An Introduction to Some Poems

Look: no one ever promised for sure

that we would sing. We have decided

to moan. In a strange dance that

we don’t understand till we do it, we

have to carry on.

Just as in sleep you have to dream

the exact dream to round out your life,

so we have to live that dream into stories

and hold them close at you, close at the

edge we share, to be right.

We find it an awful thing to meet people,

serious or not, who have turned into vacant

effective people, so far lost that they

won’t believe their own feelings

enough to follow them out.

The authentic is a line from one thing

along to the next; it interests us.

strangely, it relates to what works,

but is not quite the same. It never

swerves for revenge,

Or profit, or fame: it holds

together something more than the world,

this line. And we are your wavery

efforts at following it. Are you coming?

Good: now it is time.

by William Stafford

from The Way It Is: New and Selected Poems

Graywolf Press, 1998

FOR THE PAST DECADE,

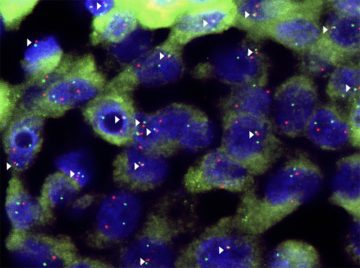

FOR THE PAST DECADE, When someone’s liver is infected with hepatitis B, damage increases over time, as long as the virus is active. The liver tissue thickens and forms scars (fibrosis), advancing to severe scarring called cirrhosis. In approximately one-third of people with hepatitis B infection, this then progresses to hepatocellular carcinoma, as the viral DNA inserts itself into liver cells, changing their function and allowing tumours to grow.

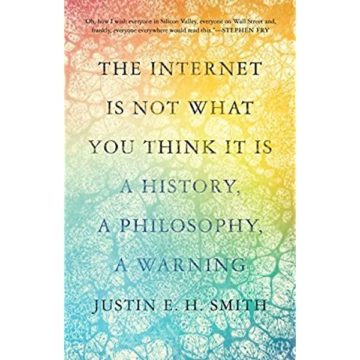

When someone’s liver is infected with hepatitis B, damage increases over time, as long as the virus is active. The liver tissue thickens and forms scars (fibrosis), advancing to severe scarring called cirrhosis. In approximately one-third of people with hepatitis B infection, this then progresses to hepatocellular carcinoma, as the viral DNA inserts itself into liver cells, changing their function and allowing tumours to grow. Yet this book could not be summarized as a jeremiad against cyberspace, because it, like most of Smith’s essays and scholarship, rarifies its subject through its author’s talent for synthesizing seemingly disparate ideas and endeavors. In building an alternative model of the internet, Smith transports his reader between discussions of Proust and 1940s hunting gadgetry; the signaling of sperm whales and the metaphysics of methyl jasmonate; Melanesian ritual masks and the Kuiper Belt; Norbert Wiener’s cybernetics and Grand Theft Auto; the nascent industry of “teledildonics” and the rueful poetics of railways; Kant’s epistemology and the pablum of Mark Zuckerberg. In a book that meditates upon networks, webs, and connections, Smith’s astounding range becomes something of a method for revealing the interconnectedness of everything between stars and modems.

Yet this book could not be summarized as a jeremiad against cyberspace, because it, like most of Smith’s essays and scholarship, rarifies its subject through its author’s talent for synthesizing seemingly disparate ideas and endeavors. In building an alternative model of the internet, Smith transports his reader between discussions of Proust and 1940s hunting gadgetry; the signaling of sperm whales and the metaphysics of methyl jasmonate; Melanesian ritual masks and the Kuiper Belt; Norbert Wiener’s cybernetics and Grand Theft Auto; the nascent industry of “teledildonics” and the rueful poetics of railways; Kant’s epistemology and the pablum of Mark Zuckerberg. In a book that meditates upon networks, webs, and connections, Smith’s astounding range becomes something of a method for revealing the interconnectedness of everything between stars and modems. There is something irresistible about John Keats’s poignantly brief life and his outsize greatness as an artist. That such a wealth of material about him exists—his own astonishing letters as well as reminiscences and diaries of his friends—means that there has never been a shortage of biographies. Vignettes began appearing soon after Keats’s death in 1821, with the first full biography, by Richard Monckton Milnes (a Victorian politician, failed suitor of Florence Nightingale, and avid collector of erotica), appearing in 1848. More recent lives of the poet include works by Amy Lowell (1924), Robert Gittings (1968), Andrew Motion (1997), and Nicholas Roe (2012), to name a few. Now the English literary journalist and biographer Lucasta Miller has added to the pile. She wrote her book, pegged to the 200th anniversary of Keats’s death, under pandemic lockdown in Hampstead, an area of London where the poet himself lived, a place still haunted by Keatsian associations.

There is something irresistible about John Keats’s poignantly brief life and his outsize greatness as an artist. That such a wealth of material about him exists—his own astonishing letters as well as reminiscences and diaries of his friends—means that there has never been a shortage of biographies. Vignettes began appearing soon after Keats’s death in 1821, with the first full biography, by Richard Monckton Milnes (a Victorian politician, failed suitor of Florence Nightingale, and avid collector of erotica), appearing in 1848. More recent lives of the poet include works by Amy Lowell (1924), Robert Gittings (1968), Andrew Motion (1997), and Nicholas Roe (2012), to name a few. Now the English literary journalist and biographer Lucasta Miller has added to the pile. She wrote her book, pegged to the 200th anniversary of Keats’s death, under pandemic lockdown in Hampstead, an area of London where the poet himself lived, a place still haunted by Keatsian associations. Before I begin, I would like to say a few words about the war in Ukraine. I unequivocally condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and applaud the Ukrainian peoples’ courageous resistance. I applaud the courage shown by Russian dissenters at enormous cost to themselves.

Before I begin, I would like to say a few words about the war in Ukraine. I unequivocally condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and applaud the Ukrainian peoples’ courageous resistance. I applaud the courage shown by Russian dissenters at enormous cost to themselves. I am an

I am an  “Ken’s fearless passion for justice, his courage and compassion towards the victims of human rights violations and atrocity crimes was not just professional responsibility but a personal conviction to him,” said Fatou Bensouda, former chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. “He has indeed been a great inspiration to me and my colleagues.”

“Ken’s fearless passion for justice, his courage and compassion towards the victims of human rights violations and atrocity crimes was not just professional responsibility but a personal conviction to him,” said Fatou Bensouda, former chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. “He has indeed been a great inspiration to me and my colleagues.” We see a pile of cloth in a barely lit room. We look, and we look some more, and might make out an ever-so-slight movement under the cloth, as if the object were breathing. Then wham: a walloping sound bursts the silence, the covers fall back, and Tilda Swinton rises into frame.

We see a pile of cloth in a barely lit room. We look, and we look some more, and might make out an ever-so-slight movement under the cloth, as if the object were breathing. Then wham: a walloping sound bursts the silence, the covers fall back, and Tilda Swinton rises into frame. Upon returning to Paris in the aftermath of the riots, Bourouissa began spending time in the banlieues with friends, who introduced him to more people who lived there. He eventually conscripted these figures, mostly men from immigrant backgrounds, as subjects for a series of staged photographs composed in the tradition of tableaux vivants, or living pictures—an uncanny arrangement that places ordinary people in relief against their normal environments, to an intimate yet estranging effect. The first of these staged pictures, “La fenêtre” (“The Window”), depicts two Black men captured mid-conversation, a shocking lime-green wall their background. The taut musculature of their torsos—one clothed, the other bare, a large tattoo sprawling across the curve of his back—is accentuated by the light streaming in through the titular window at top left, heightening the dramatic tension that pervades the scene. Here, the two figures stand in for the strained relations between the state and its frustrated poor, and between civil society and the immigrant class circumscribed to its périphérique—the name Bourouissa would later give to the series of photographs, after the circular highway separating Paris from its outer suburbs.

Upon returning to Paris in the aftermath of the riots, Bourouissa began spending time in the banlieues with friends, who introduced him to more people who lived there. He eventually conscripted these figures, mostly men from immigrant backgrounds, as subjects for a series of staged photographs composed in the tradition of tableaux vivants, or living pictures—an uncanny arrangement that places ordinary people in relief against their normal environments, to an intimate yet estranging effect. The first of these staged pictures, “La fenêtre” (“The Window”), depicts two Black men captured mid-conversation, a shocking lime-green wall their background. The taut musculature of their torsos—one clothed, the other bare, a large tattoo sprawling across the curve of his back—is accentuated by the light streaming in through the titular window at top left, heightening the dramatic tension that pervades the scene. Here, the two figures stand in for the strained relations between the state and its frustrated poor, and between civil society and the immigrant class circumscribed to its périphérique—the name Bourouissa would later give to the series of photographs, after the circular highway separating Paris from its outer suburbs. The company announced on Monday that it has

The company announced on Monday that it has  Modern civilization, it is said, would be impossible without measurement. And measurement would be pointless if we weren’t all using the same units. So, for nearly 150 years, the world’s metrologists have agreed on strict definitions for units of measurement through the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, known by its French acronym, B.I.P.M., and based outside Paris. Nowadays the bureau regulates the seven base units that govern time, length, mass, electrical current, temperature, the intensity of light and the amount of a substance. Together, these units are the language of science, technology and commerce.

Modern civilization, it is said, would be impossible without measurement. And measurement would be pointless if we weren’t all using the same units. So, for nearly 150 years, the world’s metrologists have agreed on strict definitions for units of measurement through the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, known by its French acronym, B.I.P.M., and based outside Paris. Nowadays the bureau regulates the seven base units that govern time, length, mass, electrical current, temperature, the intensity of light and the amount of a substance. Together, these units are the language of science, technology and commerce. The Seattle Times chatted with Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk about her immersive, visionary 1,000-page novel that follows the extraordinary life of Jacob Frank, a Polish Jew who believed himself to be the Messiah and commanded a large religious movement in the 18th century.

The Seattle Times chatted with Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk about her immersive, visionary 1,000-page novel that follows the extraordinary life of Jacob Frank, a Polish Jew who believed himself to be the Messiah and commanded a large religious movement in the 18th century. On April 4,

On April 4, I think we’re laboring under a moment in which many believe that the sole function of art is to provide moral guidance.

I think we’re laboring under a moment in which many believe that the sole function of art is to provide moral guidance.