Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack newsletter, Hinternet:

Just minutes after St. Nicholas was born, on December 6, he stood up on his own two feet in the basin where the midwives washed him, and completed the task himself. Then the babe grabbed a knife from the table and severed his own umbilical cord. Through the rest of his infancy he refused to nurse more than twice a week, and only ever on Wednesdays and Fridays. As Nicholas grew older he developed a sharp hatred of sin, and wept whenever he witnessed it. Having inherited a great wealth from his parents, he decided to fight sin through what you might today call “effective altruism”. When he overheard his neighbor announcing a plan to sell his two daughters into prostitution in order to lighten his debts, Nicholas contrived to throw a sack of gold coins through the neighbor’s window in the middle of the night (the sled and reindeer, we may imagine, are later accretions upon the legend). After a life of such good works, when he died in 313 AD, oil poured from his head, and water from his feet, and continued to pour for some centuries after that from the site of his burial, when such things as this still occurred.

Just minutes after St. Nicholas was born, on December 6, he stood up on his own two feet in the basin where the midwives washed him, and completed the task himself. Then the babe grabbed a knife from the table and severed his own umbilical cord. Through the rest of his infancy he refused to nurse more than twice a week, and only ever on Wednesdays and Fridays. As Nicholas grew older he developed a sharp hatred of sin, and wept whenever he witnessed it. Having inherited a great wealth from his parents, he decided to fight sin through what you might today call “effective altruism”. When he overheard his neighbor announcing a plan to sell his two daughters into prostitution in order to lighten his debts, Nicholas contrived to throw a sack of gold coins through the neighbor’s window in the middle of the night (the sled and reindeer, we may imagine, are later accretions upon the legend). After a life of such good works, when he died in 313 AD, oil poured from his head, and water from his feet, and continued to pour for some centuries after that from the site of his burial, when such things as this still occurred.

More here.

Consciousness is such a slippery and ephemeral concept that it doesn’t even have its own word in many Romance languages, but nevertheless it’s a hot topic these days. “Feeling & Knowing” is the result of Damasio’s editor’s request to weigh in on the subject by writing a very short, very focused book. Over 200 pages, Damasio ponders profound questions: How did we get here? How did we develop minds with mental maps, a constant stream of images, and memories — mechanisms that exist symbiotically with the feelings and sensations in our bodies that we then, crucially, relate back to ourselves and associate with a sense of personhood?

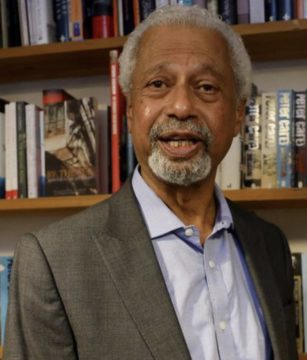

Consciousness is such a slippery and ephemeral concept that it doesn’t even have its own word in many Romance languages, but nevertheless it’s a hot topic these days. “Feeling & Knowing” is the result of Damasio’s editor’s request to weigh in on the subject by writing a very short, very focused book. Over 200 pages, Damasio ponders profound questions: How did we get here? How did we develop minds with mental maps, a constant stream of images, and memories — mechanisms that exist symbiotically with the feelings and sensations in our bodies that we then, crucially, relate back to ourselves and associate with a sense of personhood? Many readers around the world are still just discovering Abdulrazak Gurnah. After his winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2021 – which almost no one saw coming – the 72-year-old Zanzibar-born author is finally in the limelight that was perhaps due to him for a few decades now.

Many readers around the world are still just discovering Abdulrazak Gurnah. After his winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2021 – which almost no one saw coming – the 72-year-old Zanzibar-born author is finally in the limelight that was perhaps due to him for a few decades now. W

W Our science delivers a lot of exciting breakthroughs to make life better today. But we’re also busy working behind-the-scenes on science that takes a bit longer to develop. Science that will significantly change what the future looks like. We call these areas of cutting-edge research our

Our science delivers a lot of exciting breakthroughs to make life better today. But we’re also busy working behind-the-scenes on science that takes a bit longer to develop. Science that will significantly change what the future looks like. We call these areas of cutting-edge research our  One year earlier, in the first throes of my renewed interest in the Manson Family, I had taken the Helter Skelter bus tour operated by Dearly Departed, an outfit specializing in Los Angeles death and murder sites. It sells out nearly every weekend, which is surprising given that there’s actually not much to see anymore. Scott Michaels, Dearly Departed’s founder and main guide, set the tone with a custom soundtrack of hits from 1969 (“In the Year 2525,” “Hair”), cozy oldies made newly spooky by our proximity to death. He also included extensive multimedia add-ons, such as cleavage-heavy clips from Sharon Tate’s early films and Jay Sebring’s cameo on the old bang-pow Batman TV show. Going on the tour is a little like taking a road trip through the parking lots and strip malls of central Los Angeles, accompanied by a group of strangers wearing various skull accessories. Many of the sites aren’t visible or no longer exist. The former Tate-Polanski house on Cielo Drive has been demolished; the site of Rosemary and Leno LaBianca’s murders in Los Feliz is mostly hidden by a hedge.

One year earlier, in the first throes of my renewed interest in the Manson Family, I had taken the Helter Skelter bus tour operated by Dearly Departed, an outfit specializing in Los Angeles death and murder sites. It sells out nearly every weekend, which is surprising given that there’s actually not much to see anymore. Scott Michaels, Dearly Departed’s founder and main guide, set the tone with a custom soundtrack of hits from 1969 (“In the Year 2525,” “Hair”), cozy oldies made newly spooky by our proximity to death. He also included extensive multimedia add-ons, such as cleavage-heavy clips from Sharon Tate’s early films and Jay Sebring’s cameo on the old bang-pow Batman TV show. Going on the tour is a little like taking a road trip through the parking lots and strip malls of central Los Angeles, accompanied by a group of strangers wearing various skull accessories. Many of the sites aren’t visible or no longer exist. The former Tate-Polanski house on Cielo Drive has been demolished; the site of Rosemary and Leno LaBianca’s murders in Los Feliz is mostly hidden by a hedge. Davidson is evidently a great wanderer and his book, largely an account of his nocturnal wanderings and the thoughts inspired by them, is itself an engagingly wandering affair. It is a work of great charm, moving from text to text and painting to painting in a disarmingly associative way: the connective tissue of the work is a network of phrases such as ‘My mind circles back…’, ‘I think of other lights which shine in more than one dimension…’, ‘I am reminded of an odd fragment of narrative…’ and ‘My thoughts moved to a far comparison…’. We begin and end accompanying the author through the crepuscular autumnal fog beside the Thames in Oxford, and in between we follow him through the sighing willows of Ghent, the frozen mid-afternoon darkness of Stockholm, the scruffy urban romance of central London, the smart neoclassical streets of Edinburgh’s New Town, the autumnal fields of Norfolk and the snows of Princeton. And as we make our way, Davidson tells us what emerges from his extraordinarily well-stocked mind.

Davidson is evidently a great wanderer and his book, largely an account of his nocturnal wanderings and the thoughts inspired by them, is itself an engagingly wandering affair. It is a work of great charm, moving from text to text and painting to painting in a disarmingly associative way: the connective tissue of the work is a network of phrases such as ‘My mind circles back…’, ‘I think of other lights which shine in more than one dimension…’, ‘I am reminded of an odd fragment of narrative…’ and ‘My thoughts moved to a far comparison…’. We begin and end accompanying the author through the crepuscular autumnal fog beside the Thames in Oxford, and in between we follow him through the sighing willows of Ghent, the frozen mid-afternoon darkness of Stockholm, the scruffy urban romance of central London, the smart neoclassical streets of Edinburgh’s New Town, the autumnal fields of Norfolk and the snows of Princeton. And as we make our way, Davidson tells us what emerges from his extraordinarily well-stocked mind. Boeing’s self-hijacking plane took its first 189 lives on October 29, 2018, just over two months after it had been

Boeing’s self-hijacking plane took its first 189 lives on October 29, 2018, just over two months after it had been  We all know you can’t derive “ought” from “is.” But it’s equally clear that “is” — how the world actual works — is going to matter for “ought” — our moral choices in the world. And an important part of “is” is who we are as human beings. As products of a messy evolutionary history, we all have moral intuitions. What parts of the brain light up when we’re being consequentialist, or when we’re following rules? What is the relationship, if any, between those intuitions and a good moral philosophy? Joshua Greene is both a philosopher and a psychologist who studies what our intuitions are, and uses that to help illuminate what morality should be. He gives one of the best defenses of utilitarianism I’ve heard.

We all know you can’t derive “ought” from “is.” But it’s equally clear that “is” — how the world actual works — is going to matter for “ought” — our moral choices in the world. And an important part of “is” is who we are as human beings. As products of a messy evolutionary history, we all have moral intuitions. What parts of the brain light up when we’re being consequentialist, or when we’re following rules? What is the relationship, if any, between those intuitions and a good moral philosophy? Joshua Greene is both a philosopher and a psychologist who studies what our intuitions are, and uses that to help illuminate what morality should be. He gives one of the best defenses of utilitarianism I’ve heard. At last month’s COP26 climate summit, hundreds of financial institutions declared that they would put trillions of dollars to work to finance solutions to climate change. Yet a major barrier stands in the way: The world’s financial system actually impedes the flow of finance to developing countries, creating a financial death trap for many.

At last month’s COP26 climate summit, hundreds of financial institutions declared that they would put trillions of dollars to work to finance solutions to climate change. Yet a major barrier stands in the way: The world’s financial system actually impedes the flow of finance to developing countries, creating a financial death trap for many. W

W The New Mexican desert unrolled on either side of the highway like a canvas spangled at intervals by the smallest of towns. I was on a road trip with my 20-year-old son from our home in Los Angeles to his college in Michigan. Eli, trying to be patient, plowed down I-40 as daylight dimmed and I scrolled through my phone searching for a restaurant or dish that would not cause me pain. After years of carefully navigating dinners out and meals in, it had finally happened: There was nowhere I could eat.

The New Mexican desert unrolled on either side of the highway like a canvas spangled at intervals by the smallest of towns. I was on a road trip with my 20-year-old son from our home in Los Angeles to his college in Michigan. Eli, trying to be patient, plowed down I-40 as daylight dimmed and I scrolled through my phone searching for a restaurant or dish that would not cause me pain. After years of carefully navigating dinners out and meals in, it had finally happened: There was nowhere I could eat. I

I To look back in time at the cosmos’s infancy and witness the first stars flicker on, you must first grind a mirror as big as a house. Its surface must be so smooth that, if the mirror were the scale of a continent, it would feature no hill or valley greater than ankle height. Only a mirror so huge and smooth can collect and focus the faint light coming from the farthest galaxies in the sky — light that left its source long ago and therefore shows the galaxies as they appeared in the ancient past, when the universe was young. The very faintest, farthest galaxies we would see still in the process of being born, when mysterious forces conspired in the dark and the first crops of stars started to shine.

To look back in time at the cosmos’s infancy and witness the first stars flicker on, you must first grind a mirror as big as a house. Its surface must be so smooth that, if the mirror were the scale of a continent, it would feature no hill or valley greater than ankle height. Only a mirror so huge and smooth can collect and focus the faint light coming from the farthest galaxies in the sky — light that left its source long ago and therefore shows the galaxies as they appeared in the ancient past, when the universe was young. The very faintest, farthest galaxies we would see still in the process of being born, when mysterious forces conspired in the dark and the first crops of stars started to shine. With its doctrine of fairness, A Theory of Justice transformed political philosophy. The English historian Peter Laslett had described the field as “dead” in 1956; with Rawls’s book that changed almost overnight. Now philosophers were arguing about the nature of Rawlsian principles and their implications—and for that matter were once again interested in matters of political and economic justice. Rawls’s terms became lingua franca: Many considered how his arguments, focused mostly on domestic or national issues of justice, might be applied to questions of international justice as well. Others sought to extend his theory’s set of political principles, while still others probed the limits of Rawls’s epistemology and the narrowness of his focus on individuals. A decade after A Theory of Justice appeared, Forrester notes, 2,512 books and articles had been published engaging with its central claims.

With its doctrine of fairness, A Theory of Justice transformed political philosophy. The English historian Peter Laslett had described the field as “dead” in 1956; with Rawls’s book that changed almost overnight. Now philosophers were arguing about the nature of Rawlsian principles and their implications—and for that matter were once again interested in matters of political and economic justice. Rawls’s terms became lingua franca: Many considered how his arguments, focused mostly on domestic or national issues of justice, might be applied to questions of international justice as well. Others sought to extend his theory’s set of political principles, while still others probed the limits of Rawls’s epistemology and the narrowness of his focus on individuals. A decade after A Theory of Justice appeared, Forrester notes, 2,512 books and articles had been published engaging with its central claims.