Adrian Cho in Science:

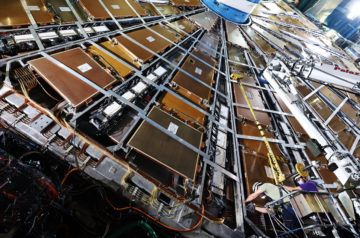

A decade ago, particle physicists thrilled the world. On 4 July 2012, 6000 researchers working with the world’s biggest atom smasher, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at the European particle physics laboratory, CERN, announced they had discovered the Higgs boson, a massive, fleeting particle key to their abstruse explanation of how other fundamental particles get their mass. The discovery fulfilled a 45-year-old prediction, completed a theory called the standard model, and thrust physicists into the spotlight.

Then came a long hangover. Before the 27-kilometer-long ring-shaped LHC started to take data in 2010, physicists fretted that it might produce the Higgs and nothing else, leaving no clue to what lies beyond the standard model. So far, that nightmare scenario is coming true. “It’s a bit disappointing,” allows Barry Barish, a physicist at the California Institute of Technology. “I thought we would discover supersymmetry,” the leading extension of the standard model.

More here.

In my nine years of doing this work I have seen an increasing demonisation of the clients of sex workers, even while I’ve seen increasing support for sex workers themselves. Much of the discussion around sex-worker rights focuses on the workers, how often marginalised people enter the industry out of financial necessity, and how criminalising that only further marginalises them, by forcing them into more dangerous scenarios and punishing them for their need. All this is of course of pre-eminent importance. And I think that the rights of sex workers shouldn’t rely on the value or respectability of the work itself—it is simply a human rights and labour rights issue. Sex workers should be able to speak about exploitation and abuse in the industry without that being used against us to argue for the eradication of the industry itself—in the same way migrant workers are speaking about working conditions on Australian farms without it leading to a cry to shut down agriculture.

In my nine years of doing this work I have seen an increasing demonisation of the clients of sex workers, even while I’ve seen increasing support for sex workers themselves. Much of the discussion around sex-worker rights focuses on the workers, how often marginalised people enter the industry out of financial necessity, and how criminalising that only further marginalises them, by forcing them into more dangerous scenarios and punishing them for their need. All this is of course of pre-eminent importance. And I think that the rights of sex workers shouldn’t rely on the value or respectability of the work itself—it is simply a human rights and labour rights issue. Sex workers should be able to speak about exploitation and abuse in the industry without that being used against us to argue for the eradication of the industry itself—in the same way migrant workers are speaking about working conditions on Australian farms without it leading to a cry to shut down agriculture. They span three continents, but a trio of researchers who’ve never met share a singular focus made vital by the still-raging pandemic: deciphering the causes of Long Covid and figuring out how to treat it.

They span three continents, but a trio of researchers who’ve never met share a singular focus made vital by the still-raging pandemic: deciphering the causes of Long Covid and figuring out how to treat it. On March 9, 1945, an armada of more than three hundred B-29s flew fifteen hundred miles across the Pacific to attack Tokyo from the air. The planes carried incendiary bombs to be dropped at low altitudes. Beginning shortly after midnight, sixteen hundred and sixty-five tons of bombs fell on the city.

On March 9, 1945, an armada of more than three hundred B-29s flew fifteen hundred miles across the Pacific to attack Tokyo from the air. The planes carried incendiary bombs to be dropped at low altitudes. Beginning shortly after midnight, sixteen hundred and sixty-five tons of bombs fell on the city. S

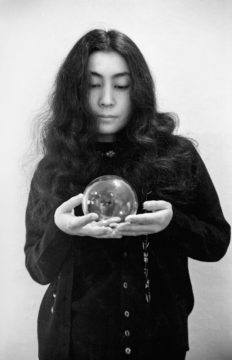

S PAINTED IN THE 1950S on the walls of her sons’ bedroom and later collected in a children’s book called The Milk of Dreams, Leonora Carrington’s wicked fairy tales inspired the title and tenor of the Fifty-Ninth Venice Biennale. Filled with disobedient children, deviant friendships, orphaned monsters, evil crones, sentient meat, hungry furniture, misplaced heads, scatological warfare, and pharmacological magic, Carrington’s stories struck curator Cecilia Alemani for their construction of what she describes as “a world free of hierarchies, where everyone can become something else.” Alemani endeavored to create something like this world in her beautiful and perturbing exhibition, and to a great degree she has succeeded.

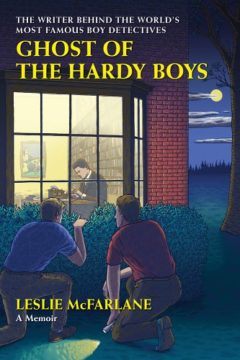

PAINTED IN THE 1950S on the walls of her sons’ bedroom and later collected in a children’s book called The Milk of Dreams, Leonora Carrington’s wicked fairy tales inspired the title and tenor of the Fifty-Ninth Venice Biennale. Filled with disobedient children, deviant friendships, orphaned monsters, evil crones, sentient meat, hungry furniture, misplaced heads, scatological warfare, and pharmacological magic, Carrington’s stories struck curator Cecilia Alemani for their construction of what she describes as “a world free of hierarchies, where everyone can become something else.” Alemani endeavored to create something like this world in her beautiful and perturbing exhibition, and to a great degree she has succeeded. This example of calmness in the face of disaster didn’t really help. It was all very well for Dave Fearless to meet catastrophe with aplomb. He could count on Bob Vilett and Captain Broadbeam to haul him to the surface, while Pat Stoodles lent encouragement by bellowing “Heave-ho, bejabers!” I couldn’t count on anyone—except, perhaps, Edward Stratemeyer.

This example of calmness in the face of disaster didn’t really help. It was all very well for Dave Fearless to meet catastrophe with aplomb. He could count on Bob Vilett and Captain Broadbeam to haul him to the surface, while Pat Stoodles lent encouragement by bellowing “Heave-ho, bejabers!” I couldn’t count on anyone—except, perhaps, Edward Stratemeyer. The COVID-19 pandemic was foreseen. Experts everywhere had long predicted a global viral outbreak and called for action to prevent it. World leaders, on the whole, did little. Now, with COVID-19 still raging, Bill Gates has produced a manifesto on what must be done to prevent the next pandemic. Written in accessible prose that even a busy world leader could not fail to grasp, the global-health philanthropist offers some life-saving ideas that are ambitious and achievable — if political leaders act.

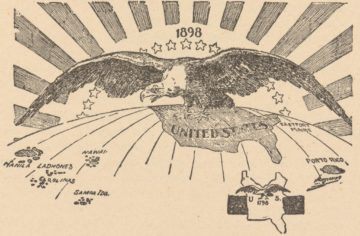

The COVID-19 pandemic was foreseen. Experts everywhere had long predicted a global viral outbreak and called for action to prevent it. World leaders, on the whole, did little. Now, with COVID-19 still raging, Bill Gates has produced a manifesto on what must be done to prevent the next pandemic. Written in accessible prose that even a busy world leader could not fail to grasp, the global-health philanthropist offers some life-saving ideas that are ambitious and achievable — if political leaders act. A student once asked—after a classroom discussion of how 19th-century westward expansion connected to the ongoing injustices of American military bases in the Pacific—what she was supposed to do with this knowledge. Her question was as genuine as it was perceptive. It also felt like I had, again, failed.

A student once asked—after a classroom discussion of how 19th-century westward expansion connected to the ongoing injustices of American military bases in the Pacific—what she was supposed to do with this knowledge. Her question was as genuine as it was perceptive. It also felt like I had, again, failed. But my interest, I clarified, while probably morbid, is not merely personal. It stems from a keenly felt, soul-sucking disillusionment. By accident of birth I am a modern, which means I will never know a charmed world. A world of consecrated hosts and faerie-haunted forests, where the line between individual agency and impersonal force is blurred at best. Gone is the idea of a porous human self, vulnerable to immaterial forces beyond his control. Significance has retreated from the outer world into our respective skulls, where, over time, it has stiffened, bloated, and finally decomposed into nothing, into dust.

But my interest, I clarified, while probably morbid, is not merely personal. It stems from a keenly felt, soul-sucking disillusionment. By accident of birth I am a modern, which means I will never know a charmed world. A world of consecrated hosts and faerie-haunted forests, where the line between individual agency and impersonal force is blurred at best. Gone is the idea of a porous human self, vulnerable to immaterial forces beyond his control. Significance has retreated from the outer world into our respective skulls, where, over time, it has stiffened, bloated, and finally decomposed into nothing, into dust. Who are we? Where do we come from? Who or what were the people, the land, the gods who made us? These questions have perplexed and haunted us ever since human beings evolved.

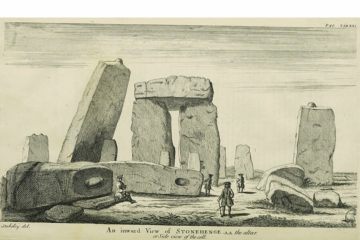

Who are we? Where do we come from? Who or what were the people, the land, the gods who made us? These questions have perplexed and haunted us ever since human beings evolved. On Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, rests an extraordinary monument that has puzzled and inspired people for millennia: the circular set of rocks known as Stonehenge. The iconic scene, so precisely designed and constructed, provokes a litany of questions: What motivated the Neolithic people to create such a thing? Where did the huge, 20-ton stones come from? How was it built?

On Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, rests an extraordinary monument that has puzzled and inspired people for millennia: the circular set of rocks known as Stonehenge. The iconic scene, so precisely designed and constructed, provokes a litany of questions: What motivated the Neolithic people to create such a thing? Where did the huge, 20-ton stones come from? How was it built? Juneteenth — a portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth” — became a federal holiday just last year, but Black Americans, particularly Black Texans, have been celebrating it for generations. The first Juneteenth festivities took place in the late 19th century in Texas’s Emancipation Park, and combined

Juneteenth — a portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth” — became a federal holiday just last year, but Black Americans, particularly Black Texans, have been celebrating it for generations. The first Juneteenth festivities took place in the late 19th century in Texas’s Emancipation Park, and combined  They are the ultimate “how to draw” books for a young child, created by a doting dad who just happened to be one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. The granddaughter of

They are the ultimate “how to draw” books for a young child, created by a doting dad who just happened to be one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. The granddaughter of