Robin D. G. Kelley in Boston Review:

Robin D. G. Kelley in Boston Review:

Nearly every activist I encounter these days identifies as an abolitionist. To be sure, movements to abolish prisons and police have been around for decades, popularizing the idea that caging and terrorizing people makes us unsafe. However, the Black Spring rebellions revealed that the obscene costs of state violence can and should be reallocated for things that do keep us safe: housing, universal healthcare, living wage jobs, universal basic income, green energy, and a system of restorative justice. As abolition recently became the new watchword, everyone scrambled to understand its historical roots. Reading groups popped up everywhere to discuss W. E. B. Du Bois’s classic, Black Reconstruction in America (1935), since he was the one to coin the phrase “abolition democracy,” which Angela Y. Davis revived for her indispensable book of the same title.

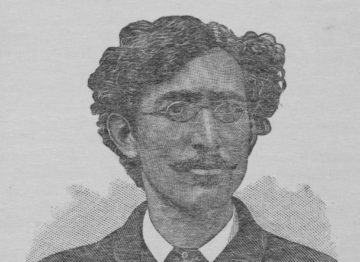

I happily participated in Black Reconstruction study groups and public forums meant to divine wisdom for our current movements. But I often wondered why no one was scrambling to resurrect T. Thomas Fortune’s Black and White: Land, Labor, and Politics in the South, published in 1884. After all, it was Fortune who wrote: “The South must spend less money on penitentiaries and more money on schools; she must use less powder and buckshot and more law and equity; she must pay less attention to politics and more attention to the development of her magnificent resources.”

More here.