Category: Archives

Radu Lupu (1945 – 2022) Pianist

Sunday Poem

From:

Five Villanelles

The crack is moving down the wall.

Defective plaster isn’t all the cause.

We must remain until the roof falls in.

It’s mildly cheering to recall

That every building has its little flaws.

The crack is moving down the wall.

Here in the kitchen, drinking gin,

We can accept the damndest laws.

We must remain until the roof falls in.

And though there’s no one here at all,

One searches every room because

The crack is moving down the wall.

Repairs? But how can one begin?

The lease has warnings buried in each clause.

We must remain until the roof falls in.

These nights one hears a creaking in the hall,

The kind of thing that gives one pause.

The crack is moving down the wall.

We must remain until the roof falls in.

by Weldon Kees

from Strong Measures

Harper Collins, 1986

Jimmy Wang Yu (1943 – 2022) Kung Fu Actor

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q1ye60-Zbyw&ab_channel=jimmywangyucollection

How to Inhabit the Word

Nina Li Coomes in Guernica:

Wet earth. Loam. Bitter ash, brine on the wind. The unfurling of cedar, a smell that takes me out of this place and back to bathtubs in Japan; a portal of a scent, sacred and red. These are the smells of the Pacific Northwest wood from where I write this. In the daytime, as light pours around the unfamiliar landscape, I think of it as a new smell, something to gulp. But last night, clambering up the half-hill toward the cottage where I am staying, I took another breath and was suddenly tearful. The damp soil transformed into the smell of my Jiji, wood-smoke mimicking cigarette-smoke lingering in the folds of his shirt.

Wet earth. Loam. Bitter ash, brine on the wind. The unfurling of cedar, a smell that takes me out of this place and back to bathtubs in Japan; a portal of a scent, sacred and red. These are the smells of the Pacific Northwest wood from where I write this. In the daytime, as light pours around the unfamiliar landscape, I think of it as a new smell, something to gulp. But last night, clambering up the half-hill toward the cottage where I am staying, I took another breath and was suddenly tearful. The damp soil transformed into the smell of my Jiji, wood-smoke mimicking cigarette-smoke lingering in the folds of his shirt.

To read In Sensorium is to be made as aware of the sensuousness of place, time, and body, as I am now aware of all the smells around me. When I tried to read your essays back in my Chicago apartment, I found myself frustrated and lost in the swirling meditations. I was distracted and fractured, couldn’t slow down to digest. But here, alone in the deep quiet with nothing to do but move my body through the day, your prose has opened up for me. Or rather, I have opened up to your prose.

More here.

Work is broken. Can we fix it?

The Team at Vox:

“We often begin to understand things only after they break down. This is why, in addition to being a worldwide catastrophe, the pandemic has been a large-scale philosophical experiment,” Jonathan Malesic, author of The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives, writes in this month’s issue of the Highlight.

“We often begin to understand things only after they break down. This is why, in addition to being a worldwide catastrophe, the pandemic has been a large-scale philosophical experiment,” Jonathan Malesic, author of The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives, writes in this month’s issue of the Highlight.

What has broken down, of course, is work, and what American workers, policymakers, and employers now can see plainly are the countless truths the pandemic laid bare: that productivity does not actually require an air-polluting, hourlong daily drive to a soulless downtown office building; that a fair and just society ought not put the poorest, most vulnerable Americans in danger in the name of capitalism; that the entire economy might just be held together by a rapidly dwindling sea of people — child care workers — earning roughly $13 an hour, with no benefits.

In this month’s Future of Work issue, the Highlight and Recode teamed up to explore the precarity faced by those workers whom the Great Resignation did not offer much in the way of increased power or security. We look beyond simply what is broken about their working lives, asking policy experts and workers themselves: What could make work better?

More here.

Saturday, April 23, 2022

Abolition Democracy’s Forgotten Founder

Robin D. G. Kelley in Boston Review:

Robin D. G. Kelley in Boston Review:

Nearly every activist I encounter these days identifies as an abolitionist. To be sure, movements to abolish prisons and police have been around for decades, popularizing the idea that caging and terrorizing people makes us unsafe. However, the Black Spring rebellions revealed that the obscene costs of state violence can and should be reallocated for things that do keep us safe: housing, universal healthcare, living wage jobs, universal basic income, green energy, and a system of restorative justice. As abolition recently became the new watchword, everyone scrambled to understand its historical roots. Reading groups popped up everywhere to discuss W. E. B. Du Bois’s classic, Black Reconstruction in America (1935), since he was the one to coin the phrase “abolition democracy,” which Angela Y. Davis revived for her indispensable book of the same title.

I happily participated in Black Reconstruction study groups and public forums meant to divine wisdom for our current movements. But I often wondered why no one was scrambling to resurrect T. Thomas Fortune’s Black and White: Land, Labor, and Politics in the South, published in 1884. After all, it was Fortune who wrote: “The South must spend less money on penitentiaries and more money on schools; she must use less powder and buckshot and more law and equity; she must pay less attention to politics and more attention to the development of her magnificent resources.”

More here.

The French Far Right Comes on Little Cat Feet

James McAuley in The New Yorker (Photograph by Rit Heize / Xinhua / Getty):

James McAuley in The New Yorker (Photograph by Rit Heize / Xinhua / Getty):

In the early spring of 2017, before France’s previous Presidential election, I took a taxi from my apartment in Paris to Saint-Cloud, a wealthy suburb to the west of the city. I remember the feeling of dread as the car crossed the Seine, the quaint church set into a hillside overlooking the urban sprawl below. I was a twenty-eight-year-old reporter, and Jewish, about to visit the home of Jean-Marie Le Pen, one of the country’s most notorious Holocaust deniers and far-right agitators.

Jean-Marie’s daughter, Marine, was running in the French Presidential election for the second time that year, and I was there to profile him for the Washington Post. On April 24th, she will again face off against Emmanuel Macron, in the final round of the vote. The two sparred in a lengthy debate on April 20th, during which Macron hammered Marine for her admiration of Vladimir Putin and reliance on a Russian bank, and she attacked him for ignoring the plight of ordinary citizens. The far right has not been this close to power in France since 1944. Marine has styled herself as a candidate of almost grandmotherly compassion, focussing on the rising cost of living and posing for photos with her cats. Although she is likely to lose, she has already won the battle for legitimacy: polls project her winning forty-four per cent of the vote, which would be her highest share in any of her three Presidential campaigns. She is increasingly popular with working-class and lower-middle-class voters, who say that she has listened to their economic concerns while Macron, preoccupied by the war in Ukraine, has barely bothered to campaign.

More here.

Economic War and the Commodity Shock

Alex Yablon , Nicholas Mulder, Javier Blas in Phenomenal World:

Alex Yablon , Nicholas Mulder, Javier Blas in Phenomenal World:

The war in Ukraine has unleashed both geopolitical and economic strife, and nowhere is the latter clearer than in the volatile commodities market. Commodities prices have fluctuated wildly since the Russian invasion began and the US-led coalition retaliated with extraordinary sanctions on Russia’s financial system and trade networks. Few outside the American intelligence community expected Russia to invade; even fewer expected Russia’s rivals to so forcefully and swiftly confront the belligerent power with such a sweeping raft of economic sanctions.

While diplomatic relations with Russia have been deteriorating for more than a decade, the Western attempt to sever all economic relations with the country may mark a historical turning point. For the first time in decades, the world finds itself in an economic crisis originating not with the financial sector, but in the real economy. The economic disruptions of war itself and the breakdown of financial and trade ties with Russia—a global commodities powerhouse—have had repercussions around the world. Rising fertilizer prices are threatening the viability of Peruvian rice farms. The loss of Ukrainian neon production is driving up costs for Taiwanese chip manufacturers, already squeezed for capacity in recent years. The blockade at the port of Odessa threatens a general food crisis for the Middle East and North Africa. And the metals exchanges are in disarray as pricing chaos pushes margin calls ever higher.

More here.

Romanticism – The Lasting Effects (Isaiah Berlin 1965)

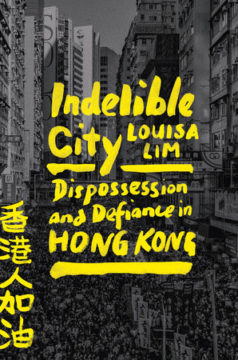

Louisa Lim’s “Indelible City”

Jennifer Szalia at the NYT:

In “Indelible City,” Louisa Lim charts how her own identity as a Hong Konger had never been so clear until China’s brutal attempts to crush pro-democracy protests in 2019. She had been feeling increasingly alienated from a densely populated place where extreme inequality, soaring costs and shrinking real estate made “the very act of living” — even for “still very privileged” people like her — completely exhausting. Lim’s experience as a reporter amid a swell of protesters changed that. She could feel her face flush and her throat well up — not from the tear gas, of which there was plenty, but from a surge of emotions: “I’d fallen in love with Hong Kong all over again.”

In “Indelible City,” Louisa Lim charts how her own identity as a Hong Konger had never been so clear until China’s brutal attempts to crush pro-democracy protests in 2019. She had been feeling increasingly alienated from a densely populated place where extreme inequality, soaring costs and shrinking real estate made “the very act of living” — even for “still very privileged” people like her — completely exhausting. Lim’s experience as a reporter amid a swell of protesters changed that. She could feel her face flush and her throat well up — not from the tear gas, of which there was plenty, but from a surge of emotions: “I’d fallen in love with Hong Kong all over again.”

Needless to say, this is an unapologetically personal book. For Lim, who worked as a correspondent for the BBC and NPR, the turmoil in Hong Kong made it ever harder “to safeguard my professional neutrality.”

more here.

A Conversation With Nan Z. Da

Nan Z. Da and Jessica Swoboda at The Point:

JS: What do you see as the differences between academic writing and other forms of writing?

JS: What do you see as the differences between academic writing and other forms of writing?

ND: There’s an oft-quoted line by Niklas Luhmann, an acute understanding of the endgame of social evolution in modernity. He posits that “humans cannot communicate; not even their brains can communicate; not even their conscious minds can communicate. Only communication can communicate.” You’re not supposed to think of this as writing advice. Nonetheless, things have to be primed for communication.

Academic writing has to look different than nonfiction writing, has to look different than journalism, and so forth, for much the same reason that interdisciplinarity means nothing if disciplines don’t have operational closure, don’t have integrity. You have to have categorical and systemic partitioning, even hard generic distinctions, in order to see curious crossings.

more here.

Saturday Poem

The Accolade of the Animals

All those he never ate

appeared to Bernard Shaw

single file in his funeral

procession as he lay abed

with a cracked infected bone

from falling of his bicycle.

They stretched from Hampton Court

downstream to Piccadilly

against George Bernard’s pillow

paying homage to the flesh

of man unfleshed by carnage.

Just shy of a hundred years

of pullets, laying hens

no longer laying, ducks, turkeys,

pigs and piglets, old milk cows,

anemic vealers, grain-fed steer,

the annual Easter lambkin,

the All Hallows’ mutton

ring-neck pheasant, deer,

bags of hare unsnared,

rosy trout and turgid carp,

tail-walking like a sketch by Tenniel.

What a cortege it was:

the smell of hay in his nose,

the pungencies of the barn,

the courtyard cobbles slicked

with wet, How we carnivores

suffer by comparison

in the jail of our desires

salivating at the smell of char

who will not live on fruits

and greens and grains alone

so long a life, so sprightly, so cocksure.

by Maxine Kumin

from Nurture

Viking Books, 1989

How Rumi Can Explain Why Nirvana is Samsara

From Networkologies:

The notion of fana’, commonly translated from Arabic as annihilation or obliteration, provides a potential point of contact between Sufi practices and Buddhist notions of nirvana, a word which, in Sanskrit, derives from the type of extinction one sees when one snuffs out the flame of a candle. Are there similarities between these notions, ones which might be constructed without radically oversimplifying the issues at hand? On the surface, ‘annihilation’ and ‘extinction’ might seem similar. But what a Buddhist extinguishes is craving, while what a Sufi annihilates is themselves before God. And yet, as will become clear, there are crucial parallels that can help us see the ways in which what these traditions have to teach us today have crucial resonances within and through their very real differences.

The notion of fana’, commonly translated from Arabic as annihilation or obliteration, provides a potential point of contact between Sufi practices and Buddhist notions of nirvana, a word which, in Sanskrit, derives from the type of extinction one sees when one snuffs out the flame of a candle. Are there similarities between these notions, ones which might be constructed without radically oversimplifying the issues at hand? On the surface, ‘annihilation’ and ‘extinction’ might seem similar. But what a Buddhist extinguishes is craving, while what a Sufi annihilates is themselves before God. And yet, as will become clear, there are crucial parallels that can help us see the ways in which what these traditions have to teach us today have crucial resonances within and through their very real differences.

How does one achieve fana’? One remembers, and this remembering, or dhikr, often also translated from Arabic as recitation, can take many forms. Essentially, one puts oneself into sync with some original pronouncement made by God, for the universe is the speech of God, God speaks the world into being (according to the Qu’ran, by the word “Be!”), and when we remember one of God’s actions, we do so by having our action in some way coming into sync with God’s, by repeating this aspect of his recitation. And since God is beyond time and space, while we are not, God’s action is always before, during, and after ours, our actions are never initiatory, but merely remembrances of God, the one who brought about all that is, even that which is in the future. All potentials are in God, as we were, and will be.

More here.

Nicholas Kristof’s Botched Rescue Mission

Olivia Nuzzi in Intelligencer:

By the time I arrived in Yamhill, Oregon, Nicholas Kristof’s political career had already ended in a face-plant. “I didn’t feel any burning ambition to be a politician whatsoever,” he told me. Good thing. From start to finish, from his decision to quit the New York Times to the state Supreme Court decision that ruled him ineligible to hold the office, his campaign for governor lasted all of 114 days. Now he was no longer a columnist or a candidate, and about this outcome he claimed to be at peace.

By the time I arrived in Yamhill, Oregon, Nicholas Kristof’s political career had already ended in a face-plant. “I didn’t feel any burning ambition to be a politician whatsoever,” he told me. Good thing. From start to finish, from his decision to quit the New York Times to the state Supreme Court decision that ruled him ineligible to hold the office, his campaign for governor lasted all of 114 days. Now he was no longer a columnist or a candidate, and about this outcome he claimed to be at peace.

It was the afternoon of Friday, March 25, and the sun lit up the hills around the Kristof family estate, accessed via a winding road over rolling fields, past neighboring dairies and a sharp turn up a steep dirt road leading to a keypad-protected gate. In friendly Kristof fashion, a sign posted at the entrance welcomes guests in a loopy font that spells out the passcode.

A Pulitzer Prize winner once described as the conscience of a generation of journalists, Kristof devoted his life to chasing stories of poverty and genocide in places like Darfur and Sudan before epidemics of addiction and homelessness called his attention back to his home state. “I spent so much time reporting abroad in Afghanistan and Iraq and thinking this is really important and trying to convince people in the U.S. that this is important. And I deeply believe it was,” he told me. “But last time I calculated, every three weeks in the U.S., we were losing more Americans to drugs, alcohol, and suicide than Americans who died in 20 years of war in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

More here.

Friday, April 22, 2022

Artificial intelligence is creating a new colonial world order

Karen Hao in the MIT Technology Review:

Over the last few years, an increasing number of scholars have argued that the impact of AI is repeating the patterns of colonial history. European colonialism, they say, was characterized by the violent capture of land, extraction of resources, and exploitation of people—for example, through slavery—for the economic enrichment of the conquering country. While it would diminish the depth of past traumas to say the AI industry is repeating this violence today, it is now using other, more insidious means to enrich the wealthy and powerful at the great expense of the poor.

Over the last few years, an increasing number of scholars have argued that the impact of AI is repeating the patterns of colonial history. European colonialism, they say, was characterized by the violent capture of land, extraction of resources, and exploitation of people—for example, through slavery—for the economic enrichment of the conquering country. While it would diminish the depth of past traumas to say the AI industry is repeating this violence today, it is now using other, more insidious means to enrich the wealthy and powerful at the great expense of the poor.

I had already begun to investigate these claims when my husband and I began to journey through Seville, Córdoba, Granada, and Barcelona. As I simultaneously read The Costs of Connection, one of the foundational texts that first proposed a “data colonialism,” I realized that these cities were the birthplaces of European colonialism—cities through which Christopher Columbus traveled as he voyaged back and forth to the Americas, and through which the Spanish crown transformed the world order.

More here.

Biotech firm announces results from first US trial of genetically modified mosquitoes

Emily Waltz in Nature:

Researchers have completed the first open-air study of genetically engineered mosquitoes in the United States. The results, according to the biotechnology firm running the experiment, are positive. But larger tests are still needed to determine whether the insects can achieve the ultimate goal of suppressing a wild population of potentially virus-carrying mosquitoes.

Researchers have completed the first open-air study of genetically engineered mosquitoes in the United States. The results, according to the biotechnology firm running the experiment, are positive. But larger tests are still needed to determine whether the insects can achieve the ultimate goal of suppressing a wild population of potentially virus-carrying mosquitoes.

The experiment has been underway since April 2021 in the Florida Keys, a chain of tropical islands near the southern tip of Florida. Oxitec, which developed the insects, released nearly five million engineered Aedes aegypti mosquitoes over the course of seven months, and has now almost completed monitoring the release sites.

More here.

Strandbeest Evolution 2021

The Russo-Ukrainian War and Global Order

John M. Owen in The Hedgehog Review:

The war has exposed Russia as a conventional also-ran bristling with 4,500 nuclear warheads, but not a great power. The war has also unleashed a number of complications: it has heightened the dependency of Russia’s economy on energy exports; jeopardized those exports to the lucrative European market; affected Russia internally by making it more autocratic and opening a new brain drain; generated remarkable solidarity in the West, including a probable further expansion of NATO in the Nordic region and deployments of military assets to eastern members; and led those democracies to impose severe economic sanctions on Russia, including a freeze on Russia’s sovereign wealth deposits in their banks and a disabling of Russian banks from using the SWIFT system. Dozens of Western companies, under societal pressure, have closed down or suspended operations in Russia. (By “the West,” I mean, following convention, not only North America and Europe but also other wealthy democracies including Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, all of which thus far have joined the sanctions against Russia.)

The war has exposed Russia as a conventional also-ran bristling with 4,500 nuclear warheads, but not a great power. The war has also unleashed a number of complications: it has heightened the dependency of Russia’s economy on energy exports; jeopardized those exports to the lucrative European market; affected Russia internally by making it more autocratic and opening a new brain drain; generated remarkable solidarity in the West, including a probable further expansion of NATO in the Nordic region and deployments of military assets to eastern members; and led those democracies to impose severe economic sanctions on Russia, including a freeze on Russia’s sovereign wealth deposits in their banks and a disabling of Russian banks from using the SWIFT system. Dozens of Western companies, under societal pressure, have closed down or suspended operations in Russia. (By “the West,” I mean, following convention, not only North America and Europe but also other wealthy democracies including Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, all of which thus far have joined the sanctions against Russia.)

The war also has demonstrated that most of the rest of the world—that is, the great majority of the world’s population—is more ambivalent about the war than is the West. The war has put China on the spot.

More here.

Unbridled Romanticism – Fichte, Schelling, & Symbols (Isaiah Berlin 1965)