Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World:

Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World:

If central banks were ambitious about shrinking private lending to carbon activities, the COP26 press release would have announced plans to explicitly penalize dirty lending in both monetary policy and regulatory frameworks, and specified an ambitious timeline for doing so. These plans would upgrade the Bank of England’s “carrots first, sticks later” approach to decarbonizing its corporate bond purchases (which first rewards, and only later envisages penalizing) to a carrots and sticks approach better aligned with the climate urgency. By rapidly ending the historical carbon bias hardwired into collateral frameworks and unconventional corporate bond purchases, as they have repeatedly promised to do, central banks would ensure that the cost of capital for high carbon activities increases significantly, redirecting financial flows to green activities.

To minimize dirty arbitrage (fossil assets shifting across private portfolios), the central banks might announce the inclusion of private equity and other shadow banks within the scope of the new “carrots and sticks” regime. To further reduce transition risks and preserve an orderly transition, they could recommend new accounting rules for stranded assets (suspending mark to market) in systemic institutional portfolios.

Central banks would also address the structural shortage of green assets by calling on fiscal authorities to collectively develop new regimes of green macro-coordination. The accelerated issuance of green sovereign bonds could absorb the flow of capital leaving dirty activities, and finance nationally-developed green public investment plans and green industrial policies. This might come alongside increased taxation of conspicuous luxury consumption and avoid carbon shock therapy by carefully deploying carbon prices without allowing them to dictate the pace and direction of decarbonization.

More here.

Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar:

Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar: Adam Tooze over at site Chartbook:

Adam Tooze over at site Chartbook: “Attack” didn’t seem like the right word, and neither did “mauling.” In Nastassja Martin’s new book, “In the Eye of the Wild,” she calls it “combat” before eventually settling on “the encounter between the bear and me.” She suggests that what happened on Aug. 25, 2015, in the mountains of Kamchatka, in eastern Siberia, wasn’t simply a matter of a fierce animal overpowering a terrified human — though Martin almost died before she pulled out the ice ax she was carrying and drove it into the bear’s leg. Waiting for help, she saw that everything was red: her face, her hands, the ground.

“Attack” didn’t seem like the right word, and neither did “mauling.” In Nastassja Martin’s new book, “In the Eye of the Wild,” she calls it “combat” before eventually settling on “the encounter between the bear and me.” She suggests that what happened on Aug. 25, 2015, in the mountains of Kamchatka, in eastern Siberia, wasn’t simply a matter of a fierce animal overpowering a terrified human — though Martin almost died before she pulled out the ice ax she was carrying and drove it into the bear’s leg. Waiting for help, she saw that everything was red: her face, her hands, the ground. W

W Stephen Sondheim, one of Broadway history’s songwriting titans, whose music and lyrics raised and reset the artistic standard for the American stage musical, died early Friday at his home in Roxbury, Conn. He was 91. His lawyer and friend, F. Richard Pappas, announced the death. He said he did not know the cause but added that Mr. Sondheim had not been known to be ill and that the death was sudden. The day before, Mr. Sondheim had celebrated Thanksgiving with a dinner with friends in Roxbury, Mr. Pappas said.

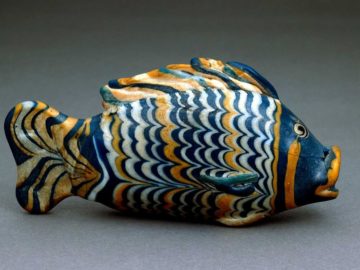

Stephen Sondheim, one of Broadway history’s songwriting titans, whose music and lyrics raised and reset the artistic standard for the American stage musical, died early Friday at his home in Roxbury, Conn. He was 91. His lawyer and friend, F. Richard Pappas, announced the death. He said he did not know the cause but added that Mr. Sondheim had not been known to be ill and that the death was sudden. The day before, Mr. Sondheim had celebrated Thanksgiving with a dinner with friends in Roxbury, Mr. Pappas said. Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a

Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a

Fraud in biomedical research, though relatively uncommon, damages the scientific community by diminishing the integrity of the ecosystem and sending other scientists down fruitless paths. When exposed and publicized, fraud also reduces public respect for the research enterprise, which is required for its success. Although the human frailties that contribute to fraud are as old as our species, the response of the research community to allegations of fraud has dramatically changed. This is well illustrated by three prominent cases known to the author over 40 years. In the first, I participated as auditor in an ad hoc process that, lacking institutional definition and oversight, was open to abuse, though it eventually produced an appropriate result. In the second, I was a faculty colleague of a key participant whose case helped shape guidelines for management of future cases. The third transpired during my time overseeing the well-developed if sometimes overly bureaucratized investigatory process for research misconduct at Harvard Medical School, designed in accordance with prevailing regulations. These cases illustrate many of the factors contributing to fraudulent biomedical research in the modern era and the changing institutional responses to it, which should further evolve to be more efficient and transparent.

Fraud in biomedical research, though relatively uncommon, damages the scientific community by diminishing the integrity of the ecosystem and sending other scientists down fruitless paths. When exposed and publicized, fraud also reduces public respect for the research enterprise, which is required for its success. Although the human frailties that contribute to fraud are as old as our species, the response of the research community to allegations of fraud has dramatically changed. This is well illustrated by three prominent cases known to the author over 40 years. In the first, I participated as auditor in an ad hoc process that, lacking institutional definition and oversight, was open to abuse, though it eventually produced an appropriate result. In the second, I was a faculty colleague of a key participant whose case helped shape guidelines for management of future cases. The third transpired during my time overseeing the well-developed if sometimes overly bureaucratized investigatory process for research misconduct at Harvard Medical School, designed in accordance with prevailing regulations. These cases illustrate many of the factors contributing to fraudulent biomedical research in the modern era and the changing institutional responses to it, which should further evolve to be more efficient and transparent. In March 2020, Boris Johnson, pale and exhausted, self-isolating in his flat on Downing Street, released a video of himself – that he had taken himself – reassuring Britons that they would get through the pandemic, together. “One thing I think the coronavirus crisis has already proved is that there really is such a thing as society,” the prime minister

In March 2020, Boris Johnson, pale and exhausted, self-isolating in his flat on Downing Street, released a video of himself – that he had taken himself – reassuring Britons that they would get through the pandemic, together. “One thing I think the coronavirus crisis has already proved is that there really is such a thing as society,” the prime minister  I thought often about something the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders said, after

I thought often about something the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders said, after  Why have I come so far on a literary pilgrimage? I want to be unafraid to move in the world again. But what do I expect from a visit to the three-quarters-Canadian, one-quarter-American poet Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood home? “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” Bishop asks in her marvelous poem “Questions of Travel.” Am I, like her, dreaming my dream and having it too? Is it a lack of imagination that brings me to Great Village? “Shouldn’t you have stayed at home and thought of here?” I can hear her asking. I wish my friend Rachel were here as planned. She would know the answers to these questions. She is receiving a new treatment and isn’t herself. In 1979, on the weekend that Bishop died, Rachel knocked on her door at 437 Lewis Wharf—Rachel still lives upstairs—because she knew Bishop wasn’t feeling well, and offered to bring her some milk and eggs from the local market, but Bishop demurred. A couple of days later, Bishop’s friend and companion Alice Methfessel phoned to say that Elizabeth had died and that she didn’t want Rachel to be shocked to read about it in the newspaper.

Why have I come so far on a literary pilgrimage? I want to be unafraid to move in the world again. But what do I expect from a visit to the three-quarters-Canadian, one-quarter-American poet Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood home? “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” Bishop asks in her marvelous poem “Questions of Travel.” Am I, like her, dreaming my dream and having it too? Is it a lack of imagination that brings me to Great Village? “Shouldn’t you have stayed at home and thought of here?” I can hear her asking. I wish my friend Rachel were here as planned. She would know the answers to these questions. She is receiving a new treatment and isn’t herself. In 1979, on the weekend that Bishop died, Rachel knocked on her door at 437 Lewis Wharf—Rachel still lives upstairs—because she knew Bishop wasn’t feeling well, and offered to bring her some milk and eggs from the local market, but Bishop demurred. A couple of days later, Bishop’s friend and companion Alice Methfessel phoned to say that Elizabeth had died and that she didn’t want Rachel to be shocked to read about it in the newspaper. Richard Rorty (1931–2007) was the philosopher’s anti-philosopher. His professional credentials were impeccable: an influential anthology (The Linguistic Turn, 1967); a game-changing book (Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, 1979); another, only slightly less original book (Consequences of Pragmatism, 1982); a best-selling (for a philosopher) collection of literary/philosophical/political lectures and essays (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 1989); four volumes of Collected Papers from the venerable Cambridge University Press; president of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association (1979). He seemed to be speaking at every humanities conference in the 1980s and 1990s, about postmodernism, critical theory, deconstruction, and the past, present, and future (if any) of philosophy.

Richard Rorty (1931–2007) was the philosopher’s anti-philosopher. His professional credentials were impeccable: an influential anthology (The Linguistic Turn, 1967); a game-changing book (Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, 1979); another, only slightly less original book (Consequences of Pragmatism, 1982); a best-selling (for a philosopher) collection of literary/philosophical/political lectures and essays (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 1989); four volumes of Collected Papers from the venerable Cambridge University Press; president of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association (1979). He seemed to be speaking at every humanities conference in the 1980s and 1990s, about postmodernism, critical theory, deconstruction, and the past, present, and future (if any) of philosophy. Tiny is pregnant, but not as we know it: she is expecting an “owl-baby”, the result of a secret tryst with a female “owl-lover”. “This baby will never learn to speak, or love, or look after itself”, Tiny knows. Her husband, an intellectual property lawyer, thinks her panic is just pregnancy jitters, and that she’s carrying his child. Even when he finds a disembowelled possum on the path and his “well fed” wife sitting in the dark (“It didn’t feel dark to me. I see everything”), he doesn’t believe. Then the baby is born.

Tiny is pregnant, but not as we know it: she is expecting an “owl-baby”, the result of a secret tryst with a female “owl-lover”. “This baby will never learn to speak, or love, or look after itself”, Tiny knows. Her husband, an intellectual property lawyer, thinks her panic is just pregnancy jitters, and that she’s carrying his child. Even when he finds a disembowelled possum on the path and his “well fed” wife sitting in the dark (“It didn’t feel dark to me. I see everything”), he doesn’t believe. Then the baby is born. In her preface to the 2021 paperback edition of Thanksgiving, marking the 400th anniversary of the American Thanksgiving, Melanie Kirkpatrick expresses her concern for the continued celebration of the venerable holiday. “Given recent attacks on Washington, Lincoln, and other heroes of American history, it was only a matter of time before cancel culture came for Thanksgiving.” (x) Her use of the word “heroes” clearly places her on a particular side in this installment of the culture wars, but her worry is legitimate. Thanksgiving could fall, condemned as a symbol, a relic of White supremacy, simultaneously celebrating and masking genocide, colonialism, and racism, just as Columbus Day has died an ignoble (and for many a deserved) death across a good swath of the United States. The fact that Kirkpatrick does not touch upon this at all in the introduction to the 2016 edition of her book shows just how decisive (Kirkpatrick would probably say destructive) a force cancel culture has become in a mere five years.

In her preface to the 2021 paperback edition of Thanksgiving, marking the 400th anniversary of the American Thanksgiving, Melanie Kirkpatrick expresses her concern for the continued celebration of the venerable holiday. “Given recent attacks on Washington, Lincoln, and other heroes of American history, it was only a matter of time before cancel culture came for Thanksgiving.” (x) Her use of the word “heroes” clearly places her on a particular side in this installment of the culture wars, but her worry is legitimate. Thanksgiving could fall, condemned as a symbol, a relic of White supremacy, simultaneously celebrating and masking genocide, colonialism, and racism, just as Columbus Day has died an ignoble (and for many a deserved) death across a good swath of the United States. The fact that Kirkpatrick does not touch upon this at all in the introduction to the 2016 edition of her book shows just how decisive (Kirkpatrick would probably say destructive) a force cancel culture has become in a mere five years.