially when reacting to exhibitions. There is already enough sycophancy to go around on social media—even in the feeds of those who should know better. I am therefore going against every fiber of my being when I say that the Cézanne drawing show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art is unequivocally a once-in-a-generation not-to-be-missed event.

The Testing of Luther Albright (2005) and Traps (2013) are perfectly good novels if one has a taste for it. The second thing that needs to be noted about them is that, after her divorce from Jeff Bezos, founder and controlling shareholder of Amazon, their author is the richest woman in the world, or close enough, worth in excess (as I write these words) of $60 billion, mostly from her holdings of Amazon stock. She is no doubt the wealthiest published novelist of all time by a factor of … whatever, a high number. Compared to her, J. K. Rowling is still poor.

The Testing of Luther Albright (2005) and Traps (2013) are perfectly good novels if one has a taste for it. The second thing that needs to be noted about them is that, after her divorce from Jeff Bezos, founder and controlling shareholder of Amazon, their author is the richest woman in the world, or close enough, worth in excess (as I write these words) of $60 billion, mostly from her holdings of Amazon stock. She is no doubt the wealthiest published novelist of all time by a factor of … whatever, a high number. Compared to her, J. K. Rowling is still poor.  ELIZABETH HOLMES SAYS

ELIZABETH HOLMES SAYS  In

In  On December 15, 1929, Dr. Philip M. Lovell, the imperiously eccentric health columnist for the Los Angeles Times, invited readers to tour his ultramodern new home, at 4616 Dundee Drive, in the hills of Los Feliz. On a page crowded with ads promoting quack cures for “chronic constipation” and “sagging flabby chins,” Lovell announced three days of open houses, adding that “Mr. Richard T. Neutra, architect who designed and supervised the construction . . . will conduct the audience from room to room.” Neutra’s middle initial was actually J., but this recent Austrian immigrant, thirty-seven years old and underemployed, had little reason to complain: he was being launched as a pioneer of American modernist architecture. Thousands of people took the tour; striking photographs were published. Three years later, Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock, the codifiers of the International Style,

On December 15, 1929, Dr. Philip M. Lovell, the imperiously eccentric health columnist for the Los Angeles Times, invited readers to tour his ultramodern new home, at 4616 Dundee Drive, in the hills of Los Feliz. On a page crowded with ads promoting quack cures for “chronic constipation” and “sagging flabby chins,” Lovell announced three days of open houses, adding that “Mr. Richard T. Neutra, architect who designed and supervised the construction . . . will conduct the audience from room to room.” Neutra’s middle initial was actually J., but this recent Austrian immigrant, thirty-seven years old and underemployed, had little reason to complain: he was being launched as a pioneer of American modernist architecture. Thousands of people took the tour; striking photographs were published. Three years later, Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock, the codifiers of the International Style,  THE ARC THAT SAID HIMSELF

THE ARC THAT SAID HIMSELF We will be switching over to new servers today, Thursday, September 23, and this means we may not be able to post new items for a day or possibly longer. Thanks for your patience, and we’ll make the interruption as short as possible.

We will be switching over to new servers today, Thursday, September 23, and this means we may not be able to post new items for a day or possibly longer. Thanks for your patience, and we’ll make the interruption as short as possible. He died the day after Christmas. His loved ones washed and anointed his body and kept vigil at his bedside. “He looked like a king,” Jenifer told me. “He was really, really beautiful.” She showed me a few photos. His body had been laid atop a hemp shroud and covered from the neck down in a layer of dried herbs and flower petals. Bouquets of lavender and tree fronds wreathed his head, and a ladybug pendant on a beaded string lay across his brow like a diadem. Only his bearded face was exposed, wearing the peaceful, inscrutable expression of the dead. He did look like a king, or like a woodland deity out of Celtic mythology—his gauze-wrapped neck the only evidence of his life as a mortal.

He died the day after Christmas. His loved ones washed and anointed his body and kept vigil at his bedside. “He looked like a king,” Jenifer told me. “He was really, really beautiful.” She showed me a few photos. His body had been laid atop a hemp shroud and covered from the neck down in a layer of dried herbs and flower petals. Bouquets of lavender and tree fronds wreathed his head, and a ladybug pendant on a beaded string lay across his brow like a diadem. Only his bearded face was exposed, wearing the peaceful, inscrutable expression of the dead. He did look like a king, or like a woodland deity out of Celtic mythology—his gauze-wrapped neck the only evidence of his life as a mortal. The one thing you can say for sure about Katie Kitamura’s wonderfully sly new novel – the follow-up to her 2017 breakthrough A Separation, and one of Barack Obama’s summer reading picks – is that it offers a portrait of limbo. The unnamed narrator, a Japanese woman raised in Europe, has accepted a one-year contract as an interpreter at the International Criminal Court – identified only as “the Court” – in The Hague. The book’s title – which, like that of its predecessor, rejects the firmness of the definite article – refers to the relationship one might ideally have with language, spaces, customs, other people, one’s own emotions, the past. It’s unclear, at least at first, to what degree the character’s own failure to achieve this state herself is a product of temperament or circumstances – whether she is simply adjusting, or whether this is how she always presents, and negotiates, the world.

The one thing you can say for sure about Katie Kitamura’s wonderfully sly new novel – the follow-up to her 2017 breakthrough A Separation, and one of Barack Obama’s summer reading picks – is that it offers a portrait of limbo. The unnamed narrator, a Japanese woman raised in Europe, has accepted a one-year contract as an interpreter at the International Criminal Court – identified only as “the Court” – in The Hague. The book’s title – which, like that of its predecessor, rejects the firmness of the definite article – refers to the relationship one might ideally have with language, spaces, customs, other people, one’s own emotions, the past. It’s unclear, at least at first, to what degree the character’s own failure to achieve this state herself is a product of temperament or circumstances – whether she is simply adjusting, or whether this is how she always presents, and negotiates, the world. The historian Joe Moran begins his 2018 style guide, First You Write a Sentence, by outlining a comic routine unfortunately familiar to many of us:

The historian Joe Moran begins his 2018 style guide, First You Write a Sentence, by outlining a comic routine unfortunately familiar to many of us: Back in 2000, when

Back in 2000, when  I travelled to New York City in August for the first time since the pandemic began, to visit friends who had just bought their first home. They are firmly upper-middle class and in their 40s. They took out a mortgage for $1.5m (£1.1m) to buy a place in a Brooklyn neighbourhood that was regarded until recently as an area immune to gentrification. So far, so typical. Asset ownership comes late these days.

I travelled to New York City in August for the first time since the pandemic began, to visit friends who had just bought their first home. They are firmly upper-middle class and in their 40s. They took out a mortgage for $1.5m (£1.1m) to buy a place in a Brooklyn neighbourhood that was regarded until recently as an area immune to gentrification. So far, so typical. Asset ownership comes late these days. Rich in meaning and metaphor, the word ‘heart’ conjures up many images: a pump, courage, kindness, love, a suit in a deck of cards, a shape or the most important part of an object or matter. These days, it also brings to mind the global increase in heart attacks and cardiovascular damage that attends COVID-19. As a subject for a book, the heart is an organ with a lot going for it.

Rich in meaning and metaphor, the word ‘heart’ conjures up many images: a pump, courage, kindness, love, a suit in a deck of cards, a shape or the most important part of an object or matter. These days, it also brings to mind the global increase in heart attacks and cardiovascular damage that attends COVID-19. As a subject for a book, the heart is an organ with a lot going for it. What is found in a good conversation? It is certainly correct to say words—the more engagingly put, the better. But conversation also includes “eyes, smiles, the silences between the words,” as the Swedish author Annika Thor wrote. It is when those elements hum along together that we feel most deeply engaged with, and most connected to, our conversational partner, as if we are in sync with them. Like good conversationalists, neuroscientists at Dartmouth College have taken that idea and carried it to new places. As part of a series of studies on how two minds meet in real life, they reported surprising findings on the interplay of eye contact and the synchronization of neural activity between two people during conversation. In a paper published on September 14 in Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences USA, the researchers suggest that being in tune with a conversational partner is good but that

What is found in a good conversation? It is certainly correct to say words—the more engagingly put, the better. But conversation also includes “eyes, smiles, the silences between the words,” as the Swedish author Annika Thor wrote. It is when those elements hum along together that we feel most deeply engaged with, and most connected to, our conversational partner, as if we are in sync with them. Like good conversationalists, neuroscientists at Dartmouth College have taken that idea and carried it to new places. As part of a series of studies on how two minds meet in real life, they reported surprising findings on the interplay of eye contact and the synchronization of neural activity between two people during conversation. In a paper published on September 14 in Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences USA, the researchers suggest that being in tune with a conversational partner is good but that