Micah L. Sifry in The New Republic:

Micah L. Sifry in The New Republic:

Ten years ago today, on September 17, 2011, a small band of anarchists, artists, and anti-poverty organizers convened themselves in Zuccotti Park in downtown Manhattan, steps from the New York Stock Exchange. They were there to challenge the power of Wall Street and also to try something new in the annals of modern American protest movements: to be a democratic assembly of all who wanted to participate in deciding how and what they would do next. On their first night together that Saturday, perhaps 100 or 200 at best camped out under the park’s 55 honey locust trees.

At first, they were tolerated by the police, since they had stumbled by good fortune into a safe harbor—a privately owned public park that legally allowed people to remain there 24 hours a day. And they were ignored, or derided, by the media, which had seen many Wall Street protests come and go. Over the next few days, their numbers grew modestly while they established working groups for everything from food and health care to a people’s library and scrambled to spread their own messages through the internet. Five days after the Zuccotti occupation began, a nearby protest against the execution of Troy Davis, a Black man in Georgia, brought hundreds of new and somewhat more diverse faces down to the plaza. But it wasn’t until the next Saturday, when the police attacked a column of marchers and one white-shirted deputy was caught on video viciously pepper-spraying a group of women who were already detained, that support for Occupy in New York started to surge.

More here.

Mariana Mazzucato, Rainer Kattel, and Josh Ryan-Collins over at Boston Review:

Mariana Mazzucato, Rainer Kattel, and Josh Ryan-Collins over at Boston Review:

I

I “The world had enough novels,”

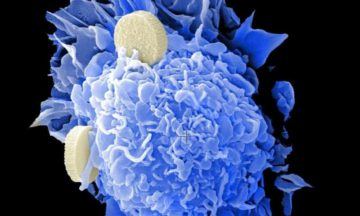

“The world had enough novels,”  A team of researchers with biotechnology corporation Genentech Inc., has developed a new way to capture the origins and early adaptive processes that are involved in therapy responses to cancer treatments. In their paper published in the journal Nature Biotechnology, the group describes how their new system can be used to help treat resistant types of cancer.

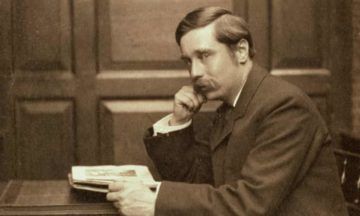

A team of researchers with biotechnology corporation Genentech Inc., has developed a new way to capture the origins and early adaptive processes that are involved in therapy responses to cancer treatments. In their paper published in the journal Nature Biotechnology, the group describes how their new system can be used to help treat resistant types of cancer. In his writings, Wells conveyed a plethora of futuristic prophecies, from space travel to genetic engineering, from the atomic bomb to the world wide web. There was no other fiction writer who saw into the future of humankind as clearly and boldly as he did.

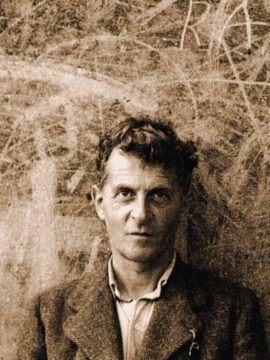

In his writings, Wells conveyed a plethora of futuristic prophecies, from space travel to genetic engineering, from the atomic bomb to the world wide web. There was no other fiction writer who saw into the future of humankind as clearly and boldly as he did. In 1920, after failing five times to find a publisher for his newly finished book, Tractatus Logico Philosophicus, the Austrian-born philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein consoled himself in a letter to Bertrand Russell:

In 1920, after failing five times to find a publisher for his newly finished book, Tractatus Logico Philosophicus, the Austrian-born philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein consoled himself in a letter to Bertrand Russell:

Between June 2020 and February 2021, the iPhones of nine Bahraini activists – including two dissidents exiled in London and three members of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights – were hacked using the Pegasus spyware that was developed by NSO Group, an Israeli cyber-surveillance firm regulated by Israel’s defence ministry.

Between June 2020 and February 2021, the iPhones of nine Bahraini activists – including two dissidents exiled in London and three members of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights – were hacked using the Pegasus spyware that was developed by NSO Group, an Israeli cyber-surveillance firm regulated by Israel’s defence ministry. In the 1770s, the Paduan philosopher, natural historian, and Augustinian abbot Alberto Fortis (1741–1803) undertook several journeys to the other side of Adriatic, one of them to the lands of the Morlacchi. His travels were memorialized as Viaggio in Dalmazia, an epistolary travelogue printed in Venice in 1774 and translated into German two years later. It inspired Goethe to retranslate a folk poem collected by Fortis for his book and to recommend it for inclusion in Herder’s collection of Volkslieder. Goethe’s translation, initially published anonymously, made the “Xalostna pjesanca plemenite Asan-Aghinize” one of the most famous folkloric artifacts of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Europe.

In the 1770s, the Paduan philosopher, natural historian, and Augustinian abbot Alberto Fortis (1741–1803) undertook several journeys to the other side of Adriatic, one of them to the lands of the Morlacchi. His travels were memorialized as Viaggio in Dalmazia, an epistolary travelogue printed in Venice in 1774 and translated into German two years later. It inspired Goethe to retranslate a folk poem collected by Fortis for his book and to recommend it for inclusion in Herder’s collection of Volkslieder. Goethe’s translation, initially published anonymously, made the “Xalostna pjesanca plemenite Asan-Aghinize” one of the most famous folkloric artifacts of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Europe. By most reasonable metrics, the 2017 indie adventure game Night In the Woods is not a horror game. There are no jump scares, no dread-inducing meta experiments, no resource scarcity (no item management to speak of, actually), and no tense gameplay sequences. Night In the Woods is a story about a 20-year-old cat named Mae Borowski who has returned to her hometown of Possum Springs after deciding to drop out of college, and you spend the majority of the game exploring her relationships with the townsfolk—with her neighbors, with her parents, with the friends she left behind. Aside from a few rhythm game inspired musical sequences, it is a relatively quiet game that thrives on rich dialogue and character interactions.

By most reasonable metrics, the 2017 indie adventure game Night In the Woods is not a horror game. There are no jump scares, no dread-inducing meta experiments, no resource scarcity (no item management to speak of, actually), and no tense gameplay sequences. Night In the Woods is a story about a 20-year-old cat named Mae Borowski who has returned to her hometown of Possum Springs after deciding to drop out of college, and you spend the majority of the game exploring her relationships with the townsfolk—with her neighbors, with her parents, with the friends she left behind. Aside from a few rhythm game inspired musical sequences, it is a relatively quiet game that thrives on rich dialogue and character interactions. Allow me to introduce Tom. You’ll like him. Tom is handsome and sleek, with a discreet dress sense and all the social graces, but what really counts is that he’s kind. You can’t beat kindness. He won’t bug you or bore you, and so exactly will he meet your needs, whatever they are, that it’s as if he understood, in advance, what they were going to be. And did I mention that he knows a lot? As in, everything? To sum up, Tom is quite a guy. If you want to be picky, or downright rude, you could point out that he’s a robot, but hey: nobody’s perfect.

Allow me to introduce Tom. You’ll like him. Tom is handsome and sleek, with a discreet dress sense and all the social graces, but what really counts is that he’s kind. You can’t beat kindness. He won’t bug you or bore you, and so exactly will he meet your needs, whatever they are, that it’s as if he understood, in advance, what they were going to be. And did I mention that he knows a lot? As in, everything? To sum up, Tom is quite a guy. If you want to be picky, or downright rude, you could point out that he’s a robot, but hey: nobody’s perfect.