Ian McEwan in New Statesman:

Ian McEwan in New Statesman:

I’ll start with a place, a Paris apartment in Montparnasse, and a date, 23 December 1936, and a gift from one writer to another of his corduroy jacket which, from the point of view of the recipient, may have had a few traces of whale blubber attached to its lapels. The generous donor was the American writer Henry Miller. He thought his visitor, George Orwell, on his way to Spain to fight in the civil war, would benefit from its warmth through the Spanish winter, though he pointed out that it was not bulletproof. The present, Miller said, was his contribution to the loyalist anti-fascist cause.

The encounter between the two men (the American was almost 45, the Englishman 33) had been well smoothed in advance by Orwell’s positive review of Miller’s novel, Tropic of Cancer, which was followed by a collegiate exchange of letters. The meeting presents us with a tableau vivant and source for the heart of Orwell’s celebrated essay “Inside the Whale”, published in book form just over three years later in 1940 by Gollancz. Despite a fair degree of mutual admiration, these two writers had much to disagree about. Henry Miller, self-exiled, strenuously bohemian, a cultural pessimist, hedonist, tirelessly sexually active – or tiresomely, as second wave feminists would point out through the Seventies. He had a profound disregard for politics and political activism of any kind. As a writer, he was, by Orwell’s definition, “inside the whale”. Such political views as Miller had were naive and self-regarding and light-hearted. In a letter to Lawrence Durrell he wrote that he knew he could head off the rise of Nazism and the threat of war if he could just get five minutes alone with Adolf Hitler and make him laugh.

More here.

2021 is the 6th year we’re approaching experts and asking them to recommend the best books published in their field, whether it’s history or historical fiction, science or science fiction, math or memoir, politics or philosophy.

2021 is the 6th year we’re approaching experts and asking them to recommend the best books published in their field, whether it’s history or historical fiction, science or science fiction, math or memoir, politics or philosophy.

The family has been an infinite well of inspiration for photographers for as long as the medium has existed. From Larry Sultan’s Pictures From Home to LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family, the family unit has proved a conduit for explorations of belonging, identity, strife, place, connection, injustice and more. Photographers have both worked behind the camera and stepped into the frame in order to capture the most universal of subjects, the complications and connections to those we love.

The family has been an infinite well of inspiration for photographers for as long as the medium has existed. From Larry Sultan’s Pictures From Home to LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family, the family unit has proved a conduit for explorations of belonging, identity, strife, place, connection, injustice and more. Photographers have both worked behind the camera and stepped into the frame in order to capture the most universal of subjects, the complications and connections to those we love. Claudia Goldin, Henry Lee professor of economics, shares the reason why working mothers still earn less and advance less often in their careers than men: time. Even with antidiscrimination laws and unbiased managers, certain professions pay employees disproportionately more for long hours and weekends, passing over women who need that time for family care. Goldin also discusses how COVID-19’s flexible work policies may help close the gender earnings gap.

Claudia Goldin, Henry Lee professor of economics, shares the reason why working mothers still earn less and advance less often in their careers than men: time. Even with antidiscrimination laws and unbiased managers, certain professions pay employees disproportionately more for long hours and weekends, passing over women who need that time for family care. Goldin also discusses how COVID-19’s flexible work policies may help close the gender earnings gap. Cora Currier in The Nation:

Cora Currier in The Nation: In the L.A. Review of Books:

In the L.A. Review of Books: Henry Farrell and Glen Weyl in Boston Review:

Henry Farrell and Glen Weyl in Boston Review: Ian McEwan in New Statesman:

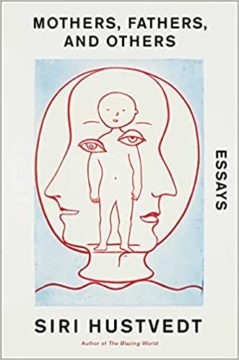

Ian McEwan in New Statesman: When Hustvedt returns to the idea of what’s missing, her writing takes off. In “Both-And,” an essay on Bourgeois, she offers the concept of intercorporeality from French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty: “that human relations take place between and among bodies, that we perceive and understand others in embodied ways that are not conscious.” What could be more loaded than the mother’s body, a body that is not one, but two? A body that is no longer hers alone? “The artist sees the object unfold, a thing that rises out of you, is related to you, but is not you either,” Hustvedt writes about Bourgeois’ work. But this easily applies to birth and mothering.

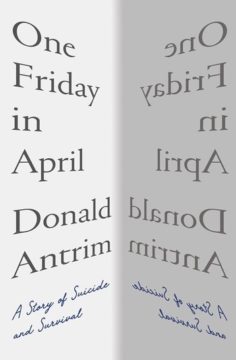

When Hustvedt returns to the idea of what’s missing, her writing takes off. In “Both-And,” an essay on Bourgeois, she offers the concept of intercorporeality from French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty: “that human relations take place between and among bodies, that we perceive and understand others in embodied ways that are not conscious.” What could be more loaded than the mother’s body, a body that is not one, but two? A body that is no longer hers alone? “The artist sees the object unfold, a thing that rises out of you, is related to you, but is not you either,” Hustvedt writes about Bourgeois’ work. But this easily applies to birth and mothering. One Friday begins on a Friday in April 2006, when the forty-seven-year-old Antrim, having just had a spat with his girlfriend, is clinging to the fire escape of his four-story apartment building in Brooklyn, considering jumping to his death. (Although one wonders if falling from this height might have resulted in serious injury rather than death.) “I didn’t know why I had to fall from the roof,” he writes, “why that was mine to do.” He goes on to tell us that depression is a “misleading term,” that he prefers to call his depression “suicide” because he sees it “as a long illness, an illness with origins in trauma and isolation” rather than “the death, the fall from a height or the trigger pulled.” Although Antrim offers this explanation as an original take on an enigmatic condition, I found it befuddling rather than clarifying: suicide is sudden and immediate while depression is a long and often recurrent illness. There is no getting around it: the former is a decision, however impulsive and catastrophic; the latter is a passively endured condition, the result of our chemistry and psychological vulnerabilities.

One Friday begins on a Friday in April 2006, when the forty-seven-year-old Antrim, having just had a spat with his girlfriend, is clinging to the fire escape of his four-story apartment building in Brooklyn, considering jumping to his death. (Although one wonders if falling from this height might have resulted in serious injury rather than death.) “I didn’t know why I had to fall from the roof,” he writes, “why that was mine to do.” He goes on to tell us that depression is a “misleading term,” that he prefers to call his depression “suicide” because he sees it “as a long illness, an illness with origins in trauma and isolation” rather than “the death, the fall from a height or the trigger pulled.” Although Antrim offers this explanation as an original take on an enigmatic condition, I found it befuddling rather than clarifying: suicide is sudden and immediate while depression is a long and often recurrent illness. There is no getting around it: the former is a decision, however impulsive and catastrophic; the latter is a passively endured condition, the result of our chemistry and psychological vulnerabilities. Donald Trump, however, will not say this. He has spent the year since he lost insisting that he won. His supporters believe the same.

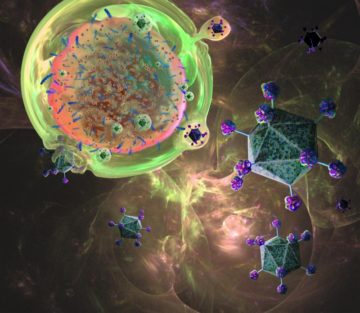

Donald Trump, however, will not say this. He has spent the year since he lost insisting that he won. His supporters believe the same.  It seemed like a very promising cancer immunotherapy lead. CHO Pharma, in Taiwan, had discovered that it was possible to target solid tumours with an antibody against a cell-surface glycolipid called SSEA-4.

It seemed like a very promising cancer immunotherapy lead. CHO Pharma, in Taiwan, had discovered that it was possible to target solid tumours with an antibody against a cell-surface glycolipid called SSEA-4.

The detonation of the

The detonation of the  Jean Luc remembers how, when he was very young, his parents would leave their house in Kimihurura, a neighborhood of Kigali, once a month in a good mood. He didn’t know what they were smiling about.

Jean Luc remembers how, when he was very young, his parents would leave their house in Kimihurura, a neighborhood of Kigali, once a month in a good mood. He didn’t know what they were smiling about.