Anthony Domestico at Commonweal:

We’ll start with a pair of shoes. In 1944, a young Italian woman named Emilia “Ilia” Terzulli marries an older English soldier named Esmond Warner. They’re an unlikely couple. Nicknamed “La Giraffa,” Ilia is tall, poor, gorgeous, and untraveled. Esmond is balding, bespectacled, and worldly. She’s not just Italian but southern Italian; he’s not just English but English English, his family’s wealth faded but not their lordly idiosyncrasies. (His mum goes by Mother Rat; his father, a former professional cricketer, by Plum; his childhood pet rat by Scoot.) And so, to make his Bari-born wife feel at home in South Kensington, Esmond buys Ilia a pair of shoes. More specifically, he buys her “bespoke brogues”: sturdy, plain-ish, yet expensive shoes that mark Ilia’s “formal enrolment in the world of the squirearchy, hunting, going to the point-to-point, the harriers, the beagles, the open-gardens scheme, the charity fête.”

We’ll start with a pair of shoes. In 1944, a young Italian woman named Emilia “Ilia” Terzulli marries an older English soldier named Esmond Warner. They’re an unlikely couple. Nicknamed “La Giraffa,” Ilia is tall, poor, gorgeous, and untraveled. Esmond is balding, bespectacled, and worldly. She’s not just Italian but southern Italian; he’s not just English but English English, his family’s wealth faded but not their lordly idiosyncrasies. (His mum goes by Mother Rat; his father, a former professional cricketer, by Plum; his childhood pet rat by Scoot.) And so, to make his Bari-born wife feel at home in South Kensington, Esmond buys Ilia a pair of shoes. More specifically, he buys her “bespoke brogues”: sturdy, plain-ish, yet expensive shoes that mark Ilia’s “formal enrolment in the world of the squirearchy, hunting, going to the point-to-point, the harriers, the beagles, the open-gardens scheme, the charity fête.”

We read about these brogues in Marina Warner’s Esmond and Ilia: An Unreliable Memoir (New York Review Books, 432 pp., $19.95).

more here.

One hundred and seventy-six years ago today, on the evening of Monday, June 22, 1846, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon—sixty years old and facing imminent financial ruin—locked himself in his studio in his house on Burwood Place, just off London’s Edgware Road. The month had been the hottest anyone could remember: that day, thermometers in the city stood at ninety degrees in the shade. Despite the heat, that morning Haydon had walked to a gunmaker’s on nearby Oxford Street and purchased a pistol. He spent the rest of the day at home, composing letters and writing a comprehensive, nineteen-clause will.

One hundred and seventy-six years ago today, on the evening of Monday, June 22, 1846, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon—sixty years old and facing imminent financial ruin—locked himself in his studio in his house on Burwood Place, just off London’s Edgware Road. The month had been the hottest anyone could remember: that day, thermometers in the city stood at ninety degrees in the shade. Despite the heat, that morning Haydon had walked to a gunmaker’s on nearby Oxford Street and purchased a pistol. He spent the rest of the day at home, composing letters and writing a comprehensive, nineteen-clause will. Stewart Brand is not a scientist. He’s not an artist, an engineer, or a programmer. Nor is he much of a writer or editor, though as the creator of the Whole Earth Catalog, that’s what he’s best known for. Brand, 83, is a huckster—one of the great hucksters in a time and place full of them. Over the course of his long life, Brand’s salesmanship has been so outstanding that scholars of the American 20th century have secured his place as a historical figure, picking out the blond son of Stanford from among his peers and seating him with inventors, activists, and politicians at the table of men to be remembered. But remembered for what, exactly?

Stewart Brand is not a scientist. He’s not an artist, an engineer, or a programmer. Nor is he much of a writer or editor, though as the creator of the Whole Earth Catalog, that’s what he’s best known for. Brand, 83, is a huckster—one of the great hucksters in a time and place full of them. Over the course of his long life, Brand’s salesmanship has been so outstanding that scholars of the American 20th century have secured his place as a historical figure, picking out the blond son of Stanford from among his peers and seating him with inventors, activists, and politicians at the table of men to be remembered. But remembered for what, exactly? All of us construct models of the world, and update them on the basis of evidence brought to us by our senses. Scientists try to be more rigorous about it, but we all do it. It’s natural that this process will depend on what form that sensory input takes. We know that animals, for example, are typically better or worse than humans at sight, hearing, and so on. And as Ed Yong points out in his new book, it goes far beyond that, as many animals use completely different sensory modalities, from echolocation to direct sensing of electric fields. We talk about what those different capabilities might mean for the animal’s-eye (and -ear, etc.) view of the world.

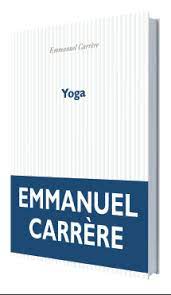

All of us construct models of the world, and update them on the basis of evidence brought to us by our senses. Scientists try to be more rigorous about it, but we all do it. It’s natural that this process will depend on what form that sensory input takes. We know that animals, for example, are typically better or worse than humans at sight, hearing, and so on. And as Ed Yong points out in his new book, it goes far beyond that, as many animals use completely different sensory modalities, from echolocation to direct sensing of electric fields. We talk about what those different capabilities might mean for the animal’s-eye (and -ear, etc.) view of the world. Near the end of his brilliant memoir

Near the end of his brilliant memoir  Lidia Yuknavitch’s extraordinary new novel is the weirdest, most mind-blowing book about America I’ve ever inhaled. Part history, part prophecy, all fever dream, “

Lidia Yuknavitch’s extraordinary new novel is the weirdest, most mind-blowing book about America I’ve ever inhaled. Part history, part prophecy, all fever dream, “ Can artificial intelligence come alive?

Can artificial intelligence come alive? Y

Y Microscopic mites that live in human pores and mate on our faces at night are becoming such simplified organisms, due to their unusual lifestyles, that they may soon become one with humans, new research has found.

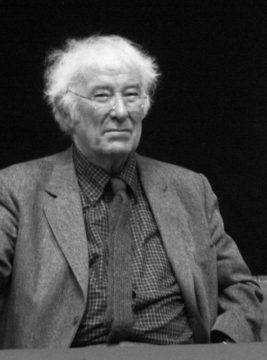

Microscopic mites that live in human pores and mate on our faces at night are becoming such simplified organisms, due to their unusual lifestyles, that they may soon become one with humans, new research has found. When he first began to publish poems, Seamus Heaney’s chosen pseudonym was ‘Incertus’, meaning ‘not sure of himself’. Characteristically, this was a subtle irony. While he referred in later years to a ‘residual Incertus’ inside himself, his early prominence was based on a sure-footed sense of his own direction, an energetic ambition, and his own formidable poetic strengths. It was also based on a respect for his readers which won their trust. ‘Poetry’s special status among the literary arts’, he suggested in a celebrated lecture, ‘derives from the audience’s readiness to . . . credit the poet with a power to open unexpected and unedited communications between our nature and the nature of the reality we inhabit’. Like T. S. Eliot, a constant if oblique presence in his writing life, he prized gaining access to ‘the auditory imagination’ and what it opened up: ‘a feeling for syllable and rhythm, penetrating far below the levels of conscious thought and feeling, invigorating every word’. His readers felt they shared in this.

When he first began to publish poems, Seamus Heaney’s chosen pseudonym was ‘Incertus’, meaning ‘not sure of himself’. Characteristically, this was a subtle irony. While he referred in later years to a ‘residual Incertus’ inside himself, his early prominence was based on a sure-footed sense of his own direction, an energetic ambition, and his own formidable poetic strengths. It was also based on a respect for his readers which won their trust. ‘Poetry’s special status among the literary arts’, he suggested in a celebrated lecture, ‘derives from the audience’s readiness to . . . credit the poet with a power to open unexpected and unedited communications between our nature and the nature of the reality we inhabit’. Like T. S. Eliot, a constant if oblique presence in his writing life, he prized gaining access to ‘the auditory imagination’ and what it opened up: ‘a feeling for syllable and rhythm, penetrating far below the levels of conscious thought and feeling, invigorating every word’. His readers felt they shared in this. Nature shows have always prized the dramatic: David Attenborough himself once told me, after filming a series on reptiles and amphibians, frogs “really don’t do very much until they breed, and snakes don’t do very much until they kill.” Such thinking has now become all-consuming, and nature’s dramas have become melodramas. The result is a subtle form of anthropomorphism, in which animals are of interest only if they satisfy familiar human tropes of violence, sex, companionship and perseverance. They’re worth viewing only when we’re secretly viewing a reflection of ourselves.

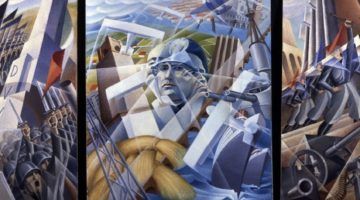

Nature shows have always prized the dramatic: David Attenborough himself once told me, after filming a series on reptiles and amphibians, frogs “really don’t do very much until they breed, and snakes don’t do very much until they kill.” Such thinking has now become all-consuming, and nature’s dramas have become melodramas. The result is a subtle form of anthropomorphism, in which animals are of interest only if they satisfy familiar human tropes of violence, sex, companionship and perseverance. They’re worth viewing only when we’re secretly viewing a reflection of ourselves. “Move fast and break things,” the digital dictum of today’s Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, could have been penned by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and his fellow Italian Futurists. Their famous

“Move fast and break things,” the digital dictum of today’s Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, could have been penned by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and his fellow Italian Futurists. Their famous  Earlier this year, “The Kashmir Files”—a blood-soaked historical drama with a nearly three-hour run time—became the top-grossing Hindi film since the start of the pandemic. The contested region of Kashmir has caused unending conflict between India and Pakistan. In Indian-administered Kashmir, the Army has brutally subjected Muslims to extensive human-rights violations, with tens of thousands killed, thousands of forced disappearances, and an extremely high incidence of rape—which has been used, according to Human Rights Watch, as a “counterinsurgency tactic” to “create a climate of fear.” But this film tells a different story.

Earlier this year, “The Kashmir Files”—a blood-soaked historical drama with a nearly three-hour run time—became the top-grossing Hindi film since the start of the pandemic. The contested region of Kashmir has caused unending conflict between India and Pakistan. In Indian-administered Kashmir, the Army has brutally subjected Muslims to extensive human-rights violations, with tens of thousands killed, thousands of forced disappearances, and an extremely high incidence of rape—which has been used, according to Human Rights Watch, as a “counterinsurgency tactic” to “create a climate of fear.” But this film tells a different story. When Jennifer Mason posted an ad for a postdoc position in early March, she was eager to have someone on board by April or May to tackle recently funded projects. Instead, it took 2 months to receive a single application. Since then, only two more have come in. “Money is just sitting there that isn’t being used … and there’s these projects that aren’t moving anywhere as a result,” says Mason, an assistant professor in genetics at Clemson University.

When Jennifer Mason posted an ad for a postdoc position in early March, she was eager to have someone on board by April or May to tackle recently funded projects. Instead, it took 2 months to receive a single application. Since then, only two more have come in. “Money is just sitting there that isn’t being used … and there’s these projects that aren’t moving anywhere as a result,” says Mason, an assistant professor in genetics at Clemson University.