Declan Ryan at Poetry Magazine:

“Many of his poems are at best rococo vases of an eighteenth century artificiality, insisted on in our strenuous age though thrones go toppling down.” Such was Harriet Monroe’s verdict on the British writer Walter de la Mare in a review she wrote for Poetry in 1919. Her appraisal echoed several persistent criticisms of de la Mare’s poems: the frequent use of inversion, the decorated lexicon, the never-fashionable attempt to paint a sort of Elfland, and the clinging to the primacy of childhood.

“Many of his poems are at best rococo vases of an eighteenth century artificiality, insisted on in our strenuous age though thrones go toppling down.” Such was Harriet Monroe’s verdict on the British writer Walter de la Mare in a review she wrote for Poetry in 1919. Her appraisal echoed several persistent criticisms of de la Mare’s poems: the frequent use of inversion, the decorated lexicon, the never-fashionable attempt to paint a sort of Elfland, and the clinging to the primacy of childhood.

That said, from the time when de la Mare first came to widespread public attention, via his collections The Listeners (1912) and Peacock Pie (1913) and the hugely popular Georgian Poetry anthologies, of which he was a staple, he grew into a lauded—if always defiantly eccentric—figure. He was celebrated by some of the leading (and most skeptical) poets and critics of his era, such as Edward Thomas and Robert Frost.

more here.

I

I While it can sometimes seem like humanity is hell-bent on environmental destruction, it’s unlikely our actions will end all life on Earth. Some creatures are sure to endure in this

While it can sometimes seem like humanity is hell-bent on environmental destruction, it’s unlikely our actions will end all life on Earth. Some creatures are sure to endure in this  T

T Czesław Miłosz, one of the greatest poets and thinkers of the past hundred years, is not generally considered a Californian. But the Polish-Lithuanian Nobel laureate spent four decades in Berkeley—more time than any other single place he lived. His debut collection in America, a short Selected Poems in 1973, was published by a small New York house, Seabury Press. Introduced by Kenneth Rexroth, the collection of about fifty poems included many from Ocalenie, the book that had appeared in Warsaw in 1945.

Czesław Miłosz, one of the greatest poets and thinkers of the past hundred years, is not generally considered a Californian. But the Polish-Lithuanian Nobel laureate spent four decades in Berkeley—more time than any other single place he lived. His debut collection in America, a short Selected Poems in 1973, was published by a small New York house, Seabury Press. Introduced by Kenneth Rexroth, the collection of about fifty poems included many from Ocalenie, the book that had appeared in Warsaw in 1945. Tickled by sunlight, life teems at the ocean surface. Yet the influence of any given microbe, plankton, or fish there extends far beyond this upper layer. In the form of dead organisms or poop, organic matter rains thousands of feet down onto the seafloor, nourishing ecosystems, influencing delicate ocean chemistry, and sequestering carbon in the deep sea.

Tickled by sunlight, life teems at the ocean surface. Yet the influence of any given microbe, plankton, or fish there extends far beyond this upper layer. In the form of dead organisms or poop, organic matter rains thousands of feet down onto the seafloor, nourishing ecosystems, influencing delicate ocean chemistry, and sequestering carbon in the deep sea. It’s not surprising that the narrative we’ve heard a lot lately is that such theories exploded over the past 18 months. It’s common to see headlines

It’s not surprising that the narrative we’ve heard a lot lately is that such theories exploded over the past 18 months. It’s common to see headlines On July 8, 1962, just after 11 pm, the sky over Hawaii turned, in a moment, from black to blazing. Streetlights went out, all at once; radios stopped working. For several minutes, a red orb, edged in purple, surrounding a luminous yellow core, made the night as bright as day. It then dimmed, slowly, receding into color-changing auroras. When these lights faded, they left behind a spectral glow that persisted for hours and could be seen throughout the Pacific.

On July 8, 1962, just after 11 pm, the sky over Hawaii turned, in a moment, from black to blazing. Streetlights went out, all at once; radios stopped working. For several minutes, a red orb, edged in purple, surrounding a luminous yellow core, made the night as bright as day. It then dimmed, slowly, receding into color-changing auroras. When these lights faded, they left behind a spectral glow that persisted for hours and could be seen throughout the Pacific.

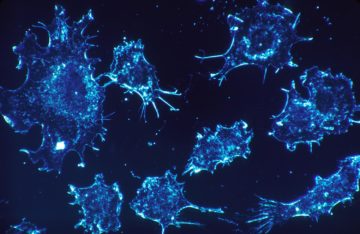

Immunotherapy is a promising strategy to treat cancer by stimulating the body’s own immune system to destroy tumor cells, but it only works for a handful of cancers. MIT researchers have now discovered a new way to jump-start the immune system to attack tumors, which they hope could allow immunotherapy to be used against more types of cancer.

Immunotherapy is a promising strategy to treat cancer by stimulating the body’s own immune system to destroy tumor cells, but it only works for a handful of cancers. MIT researchers have now discovered a new way to jump-start the immune system to attack tumors, which they hope could allow immunotherapy to be used against more types of cancer. Teaching writing, unlike most other kinds of teaching, is an intervention, closer to therapy than to any transmissible instruction. But with all the fussing about craft — anyone who teaches has a personal punch-list — we almost never hear about or get close to the real business, the meld. Maybe because each teacher is different and each interaction draws on a unique set of human variables.

Teaching writing, unlike most other kinds of teaching, is an intervention, closer to therapy than to any transmissible instruction. But with all the fussing about craft — anyone who teaches has a personal punch-list — we almost never hear about or get close to the real business, the meld. Maybe because each teacher is different and each interaction draws on a unique set of human variables. In an increasingly data-driven world, mathematical tools known as wavelets have become an indispensable way to analyze and understand information. Many researchers receive their data in the form of continuous signals, meaning an unbroken stream of information evolving over time, such as a geophysicist listening to sound waves bouncing off of rock layers underground, or a data scientist studying the electrical data streams obtained by scanning images. These data can take on many different shapes and patterns, making it hard to analyze them as a whole or to take them apart and study their pieces — but wavelets can help.

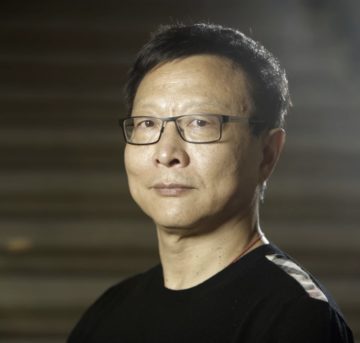

In an increasingly data-driven world, mathematical tools known as wavelets have become an indispensable way to analyze and understand information. Many researchers receive their data in the form of continuous signals, meaning an unbroken stream of information evolving over time, such as a geophysicist listening to sound waves bouncing off of rock layers underground, or a data scientist studying the electrical data streams obtained by scanning images. These data can take on many different shapes and patterns, making it hard to analyze them as a whole or to take them apart and study their pieces — but wavelets can help. Sheng, a professor of composition at the University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theater, and Dance, said he was sorry for showing a 1965 film version of Othello, starring Laurence Olivier in blackface, during an undergraduate class last month. In the first apology, sent to students shortly after the class ended, he called the film’s use of blackface “racially insensitive and outdated” and wrote that it was “wrong for me” to show it. He promised they would discuss the issue in the next class. As it turns out, he wouldn’t get that chance.

Sheng, a professor of composition at the University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theater, and Dance, said he was sorry for showing a 1965 film version of Othello, starring Laurence Olivier in blackface, during an undergraduate class last month. In the first apology, sent to students shortly after the class ended, he called the film’s use of blackface “racially insensitive and outdated” and wrote that it was “wrong for me” to show it. He promised they would discuss the issue in the next class. As it turns out, he wouldn’t get that chance. Yet the fact remains that

Yet the fact remains that  The wager made by Atkins is that if reality can be derealized by such technologies, it might also be rediscovered there, and this might occur in a few ways. First, he believes that, once outmoded, technology passes over to the side of “base materiality”; its very clunkiness becomes a reality effect. Atkins adapts the term corpsing—the moment when an actor breaks character and so dispels the illusion of the performance—“to describe a kind of structural revelation more generally”; his examples are when a vinyl record jumps or a streaming movie buffers. To corpse a medium is to expose its materiality, even to underscore its mortality, and in this moment the real might poke through. Second, punctuated by the gestural tics of the Atkins avatar, The Worm is also rife with manufactured glitches—sudden blurs, flares, beeps, and crackles—and these apparent cracks in the artifice might provide another opening to the real. Although these reality effects are artificial, “they baffle the signs of reality by parodying them, engendering a new kind of realism.”7 Third, if the real might be felt when an illusion fails, so too might it be sensed when that illusion is “glazed with effects to italicize the artifice,” that is, when illusionism is pushed to a hyperreal point.

The wager made by Atkins is that if reality can be derealized by such technologies, it might also be rediscovered there, and this might occur in a few ways. First, he believes that, once outmoded, technology passes over to the side of “base materiality”; its very clunkiness becomes a reality effect. Atkins adapts the term corpsing—the moment when an actor breaks character and so dispels the illusion of the performance—“to describe a kind of structural revelation more generally”; his examples are when a vinyl record jumps or a streaming movie buffers. To corpse a medium is to expose its materiality, even to underscore its mortality, and in this moment the real might poke through. Second, punctuated by the gestural tics of the Atkins avatar, The Worm is also rife with manufactured glitches—sudden blurs, flares, beeps, and crackles—and these apparent cracks in the artifice might provide another opening to the real. Although these reality effects are artificial, “they baffle the signs of reality by parodying them, engendering a new kind of realism.”7 Third, if the real might be felt when an illusion fails, so too might it be sensed when that illusion is “glazed with effects to italicize the artifice,” that is, when illusionism is pushed to a hyperreal point.