Yulia Gromova interviews Quinn Slobodian in Strelka:

Yulia Gromova interviews Quinn Slobodian in Strelka:

Yulia Gromova: The founding fathers of neoliberalism—Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, and others, as you describe in your book, have created the basis for today’s global world order. They laid the foundation for institutions including the European Union and the World Trade Organization (WTO). What was particular about the Geneva School of neoliberalism?

Quinn Slobodian: What occurred to me was that capitalism hadn’t really had to deal with democracy until the twentieth century. It could reproduce itself and all of its inequalities by simply keeping some people out of the political picture, and denying them a voice in the political process.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, most of the world was in colonial status. The parts of the world that were in the metropole—the center of the empire, or had independence like the United States or Latin American countries—did not have anything close to universal suffrage. Women in every case were still denied the right to vote—allowing women to vote happened experimentally within the Paris Commune in the 1870s, but was quickly withdrawn and was only rolled out in exceptional cases more after the First World War. And in places like France, not until the Second World War.

So, the core question for Vienna school neoliberals in the 1920s and 1930s was first of all how to expand the voice within rich Western populations to include people without property and women. And then how to expand it beyond Europe to the former colonial countries of Asia, Africa, and parts of Latin America. And how to do that while preserving a system which has been proven to produce jaw-dropping inequalities between populations and parts of the world.

The first problem that they saw was decolonization. The dissolution of the Habsburg Empire after the First World War accompanied the end of the Russian and Ottoman Empires. It was the triumph of the nationality principle for the first time. That also came along with a certain idea of self-determination and popular sovereignty at the national level, which was more asserted than practiced until after the First World War.

More here.

Last week, the Wall Street Journal published a troubling exposé on the crushing debt burdens that students accumulate while pursuing master’s degrees at elite universities in fields like drama and film, where the job prospects are limited and the chances of making enough to repay their debt are slim. Because it focused on MFA programs at Ivy League schools—one subject accumulated around $300,000 in loans pursuing screenwriting—the article rocketed around the creative class on Twitter. But it also pointed to a more fundamental, troubling development in the world of higher education: For colleges and universities, master’s degrees have essentially become an enormous moneymaking scheme, wherein the line between for-profit and nonprofit education has been utterly blurred. There are, of course, good programs as well as bad ones, but when you scope out, there is clearly a systemic problem.

Last week, the Wall Street Journal published a troubling exposé on the crushing debt burdens that students accumulate while pursuing master’s degrees at elite universities in fields like drama and film, where the job prospects are limited and the chances of making enough to repay their debt are slim. Because it focused on MFA programs at Ivy League schools—one subject accumulated around $300,000 in loans pursuing screenwriting—the article rocketed around the creative class on Twitter. But it also pointed to a more fundamental, troubling development in the world of higher education: For colleges and universities, master’s degrees have essentially become an enormous moneymaking scheme, wherein the line between for-profit and nonprofit education has been utterly blurred. There are, of course, good programs as well as bad ones, but when you scope out, there is clearly a systemic problem.

Nancy Kathryn Walecki: So first of all, most people probably think of psychedelics in the context of the 1960s countercultural movements, when they were being used recreationally. So is using psychedelic drugs in psychiatric treatment a new idea?

Nancy Kathryn Walecki: So first of all, most people probably think of psychedelics in the context of the 1960s countercultural movements, when they were being used recreationally. So is using psychedelic drugs in psychiatric treatment a new idea? E

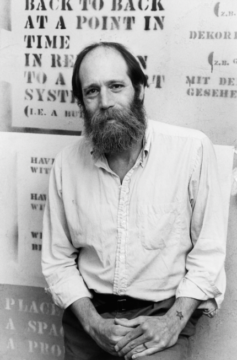

E Lawrence Weiner, a towering figure in the Conceptual art movement arising in the 1960s and who profoundly altered the landscape of American art, died December 2 at the age of seventy-nine. Known for his text-based installations incorporating evocative or descriptive phrases and sentence fragments, typically presented in bold capital letters accompanied by graphic accents and occupying unusual sites and surfaces, Weiner rose to prominence among a cohort that included Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, and Sol LeWitt. A firm believer that an idea alone could constitute an artwork, he established a practice that stood out for its consistent embodiment of his famous 1968 “Declaration of Intent”:

Lawrence Weiner, a towering figure in the Conceptual art movement arising in the 1960s and who profoundly altered the landscape of American art, died December 2 at the age of seventy-nine. Known for his text-based installations incorporating evocative or descriptive phrases and sentence fragments, typically presented in bold capital letters accompanied by graphic accents and occupying unusual sites and surfaces, Weiner rose to prominence among a cohort that included Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, and Sol LeWitt. A firm believer that an idea alone could constitute an artwork, he established a practice that stood out for its consistent embodiment of his famous 1968 “Declaration of Intent”: “Stephen’s story is well documented, the pain of it. Now here he was writing a beautiful song for the mother and wanting to write the son’s part. I had a relationship with my mother that I don’t think was as difficult, it had a little more grace, but it was challenging nonetheless. Stephen and I came to the conclusion that we never made the connection in the way we were searching for it. We kept passing by each other like ships in the night. A few days later, he hands me my part of the mother’s song. He’d taken our conversation and poeticised it. I got to be a teeny tiny part of what he was trying to say for this character. He wrote the most beautiful love song of two human beings trying to reach each other. That was the highlight of my entire professional life.”

“Stephen’s story is well documented, the pain of it. Now here he was writing a beautiful song for the mother and wanting to write the son’s part. I had a relationship with my mother that I don’t think was as difficult, it had a little more grace, but it was challenging nonetheless. Stephen and I came to the conclusion that we never made the connection in the way we were searching for it. We kept passing by each other like ships in the night. A few days later, he hands me my part of the mother’s song. He’d taken our conversation and poeticised it. I got to be a teeny tiny part of what he was trying to say for this character. He wrote the most beautiful love song of two human beings trying to reach each other. That was the highlight of my entire professional life.” Brian Callaci in The Boston Review:

Brian Callaci in The Boston Review: Yulia Gromova interviews Quinn Slobodian in Strelka:

Yulia Gromova interviews Quinn Slobodian in Strelka: The self-help industry is booming, fuelled by research on

The self-help industry is booming, fuelled by research on  On a May evening in 1959, C.P. Snow, a popular novelist and former research scientist, gave a lecture before a gathering of dons and students at the University of Cambridge, his alma mater. He called his talk “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.” Snow declared that a gulf of mutual incomprehension divided literary intellectuals and scientists.

On a May evening in 1959, C.P. Snow, a popular novelist and former research scientist, gave a lecture before a gathering of dons and students at the University of Cambridge, his alma mater. He called his talk “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.” Snow declared that a gulf of mutual incomprehension divided literary intellectuals and scientists. Several years ago, I met Francis Bacon’s cleaning lady. Bacon’s amanuensis, the art critic David Sylvester, referred me to her, as he had her to Bacon. Jean Ward, who had her grey hair swept back into a thin ponytail like a pirate’s, welcomed me to her flat on a housing estate in Tooting Beck, South London. In a raspy voice she told me about her decade working for the painter whose legendarily messy studio—layer upon layer of dust, paint, discarded imagery, champagne bottles, and other detritus—would not have provided her much of a recommendation for future jobs.

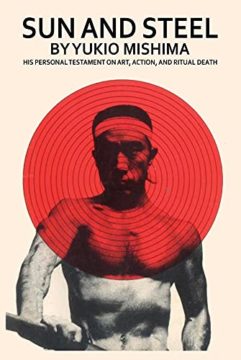

Several years ago, I met Francis Bacon’s cleaning lady. Bacon’s amanuensis, the art critic David Sylvester, referred me to her, as he had her to Bacon. Jean Ward, who had her grey hair swept back into a thin ponytail like a pirate’s, welcomed me to her flat on a housing estate in Tooting Beck, South London. In a raspy voice she told me about her decade working for the painter whose legendarily messy studio—layer upon layer of dust, paint, discarded imagery, champagne bottles, and other detritus—would not have provided her much of a recommendation for future jobs. He poses on the cover of my old Grove Press edition in the aspect of a warrior, stripped to the waist, forehead bound in a hachimaki, looking out from under heavy brows. His shadowed gaze is intent, unnerving. His left cheekbone and the strong bridge of his nose catch the light. (A humanizing touch: his ears stick out slightly too far.) In a suit he might seem ordinary, at best of average build, but shirtless he is a panther ready to spring. His forearms are unusually furry for a Japanese man, his concave stomach bifurcated by a line of black hair. His triceps resemble warm marble. Superimposed on this fierce portrait are the concentric rings of a red target, as though Mishima were about to be feathered with arrows like St. Sebastian—a picture of whose “white and matchless nudity” moves the frail narrator of Mishima’s novel Confessions of a Mask to his first ejaculation. In the center of this target, his grim mouth forms the bull’s-eye; the outer rings drape his shoulders and pectoral muscles like a mantle of blood. His right hand is drawing out of its sheath, upward into the frame, the naked blade of a samurai sword.

He poses on the cover of my old Grove Press edition in the aspect of a warrior, stripped to the waist, forehead bound in a hachimaki, looking out from under heavy brows. His shadowed gaze is intent, unnerving. His left cheekbone and the strong bridge of his nose catch the light. (A humanizing touch: his ears stick out slightly too far.) In a suit he might seem ordinary, at best of average build, but shirtless he is a panther ready to spring. His forearms are unusually furry for a Japanese man, his concave stomach bifurcated by a line of black hair. His triceps resemble warm marble. Superimposed on this fierce portrait are the concentric rings of a red target, as though Mishima were about to be feathered with arrows like St. Sebastian—a picture of whose “white and matchless nudity” moves the frail narrator of Mishima’s novel Confessions of a Mask to his first ejaculation. In the center of this target, his grim mouth forms the bull’s-eye; the outer rings drape his shoulders and pectoral muscles like a mantle of blood. His right hand is drawing out of its sheath, upward into the frame, the naked blade of a samurai sword. A blurb on the cover of my copy of Lolita calls the novel “the only convincing love story of our century.”

A blurb on the cover of my copy of Lolita calls the novel “the only convincing love story of our century.”