Category: Archives

The next frontier for human embryo research

Elizabeth Svoboda in Nature:

In a laboratory in Israel, an incubator drum spins on a bench. The two glass bottles attached to the drum contain mouse embryos, each the size of a grain of rice, with translucent, pulsing hearts.

In a laboratory in Israel, an incubator drum spins on a bench. The two glass bottles attached to the drum contain mouse embryos, each the size of a grain of rice, with translucent, pulsing hearts.

Whole mouse embryos have typically been grown in vitro for only about 24 hours. But by carefully tuning the mix of chemicals that the mouse embryos are bathed in, a team at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, managed to sustain five-day-old embryos outside the uterus for six more days1. This is about one-third of their normal three-week gestation and parallels some events in the first trimester of human embryonic development. Growing human embryos using similar techniques could allow scientists to study processes integral to human development that have long been hidden from view. “This may become the gold standard of looking at human embryonic biology,” says Jacob Hanna, a stem-cell biologist and lead researcher on the project at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

This and other recent breakthroughs, such as the creation of human-embryo-like structures from pluripotent stem cells, give scientists an arsenal of tools with which to probe further into early human development. Hanna’s drum incubator and these human-embryo models promise to allow more detailed study of processes such as gastrulation — in which three germ-cell layers develop into an array of tissues — and organ formation. Hanna and others say that understanding these crucial embryonic phases is essential to devising therapies that correct developmental errors, as well as to creating transplantable human organs.

More here.

Republicans would “rather end democracy” than turn away from Trump, says Harvard professor

Dear Obeidallah in Salon:

It can happen here. The “it” ought to be obvious by now: an authoritarian or even fascist regime in the United States. That was a big reason why Harvard professor Steven Levitsky, along with his colleague Daniel Ziblatt, published the 2018 book “How Democracies Die.” They wanted to warn Americans of the dangerous signs they saw in Donald Trump’s presidency that followed the authoritarian playbook.

It can happen here. The “it” ought to be obvious by now: an authoritarian or even fascist regime in the United States. That was a big reason why Harvard professor Steven Levitsky, along with his colleague Daniel Ziblatt, published the 2018 book “How Democracies Die.” They wanted to warn Americans of the dangerous signs they saw in Donald Trump’s presidency that followed the authoritarian playbook.

So where are we now in terms of our democracy? I spoke with Levitsky recently for Salon Talks, and here’s one line that really stood out: Levitsky told me, “Five years ago I would have laughed you out of the room if you suggested our democracy could die.” But today, he added, we see the Republican Party apparently focused on breaking our democracy. In a nutshell, Levitsky believes the threat to our democracy is more acute today than when Trump was in the White House, since the GOP is desperate to retain its fading power in the face of hostile demographic change.

Levitsky describes today’s GOP as “clearly an authoritarian party.” Worse yet, it’s no longer all about Trump. He sees the GOP continuing on its anti-democratic path for years to come, saying that even the contested term “fascist” is becoming more defensible given the GOP’s defense or denial of the Jan. 6 Capitol attack.

More here.

Sunday, October 17, 2021

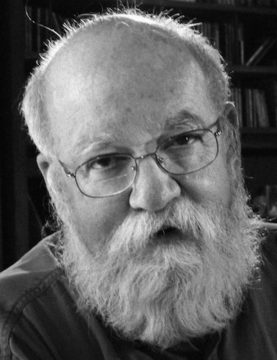

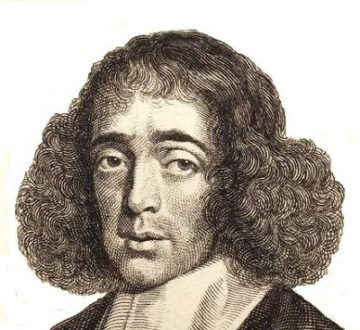

Dennett and Spinoza

Walter Veit in the Australasian Philosophical Review:

Genevieve Lloyd has done much to promote serious engagement with Baruch Spinoza and has demonstrated many ways in which Spinoza can inform and challenge current debates in the philosophical mainstream. In her article in this issue, Lloyd invites us to challenge the simplistic caricature of Spinoza as a paradigm ‘rationalist’, thus providing us with rich insights into the subtleties of Spinoza’s naturalist view on minds, knowledge, and reason. This more accurate picture, however, offers a striking similarity to the work of Daniel Dennett. Indeed, Spinoza and Dennett are alike in sharing their fervent opposition to Descartes’ conception of mind and body.

Genevieve Lloyd has done much to promote serious engagement with Baruch Spinoza and has demonstrated many ways in which Spinoza can inform and challenge current debates in the philosophical mainstream. In her article in this issue, Lloyd invites us to challenge the simplistic caricature of Spinoza as a paradigm ‘rationalist’, thus providing us with rich insights into the subtleties of Spinoza’s naturalist view on minds, knowledge, and reason. This more accurate picture, however, offers a striking similarity to the work of Daniel Dennett. Indeed, Spinoza and Dennett are alike in sharing their fervent opposition to Descartes’ conception of mind and body.

Lloyd [2021] herself alludes to Dennett when she suggests that a serious engagement with Spinoza might allow us to provide an alternative framing of the problem of consciousness—one that replaces the current metaphors with what Dennett [1991: 455] would describe as novel ‘tools of thought’. While Lloyd [2017] has addressed the connection between Spinoza and the problem of consciousness in a previous publication, little has been made of the connection between these two Anti-Cartesian conceptions of the mind.

Lloyd [2021] herself alludes to Dennett when she suggests that a serious engagement with Spinoza might allow us to provide an alternative framing of the problem of consciousness—one that replaces the current metaphors with what Dennett [1991: 455] would describe as novel ‘tools of thought’. While Lloyd [2017] has addressed the connection between Spinoza and the problem of consciousness in a previous publication, little has been made of the connection between these two Anti-Cartesian conceptions of the mind.

More here.

Harvard psychologist Joshua Greene explains Facebooks’s trolley problem

Colleen Walsh in The Harvard Gazette:

Testimony by former Facebook employee Frances Haugen, who holds a degree from Harvard Business School, and a series in the Wall Street Journal have left many, including Joshua Greene, Harvard professor of psychology, calling for stricter regulation of the social media company. Greene, who studies moral judgment and decision-making and is the author of “Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them,” says Facebook executives’ moral emotions are not well-tuned to the consequences of their decisions, a common human frailty that can lead to serious social harms. Among other things, the company has been accused of stoking division through the use of algorithms that promote polarizing content and ignoring the toxic effect its Instagram app has on teenage girls. In an interview with the Gazette, Greene discussed how his work on moral dilemmas can be applied to Facebook. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Testimony by former Facebook employee Frances Haugen, who holds a degree from Harvard Business School, and a series in the Wall Street Journal have left many, including Joshua Greene, Harvard professor of psychology, calling for stricter regulation of the social media company. Greene, who studies moral judgment and decision-making and is the author of “Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them,” says Facebook executives’ moral emotions are not well-tuned to the consequences of their decisions, a common human frailty that can lead to serious social harms. Among other things, the company has been accused of stoking division through the use of algorithms that promote polarizing content and ignoring the toxic effect its Instagram app has on teenage girls. In an interview with the Gazette, Greene discussed how his work on moral dilemmas can be applied to Facebook. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

More here.

The Strange Death of Conservative America

J. Bradford DeLong in Project Syndicate:

If you are concerned about the well-being of the United States and interested in what the country could do to help itself, stop what you are doing and read historian Geoffrey Kabaservice’s superb 2012 book, Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, from Eisenhower to the Tea Party. To understand why, allow me a brief historical interlude.

If you are concerned about the well-being of the United States and interested in what the country could do to help itself, stop what you are doing and read historian Geoffrey Kabaservice’s superb 2012 book, Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, from Eisenhower to the Tea Party. To understand why, allow me a brief historical interlude.

Until roughly the start of the seventeenth century, people generally had to look back in time to find evidence of human greatness. Humanity had reached its peak in long lost golden ages of demigods, great thinkers, and massive construction projects. When people did look to the future for promise of a better world, it was a religious vision they conjured – a city of God, not of man. When they looked to their own society, they saw that it was mostly the same as in the past, with Henry VIII and his retinue holding court in much the same fashion as Agamemnon, or Tiberius Caesar, or Arthur.

But then, around 1600, people in Western Europe noticed that history was moving largely in one particular direction, owing to the expansion of humankind’s technological capabilities.

More here.

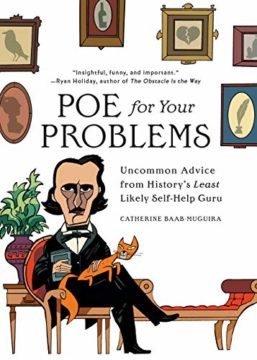

The Millions Interviews Catherine Baab-Muguira

Benjamin Morris in The Millions:

“Live your best life.” It’s one of the most common, yet worthless, aphorisms offered today. Chipper, insipid, and surprisingly relativistic (it fits arsonists as well as anybody), this meaningless maxim is the Tic-Tac of modern aspiration, boasting all the nuance and depth of Target word-art or pastel Instagram posts. Fed up with such drivel, and equally skeptical of the therapy-industrial complex, writer Catherine Baab-Muguira urges us in her debut book of nonfiction to take the exact opposite tack: to live our worst life instead.

“Live your best life.” It’s one of the most common, yet worthless, aphorisms offered today. Chipper, insipid, and surprisingly relativistic (it fits arsonists as well as anybody), this meaningless maxim is the Tic-Tac of modern aspiration, boasting all the nuance and depth of Target word-art or pastel Instagram posts. Fed up with such drivel, and equally skeptical of the therapy-industrial complex, writer Catherine Baab-Muguira urges us in her debut book of nonfiction to take the exact opposite tack: to live our worst life instead.

In Poe for Your Problems: Uncommon Advice from History’s Least Likely Self-Help Guru (Running Press), Baab-Muguira preaches the good news of one of the greatest screw-ups of all time: Edgar Allan Poe. Drawing insights on work, love, ambition, and legacy from Poe’s blazing dumpster fire of a life, she concludes that the surest way to thrive is to sabotage everything you can get your mitts on, then build something new and totally novel out of the wreckage. Her literary forebears—Richard Fariña and Charles Bukowski among others—would be proud.

Recently I posed Baab-Muguira a few questions for The Millions, which she graciously answered amid her publicity tour of Richmond pubs—knocking back local spirits in honor of her favorite local spirit.

More here.

Myriam Sarachik (1933 – 2021) physicist

Sunday Poem

The Second Coming

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Paddy Moloney (1938 – 2021) musician

Roberto Roena (1940 – 2021) percussionist

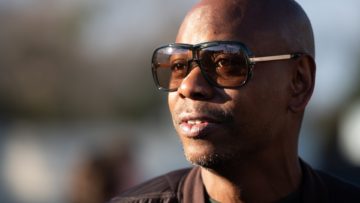

Dave Chappelle’s show is a rip-off

Damian Reilly in The Spectator:

Towards what seemed like the halfway point of his show in London last night, Dave Chappelle announced to the crowd he was going to tell us something he was refusing to tell the media. He wanted us to know, he said while looking sadly at the floor, that his quarrel was not with the gay or the trans communities . No, no. Looking up and raising an index finger, he explained: ‘I’m fighting a corporate agenda that needs to be addressed.’ Thinking we still had another hour of the show to go, we cheered. ‘You fight those corporate vampires, Dave!’ we thought. He then let us know, whenever it was possible, that we should be kind to one another. Very shortly after that he raised his thumbs aloft and walked off stage: 45 minutes. Friday night tickets are £160. You show those corporate vamp… oh.

Towards what seemed like the halfway point of his show in London last night, Dave Chappelle announced to the crowd he was going to tell us something he was refusing to tell the media. He wanted us to know, he said while looking sadly at the floor, that his quarrel was not with the gay or the trans communities . No, no. Looking up and raising an index finger, he explained: ‘I’m fighting a corporate agenda that needs to be addressed.’ Thinking we still had another hour of the show to go, we cheered. ‘You fight those corporate vampires, Dave!’ we thought. He then let us know, whenever it was possible, that we should be kind to one another. Very shortly after that he raised his thumbs aloft and walked off stage: 45 minutes. Friday night tickets are £160. You show those corporate vamp… oh.

Dave Chappelle is a very rich man. Reading through the coverage of the whirligig of controversy he quite deliberately tipped off last week by finishing his latest Netflix special The Closer with the observation that (to paraphrase) ‘trans pussy is not the same as non-trans pussy’, the thing that really stood out was how much he is paid to do those specials. Since 2017, he’s done six – each about 70 minutes long. Netflix reportedly pays him $20 million per show.

At last night’s show in Hammersmith (3,500 seats, so about $3.5 million for 8 nights – or six hours on stage, all in), Chappelle seemed keen to let us know he was richer than us. He told a joke at the outset that involved the detail he’d reached 60 miles an hour in his car on his driveway, in pursuit of a malefactor. ‘That probably seems pretty fast for a driveway,’ he said. ‘But that’s because you’re thinking of your own house.’ Repeatedly, too, he bought his bodyguards out from the wings so we could see them for ourselves.

I’d warned my wife on the way in she would probably hate every second of it. I thought she’d be appalled by much of his humour. But the show was funny. It wasn’t as subversive or anything like as provocative as The Closer, but he still had her and the rest of the audience roaring through a lengthy section on male-on-male rape. Chappelle is very good at what he does. In The Closer, he unironically references the Greatest of All Time status some have bestowed on him, which is a considerable stretch – particularly on last night’s showing. But is he the hero we need? Certainly, comedy now seems the only force capable of making meaningful inroads against the unsmiling, dark armies of cancel culture and corporate-backed wokery. It’s only the comics who are allowed to say what is increasingly deemed unsayable for the rest of us.

More here.

Saturday, October 16, 2021

How Emerging Markets Hurt Poor Countries

C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh in Boston Review ( Image: James Robertson/Jubilee Debt Campaign):

C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh in Boston Review ( Image: James Robertson/Jubilee Debt Campaign):

It is by now well known that three decades of financial globalization have led to massive increases in income and asset inequalities in the United States and Europe. But in the developing world, the effects of financial globalization have been even worse: along with new inequality and instability, the creation of “emerging markets” to support investment in poor countries has undermined development projects and created a relationship in which poor countries supply financial resources to rich ones. This is exactly the opposite of what was meant to happen. Yet this growing disparity in per capita incomes across the global North and South is not a bug in the system but a result of how global financial markets have been allowed to function.

The biggest promise of neoliberal finance, initially pushed by economists such as Ronald McKinnon from the late 1970s onward, was that it would enable greater and more secure access to resources for development for countries deemed too poor to generate enough savings within their own economies to fund necessary investment. To access savings from abroad, they were encouraged to tap into global financial markets.

At the same time, changes in the economies of the developed world in the late 1980s generated mobile finance willing to slosh around the globe in search of higher returns. Deregulation enabled new financial “instruments,” such as credit default swaps (which supposedly insure against debt default) and other derivatives, that suddenly made it attractive to provide finance to activities and borrowers that were previously excluded. In the United States this gave rise to the phenomenon of “sub-prime” lending in the housing market, but it also encouraged international finance to provide loans to countries without much previous access to private funds. Indeed, many lenders actively sought out new borrowers, as moving capital was one of the major routes to higher profitability in the financial sector.

These developments gave rise to the term “emerging markets,” first used by economists at the World Bank’s private investment arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in 1981 to promote mutual fund investments in developing countries.

More here.

‘Ted Lasso’ is not about what you think

David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele over at CNN:

David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele over at CNN:

The breakout show of the pandemic has been Apple+’s “Ted Lasso,” now just finished with its second season. The titular character, an American college football coach who improbably finds himself coaching the fictional English football club AFC Richmond, seems to exude kindness and optimism. He comes across as a folksy rube at the beginning — the worst kind of stereotype of Americans abroad — but during the first season manages to win just about everyone over to his side even in the face of betrayal and disaster. The second season seemed to continue this trajectory, as Ted and those around him confront their inner demons.

The disastrous voyage of Satoshi, the world’s first cryptocurrency cruise ship

Sophie Elmhirst in The Guardian (Illustration by Pete Reynolds):

Sophie Elmhirst in The Guardian (Illustration by Pete Reynolds):

On the evening of 7 December 2010, in a hushed San Francisco auditorium, former Google engineer Patri Friedman sketched out the future of humanity. The event was hosted by the Thiel Foundation, established four years earlier by the arch-libertarian PayPal founder Peter Thiel to “defend and promote freedom in all its dimensions”. From behind a large lectern, Friedman – grandson of Milton Friedman, one of the most influential free-market economists of the last century – laid out his plan. He wanted to transform how and where we live, to abandon life on land and all our decrepit assumptions about the nature of society. He wanted, quite simply, to start a new city in the middle of the ocean.

Friedman called it seasteading: “Homesteading the high seas,” a phrase borrowed from Wayne Gramlich, a software engineer with whom he’d founded the Seasteading Institute in 2008, helped by a $500,000 donation from Thiel. In a four-minute vision-dump, Friedman explained his rationale. Why, he asked, in one of the most advanced countries in the world, were they still using systems of government from 1787? (“If you drove a car from 1787, it would be a horse,” he pointed out.) Government, he believed, needed an upgrade, like a software update for a phone. “Let’s think of government as an industry, where countries are firms and citizens are customers!” he declared.

More here.

An Intro to Feminist Economics

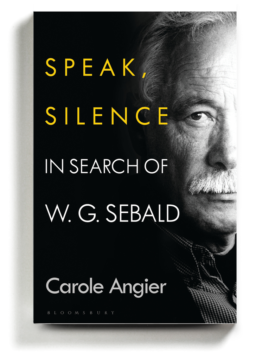

A Biography of W.G. Sebald

Dwight Garner at the NYT:

W.G. Sebald is probably the most revered German writer of the second half of the 20th century. His best-known books — “The Emigrants,” “The Rings of Saturn,” “Austerlitz,” published here between 1997 and 2001 — are famously difficult to categorize.

W.G. Sebald is probably the most revered German writer of the second half of the 20th century. His best-known books — “The Emigrants,” “The Rings of Saturn,” “Austerlitz,” published here between 1997 and 2001 — are famously difficult to categorize.

Carole Angier, the author of a new biography, “Speak, Silence: In Search of W.G. Sebald,” likes to refer to them, borrowing from the writer Michael Hamburger, as “essayistic semi-fiction.” I prefer a comment from one of Sebald’s students, who said that his otherworldly sentences resemble “how the dead would write.”

His themes — the burden of the Holocaust, the abattoir-like crush of history in general, the end of nature, the importance of solitude and silence — are sifted into despairing books that can resemble travel writing of an existential sort.

more here.

Why Middlemarch Still Matters

Johanna Thomas-Corr at The New Statesman:

Eliot’s humanism tends to inspire awe in her readers. “She seems to care for people, indiscriminately and in their entirety, as it was once said God did,” wrote Zadie Smith in a 2008 essay on Middlemarch. As it was once said God did. My first thought is of Middlemarch’s omniscient narrator: sage, a little sarcastic, a little judgemental as she tunes into the thoughts of each character, catching them in the act of realising something about themselves.

Eliot’s humanism tends to inspire awe in her readers. “She seems to care for people, indiscriminately and in their entirety, as it was once said God did,” wrote Zadie Smith in a 2008 essay on Middlemarch. As it was once said God did. My first thought is of Middlemarch’s omniscient narrator: sage, a little sarcastic, a little judgemental as she tunes into the thoughts of each character, catching them in the act of realising something about themselves.

But when Smith talks about Eliot being like God, what she means is that Eliot was “so alive to the mass of existence” that she conferred as much attention on her mediocre characters as she did on her more admirable ones. Smith’s essay is a sort of riposte to Henry James’s 1873 review of Middlemarch, in which he argued that Eliot should have focused her energies on Dorothea, who “exhales a sort of aroma of spiritual sweetness”, rather than lingering so long on the feckless horse-trading Fred Vincy, “with his somewhat meagre tribulations and his rather neutral egotism”.

more here.

Launch of NASA’s Lucy Mission To Jupiter’s Trojan Asteroids

The Trump Presidency Is Still an Active Crime Scene

Susan Glasser in The New Yorker:

Every Administration produces a shelf full of memoirs, of the score-settling variety and otherwise. The first known White House chronicle by someone other than a President came from Paul Jennings, an enslaved person whose memoir of President James Madison’s White House was published in 1865. In modern times, Bill Clinton’s two terms gave us Robert Reich’s “Locked in the Cabinet,” perhaps the best recent exposé of that most feckless of Washington jobs, and George Stephanopoulos’s “All Too Human,” a memorable account of a political wunderkind that was honest—too honest, at times, to suit his patron—about what it was really like backstage at the Clinton White House. George W. Bush’s Presidency, with its momentous years of war and terrorism, produced memoirs, many of them quite good, from multiple deputy speechwriters, a deputy national-security adviser, a deputy director of the Office of Public Liaison, and even a deputy director of the White House Office of Faith-Based Initiatives. President Obama’s White House stenographer wrote a memoir, as did his photographer, his deputy White House chief of staff, his campaign strategists, a deputy national-security adviser, a deputy speechwriter, and even one of the junior press wranglers whose job it was to oversee the White House press pool.

Every Administration produces a shelf full of memoirs, of the score-settling variety and otherwise. The first known White House chronicle by someone other than a President came from Paul Jennings, an enslaved person whose memoir of President James Madison’s White House was published in 1865. In modern times, Bill Clinton’s two terms gave us Robert Reich’s “Locked in the Cabinet,” perhaps the best recent exposé of that most feckless of Washington jobs, and George Stephanopoulos’s “All Too Human,” a memorable account of a political wunderkind that was honest—too honest, at times, to suit his patron—about what it was really like backstage at the Clinton White House. George W. Bush’s Presidency, with its momentous years of war and terrorism, produced memoirs, many of them quite good, from multiple deputy speechwriters, a deputy national-security adviser, a deputy director of the Office of Public Liaison, and even a deputy director of the White House Office of Faith-Based Initiatives. President Obama’s White House stenographer wrote a memoir, as did his photographer, his deputy White House chief of staff, his campaign strategists, a deputy national-security adviser, a deputy speechwriter, and even one of the junior press wranglers whose job it was to oversee the White House press pool.

There’s a few golden nuggets to be mined even from the most unreadable, obscure, and self-serving of such memoirs. Even before it ended, the Trump Administration produced a remarkable number of these accounts, as wave after wave of fired press secretaries, ousted Cabinet officials, and disgruntled former aides signed lucrative book deals. There were so many books seeking to explain Trump and his times that the book critic of the Washington Post wrote his own book about all of the books. Trump’s fired executive assistant—ousted because she claimed, at a boozy dinner with reporters, that the President had said nasty things about his daughter Tiffany—wrote a book. Trump’s first two press secretaries wrote books. First Lady Melania Trump’s former best friend wrote a book. Trump’s third national-security adviser, John Bolton, wrote an explosive book with direct-from-the-Situation-Room allegations of Presidential malfeasance that might have turned the tide in Trump’s first impeachment trial had Bolton actually testified in it. And none of those even covered the epic, Presidency-ending year of 2020.

Dozens of books have now been published or are in the works which address the covid pandemic, the 2020 Presidential election, and the violent final days of Trump’s tenure. The history of the Trump Presidency that I am writing with my husband, Peter Baker, of the Times, already has eighty-nine books in its bibliography; many are excellent reported works by journalists, in addition to the first-person recollections, such as they are, by those who worked with and for Trump. This month, Stephanie Grisham became the third former Trump Administration press secretary to publish her account. Grisham, who has the distinction of being the only White House press secretary never to actually hold a press briefing, has written a tell-all that includes such details as the President calling her from Air Force One to discuss his genitalia.

More here.