Category: Archives

We Eat at The Worst Michelin Starred Restaurant, Ever

Geraldine DeRuiter in The Everywhereist:

There is something to be said about a truly disastrous meal, a meal forever indelible in your memory because it’s so uniquely bad, it can only be deemed an achievement. The sort of meal where everyone involved was definitely trying to do something; it’s just not entirely clear what.

There is something to be said about a truly disastrous meal, a meal forever indelible in your memory because it’s so uniquely bad, it can only be deemed an achievement. The sort of meal where everyone involved was definitely trying to do something; it’s just not entirely clear what.

I’m not talking about a meal that’s poorly cooked, or a server who might be planning your murder—that sort of thing happens in the fat lump of the bell curve of bad. Instead, I’m talking about the long tail stuff – the sort of meals that make you feel as though the fabric of reality is unraveling. The ones that cause you to reassess the fundamentals of capitalism, and whether or not you’re living in a simulation in which someone failed to properly program this particular restaurant. The ones where you just know somebody’s going to lift a metal dome off a tray and reveal a single blue or red pill.

More here.

2021 research reinforced that mating across groups drove human evolution

Bruce Bower in Science News:

A long-standing argument that Homo sapiens originated in East Africa before moving elsewhere and replacing Eurasian Homo species such as Neandertals has come under increasing fire over the last decade. Research this year supported an alternative scenario in which H. sapiens evolved across vast geographic expanses, first within Africa and later outside it.

A long-standing argument that Homo sapiens originated in East Africa before moving elsewhere and replacing Eurasian Homo species such as Neandertals has come under increasing fire over the last decade. Research this year supported an alternative scenario in which H. sapiens evolved across vast geographic expanses, first within Africa and later outside it.

The process would have worked as follows: Many Homo groups lived during a period known as the Middle Pleistocene, about 789,000 to 130,000 years ago, and were too closely related to have been distinct species. These groups would have occasionally mated with each other while traveling through Africa, Asia and Europe. A variety of skeletal variations on a human theme emerged among far-flung communities. Human anatomy and DNA today include remnants of that complex networking legacy, proponents of this scenario say.

More here.

India and Pakistan can achieve peace ‘by pieces’

Kanti Bajpai in This Week in Asia:

India and Pakistan have an impressive record of cooperation and peace initiatives. Virtually every bilateral problem they had before 1964 – except Kashmir – was solved diplomatically, including a landmark 1960 agreement on sharing the waters of the Indus River that both have since honoured, even in wartime.

India and Pakistan have an impressive record of cooperation and peace initiatives. Virtually every bilateral problem they had before 1964 – except Kashmir – was solved diplomatically, including a landmark 1960 agreement on sharing the waters of the Indus River that both have since honoured, even in wartime.

The two even came close to reaching a solution on Kashmir through bilateral talks and the United Nations, but negotiations that involved prominent Kashmiri leader Sheikh Abdullah were abandoned following the death of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, in 1964.

Since then, India and Pakistan have gone to war three times – in 1965, 1971, and 1999 – and had several more scares: in 1986-87, 1990, 2001-2, 2008, and most recently, after 2019’s Pulwama terrorist attack in Kashmir that prompted Indian air strikes on Balakot in retaliation. However, the two sides have also signed peace treaties and agreements: in Tashkent, after the 1965 war; and in Simla, after the 1971 war. When tensions ran high after their respective nuclear tests in 1998, the two signed the Lahore Declaration, which included understandings on nuclear controls, in February 1999.

More here.

Evelyn Waugh BBC Interview from 1953

Wednesday Poem

Atlantis

… Everything that has been said for several centuries

is swept away by my hands and hurled through high windows

into a big hole my father calls heaven but I call the sky.

He looked angrily at me because I swore the human soul

was smaller and forlorn as any 8 oz. tin you pay

half-price for at the Railroad Salvage Grocery Store.

… That was the night I thought he’d never learn

and I made foolish jokes about the boulevard in Minneapolis

where we both sat in darkness, watching yards where shadows

crawled between the bungalows like creatures from another world

and all the mothers who would never learn hung loads

of white shirts and nighties like ghosts who are waiting

… for Christ to return. I was 21 years old.

Already I had said too much: an immigrant from Norway, Michigan,

my father often spoke about another Norway where the sun

rose once but never set. This world couldn’t be your first,

he said, and by calling my ideas “wise” he shut me up. Age

21, my father thought that what his father thought

… was ridiculous, and railroaded here

to find another Michigan where he was sure silence had

the last word. Where he and his son could sit in darkness

swapping silences until between us we produced a third and final

silence big enough to house the wild inhabitants and keep alive

the kingdom of a sunken island we could swim to, should it rise.

by John Engman

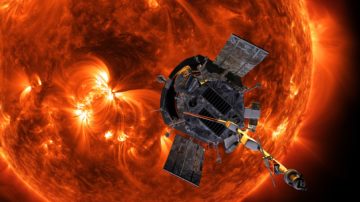

NASA spacecraft ‘touches’ the Sun for the first time ever

Alexandra Witze in Nature:

A NASA spacecraft has entered a previously unexplored region of the Solar System — the Sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona. The long-awaited milestone, which happened in April but was announced on 14 December, is a major accomplishment for the Parker Solar Probe, a craft that is flying closer to the Sun than any mission in history. “We have finally arrived,” said Nicola Fox, director of NASA’s heliophysics division, located at the agency’s headquarters in Washington DC. “Humanity has touched the Sun.”

A NASA spacecraft has entered a previously unexplored region of the Solar System — the Sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona. The long-awaited milestone, which happened in April but was announced on 14 December, is a major accomplishment for the Parker Solar Probe, a craft that is flying closer to the Sun than any mission in history. “We have finally arrived,” said Nicola Fox, director of NASA’s heliophysics division, located at the agency’s headquarters in Washington DC. “Humanity has touched the Sun.”

She and other team members spoke during a press conference at this week’s American Geophysical Union meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana. A paper describing the findings appears in Physical Review Letters1.

In many ways the Parker Solar Probe is a counterpoint to NASA’s twin Voyager spacecraft. In 2012, Voyager 1 travelled so far from the Sun that it became the first mission to leave behind the region of space dominated by the solar wind — the energetic flood of particles coming from the Sun. By contrast, the Parker probe is flying ever closer towards the heart of the Solar System, head-on into the solar wind and into our star’s atmosphere. With this new front-row seat scientists can explore some of the biggest unanswered questions about the Sun, such as how it generates the solar wind and how its corona gets heated to temperatures more extreme than those on the Sun’s surface.

“This is a huge milestone,” says Craig DeForest, a solar physicist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, who is not involved with the mission. Flying into the solar corona represents “one of the last great unknowns”, he says.

More here.

Why festive gatherings can be so toxic

David Robson in BBC:

“A happy family,” so the saying goes, “is but an earlier heaven” – which must surely make an unhappy family a living hell. As we enter the holiday season, many of us will be steeling ourselves for potential tension and argument. Whether it’s quiet disapproval over the quality of the cooking, a simmering resentment over alleged favouritism, or a fierce argument about our political and social values, family gatherings often bring out the worst in us. That’s if we choose to see our families at all – for many, there is no choice but to spend the holidays apart.

“A happy family,” so the saying goes, “is but an earlier heaven” – which must surely make an unhappy family a living hell. As we enter the holiday season, many of us will be steeling ourselves for potential tension and argument. Whether it’s quiet disapproval over the quality of the cooking, a simmering resentment over alleged favouritism, or a fierce argument about our political and social values, family gatherings often bring out the worst in us. That’s if we choose to see our families at all – for many, there is no choice but to spend the holidays apart.

While family strife may be a source of entertainment in dramas like Succession, the real-life consequences are no joke. “A really common consequence of estrangement is feeling isolated,” in addition to feelings of shame and being judged, says Lucy Blake, a developmental psychologist at the University of the West of England and author of the forthcoming book No Family Is Perfect: A Guide to Embracing the Messy Reality. There is no easy cure to heal fractured relationships. But a better understanding of our family dynamics can help prepare us for the inevitable flashpoints and reveal ways to cope with the stress.

More here.

Tuesday, December 14, 2021

Book review: The Rise of English, by Rosemary Salomone

Stan Carey in Sentence first:

For much of the previous millennium, a pidgin language was used around the Mediterranean for trading, diplomatic, and military purposes. Based originally on Italian and Occitano-Romance languages, it had indirect ties to the Germanic Franks and thus gained the term lingua franca.

For much of the previous millennium, a pidgin language was used around the Mediterranean for trading, diplomatic, and military purposes. Based originally on Italian and Occitano-Romance languages, it had indirect ties to the Germanic Franks and thus gained the term lingua franca.

Nowadays that phrase tends to be applied to Latin or English. Latin’s time as the default international language of learning ended long ago; English’s status as a lingua franca is still broader but very much in flux – and politically fraught, simultaneously uniting and dividing the world.

Tackling this topic is a new book, The Rise of English: Global Politics and the Power of Language, by Rosemary Salomone, a linguist and law professor in New York. Her impressive book (sent to me by OUP for review) does much to clarify the forces behind English’s position as a lingua franca and what the future might hold.

Having a lingua franca brings great benefits for travel, business, politics, and research: witness the speed at which Covid-19 vaccines were developed through international scientific collaboration. But English’s primacy rests on centuries of violence and exploitation. The power dynamics have shifted but remain unbalanced and entangled with complex threads of post-colonial identity.

More here.

The Omicron Question

Tomas Pueyo in Uncharted Territories:

There’s been a lot of great coverage of Omicron so far, but with the data we have, we can’t change our behavior at all. It’s not actionable. We’re missing one fundamental piece of information. It’s the Omicron question. This article will look at what we know so far to zero in on that big question.

There’s been a lot of great coverage of Omicron so far, but with the data we have, we can’t change our behavior at all. It’s not actionable. We’re missing one fundamental piece of information. It’s the Omicron question. This article will look at what we know so far to zero in on that big question.

There are two numbers that matter in epidemiology: the transmission rate and the fatality rate. The transmission rate tells you how many people are likely going to catch a virus, and how hard it will be to fight it. Once you catch it, the fatality rate tells you how bad it will be.

There’s an additional factor that matters: The Scary Virus Paradox. There’s an interaction between these two: a virus with high transmission rates but low fatality rates might end up killing more people than if the virus has higher fatality rates.

More here.

Pfizer’s Covid pill remains 89% effective in final analysis

Matthew Herper in Stat:

Paxlovid, Pfizer’s pill to treat Covid-19, retained its 89% efficacy at preventing hospitalization and death in the full results of a study of 2,246 high-risk patients, the company said Tuesday.

Paxlovid, Pfizer’s pill to treat Covid-19, retained its 89% efficacy at preventing hospitalization and death in the full results of a study of 2,246 high-risk patients, the company said Tuesday.

In early November, Pfizer had released interim results from the first 1,219 patients in the study. But another oral antiviral targeting Covid, from Merck and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, had seen estimates of its efficacy at preventing hospitalization drop from 50% to 30% between an interim result and a final one. A panel of experts advising the Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 30 recommended 13-11 that the Merck pill, molnupiravir, should be authorized for emergency use. The FDA has not announced a decision.

The oral medicines are seen as important because they could be much easier to deliver to infected people than existing drugs like monoclonal antibodies, which must be infused intravenously or injected.

More here.

Abdulrazak Gurnah Nobel Lecture

Tuesday Poem

My Friends the Pigeons

The American Experiment has entered

yet another critical phase.

My friends the pigeons, who rent

a ledge in the nine hundred block

of St. Louis, seem painfully aware of this.

I hope I am not merely projecting

my own dread onto them, but if I am

I do so with trepidation,

for pigeons are, by their very nature,

conduits of urban grief, though if

studied with an open, critical mind,

refract anemic sentiments. Oh sage

pigeons of the nine hundred block

of St. Louis Street . . . Will the crowds

cease to laugh at them?

A blight on the day the happy crowds

no longer laugh at them!

A blight on the idiocy of the Christian Right!

I have watched them on television

and shivered with grief.

They are forcing me to embrace

what otherwise I might shun,

such as ugly, mite-infested pigeons,

surrogate angels for those

never told their bodies were evil.

I thank my sweet, dead mother

for never telling me my body was evil,

and for laying a big, dirty feather

on my pillow one Christmas Eve.

by Richard Katrovas

from New American Poets of the ‘90s

publisher, David R. Godine, 1991

What we don’t know about OCD

Eleanor Cummins in Vox:

At 13, Arnie got a paper route. The work troubled him, however — and not in the usual way a kid might worry about their first adult responsibility. He could never be sure the papers had actually been delivered. “After Arnie had finished a block, he had to go back to be sure that there was a paper on each and every doorstop,” Judith L. Rapoport wrote in The Boy Who Couldn’t Stop Washing, her 1989 bestseller about treating people with obsessive compulsive disorder, or OCD. “As soon as he had checked it, and turned to face the new work, the feeling came over him: ‘I had better make sure.’” Around and around he’d go, unable to break the cycle.

At 13, Arnie got a paper route. The work troubled him, however — and not in the usual way a kid might worry about their first adult responsibility. He could never be sure the papers had actually been delivered. “After Arnie had finished a block, he had to go back to be sure that there was a paper on each and every doorstop,” Judith L. Rapoport wrote in The Boy Who Couldn’t Stop Washing, her 1989 bestseller about treating people with obsessive compulsive disorder, or OCD. “As soon as he had checked it, and turned to face the new work, the feeling came over him: ‘I had better make sure.’” Around and around he’d go, unable to break the cycle.

Arnie’s case was one of dozens of stories that Rapoport, a child psychiatrist, recounted in her book, one of the first accessible accounts of the disorder written from a doctor’s perspective. As Arnie grew older, his preoccupations began to morph. He never felt as though he could shower or dress “right.” His days were disrupted by violent thoughts about hurting his family members. In his 20s, he got a job in a shoe store but felt compelled, when sorting shoes by size and style, to never repeat any action six or 13 times. On some level, Arnie probably knew the papers had been delivered successfully, that he wasn’t going to kill his family, and that the storeroom was sufficiently ordered. But, on another level, Rapoport wrote, he just couldn’t be sure.

For most of the 20th century, OCD — defined by obsessive thoughts, compulsive rituals, or a combination of the two — was considered a rare and incurable illness. But starting in the 1980s, researchers like Rapoport began to find that the “doubting disease,” as some patients called it, was much more common and more responsive to treatment than previously imagined. Today, studies indicate about 2.3 percent of American adults have had or currently have OCD. For many, the disorder can severely affect quality of life: About half of those with OCD experience serious impairment as obsessions and compulsions take time away from work, relationships, and even more basic functions like dressing and eating.

More here.

Joanna Hogg and the Art of Life

Devika Girish at The Nation:

When does a life become a story, a narrative legible to those outside it? This question trills at the heart of Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir (2019) and the new The Souvenir Part II, a two-part film à clef constructed like a precarious house of cards: memories, texts, and ephemera from a life, stacked carefully one upon another in the hope that they hold their shape. The films take their names from Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s rococo 18th-century painting The Souvenir, which shows a woman in a lustrous pink gown carving an initial into a tree; a letter, presumably from her lover, lies on the ground by her feet. It’s an image of willful alchemy—of turning a memory, a feeling, into an object and event in the exterior world. The painting itself reifies a scene in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s epistolary 1761 novel Julie; or, The New Heloise, about the mercurial passions between a married woman and her former flame—which in turn draws on the medieval tale of the French nun Héloïse d’Argenteuil and, likely, Rousseau’s own romantic entanglements. To this series of artistic transfigurations, Hogg adds her own, constellating personal references as she reconstructs her youth: the 1938 song “A Souvenir of Love” by Jessie Matthews, the films of Powell and Pressburger, period fashion from Manolo Blahnik and Yohji Yamamoto, letters from Hogg’s former lover, 16-millimeter pictures she took in the 1980s. Together, all these objects and invocations comprise a life of the mind, an intellectual history assembled in the hope that it might represent something more than just that: the haphazard accumulations of one’s time on earth.

When does a life become a story, a narrative legible to those outside it? This question trills at the heart of Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir (2019) and the new The Souvenir Part II, a two-part film à clef constructed like a precarious house of cards: memories, texts, and ephemera from a life, stacked carefully one upon another in the hope that they hold their shape. The films take their names from Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s rococo 18th-century painting The Souvenir, which shows a woman in a lustrous pink gown carving an initial into a tree; a letter, presumably from her lover, lies on the ground by her feet. It’s an image of willful alchemy—of turning a memory, a feeling, into an object and event in the exterior world. The painting itself reifies a scene in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s epistolary 1761 novel Julie; or, The New Heloise, about the mercurial passions between a married woman and her former flame—which in turn draws on the medieval tale of the French nun Héloïse d’Argenteuil and, likely, Rousseau’s own romantic entanglements. To this series of artistic transfigurations, Hogg adds her own, constellating personal references as she reconstructs her youth: the 1938 song “A Souvenir of Love” by Jessie Matthews, the films of Powell and Pressburger, period fashion from Manolo Blahnik and Yohji Yamamoto, letters from Hogg’s former lover, 16-millimeter pictures she took in the 1980s. Together, all these objects and invocations comprise a life of the mind, an intellectual history assembled in the hope that it might represent something more than just that: the haphazard accumulations of one’s time on earth.

more here.

BFI At Home | Filmmakers in Focus: Joanna Hogg

Modernity And The Fall

Caitrin Keiper at The New Atlantis:

In Susanna Clarke’s fantasy novel Piranesi, we meet an exceptionally innocent narrator who dates his life from a sublime encounter he has with an albatross. As the bird comes swooping toward him, he has a vision that they could merge into a being he knows of but has never seen — “an Angel!” — and imagines how he will fly through the world with “messages of Peace and Joy.” When he and the albatross do not become one, he instead offers it a gracious welcome, and helps it gather materials for a warm, dry nest. He sacrifices his own resources to do this, “but what is a few days of feeling cold compared to a new albatross in the World?” From this point on, his detailed notebooks refer to “the Year the Albatross came to the South-Western Halls.”

In Susanna Clarke’s fantasy novel Piranesi, we meet an exceptionally innocent narrator who dates his life from a sublime encounter he has with an albatross. As the bird comes swooping toward him, he has a vision that they could merge into a being he knows of but has never seen — “an Angel!” — and imagines how he will fly through the world with “messages of Peace and Joy.” When he and the albatross do not become one, he instead offers it a gracious welcome, and helps it gather materials for a warm, dry nest. He sacrifices his own resources to do this, “but what is a few days of feeling cold compared to a new albatross in the World?” From this point on, his detailed notebooks refer to “the Year the Albatross came to the South-Western Halls.”

The man called Piranesi (though he correctly senses that is not really his name) is one of only two human inhabitants in what he calls the House, a labyrinth of marble halls and ocean life and statues of people and nature and legend. Piranesi’s many energies are devoted to exploring and documenting the House with care.

more here.

Sunday, December 12, 2021

Treason of the Intellectuals

Mark Lilla in Tablet:

Certain books never live up to their memorable titles. Others do, but not in the way their authors might have anticipated. Julien Benda’s The Treason of the Intellectuals, an essential intervention in 20th-century debates about intellectual responsibility, is the second sort of book. Cast into the agitated waters of European politics between the two world wars, it still floats ashore every decade or so, attracting readers with its stirring call to the independent life of the mind, free from the lures of power and authority. It is essential reading. Ever since the book’s publication in 1927, its argument has been taken up by writers of very different political stripes in very different historical circumstances. In the 1930s communist intellectuals denounced their fascist counterparts as traitors to the truth; liberals levied the same charge against communists and fellow travelers during the Cold War, only to find themselves then put in the dock by progressives and neoconservatives and now populists. Treason is one of those books that serve both as a lens for discerning the present and a mirror reflecting the image of those who appeal to it.

Certain books never live up to their memorable titles. Others do, but not in the way their authors might have anticipated. Julien Benda’s The Treason of the Intellectuals, an essential intervention in 20th-century debates about intellectual responsibility, is the second sort of book. Cast into the agitated waters of European politics between the two world wars, it still floats ashore every decade or so, attracting readers with its stirring call to the independent life of the mind, free from the lures of power and authority. It is essential reading. Ever since the book’s publication in 1927, its argument has been taken up by writers of very different political stripes in very different historical circumstances. In the 1930s communist intellectuals denounced their fascist counterparts as traitors to the truth; liberals levied the same charge against communists and fellow travelers during the Cold War, only to find themselves then put in the dock by progressives and neoconservatives and now populists. Treason is one of those books that serve both as a lens for discerning the present and a mirror reflecting the image of those who appeal to it.

The $11-billion Webb telescope aims to probe the early Universe

Alexandra Witze in Nature:

Lisa Dang wasn’t even born when astronomers started planning the most ambitious and complex space observatory ever built. Now, three decades later, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is finally about to launch, and Dang has scored some of its first observing time — in a research area that didn’t even exist when it was being designed.

Lisa Dang wasn’t even born when astronomers started planning the most ambitious and complex space observatory ever built. Now, three decades later, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is finally about to launch, and Dang has scored some of its first observing time — in a research area that didn’t even exist when it was being designed.

Dang, an astrophysicist and graduate student at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, will be using the telescope, known as Webb for short, to stare at a planet beyond the Solar System. Called K2-141b, it is a world so hot that its surface is partly molten rock. She is one of dozens of astronomers who learnt in March that they had won observing time on the telescope. The long-awaited Webb — a partnership involving NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) — is slated to lift off from a launch pad in Kourou, French Guiana, no earlier than 22 December.

More here.

How—and Why—America Criminalizes Poverty

Tony Messenger in Literary Hub:

Nearly every state in the country has a statute—often called a “board bill” or “pay-to-stay” bill—that charges people for time served. In Missouri and Oklahoma—and in states on both coasts and in the Deep South—these pay-to-stay bills follow defendants arrested initially for small offenses like petty theft or falling behind in child support. Nearly 80 percent of these defendants live below the federal poverty line, meaning they make less than $12,880 a year if they are single, or $21,960 if they are a family of three.

Nearly every state in the country has a statute—often called a “board bill” or “pay-to-stay” bill—that charges people for time served. In Missouri and Oklahoma—and in states on both coasts and in the Deep South—these pay-to-stay bills follow defendants arrested initially for small offenses like petty theft or falling behind in child support. Nearly 80 percent of these defendants live below the federal poverty line, meaning they make less than $12,880 a year if they are single, or $21,960 if they are a family of three.

They are the working poor: getting by on minimum wage jobs at the local dollar store; seasonal construction workers who get roofing jobs after tornado season; or, like Bergen, they are unemployed, unable to escape the combination of drug offenses and a criminal justice system that follows them everywhere. In some places, like Rapid City, South Dakota, the charges for jail time are small, $6 a day; in other places, like Riverside County, California, they have been as high as $142 a day. For people of little means, these court debts are an albatross they cannot escape or ignore.

More here.