Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack newsletter, The Hinternet:

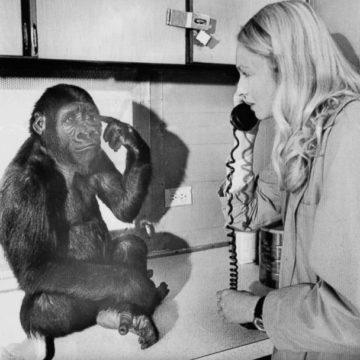

I would like at least to begin here an argument that supports the following points. First, we have no strong evidence of any currently existing artificial system’s capacity for conscious experience, even if in principle it is not impossible that an artificial system could become conscious. Second, such a claim as to the uniqueness of conscious experience in evolved biological systems is fully compatible with naturalism, as it is based on the idea that consciousness is a higher-order capacity resulting from the gradual unification of several prior capacities —embodied sensation, notably— that for most of their existence did not involve consciousness. Any AI project that seeks to skip over these capacities and to rush straight to intellectual self-awareness on the part of the machine is, it seems, going to miss some crucial steps. However, finally, there is at least some evidence at present that AI is on the path to consciousness, even without having been endowed with anything like a body or a sensory apparatus that might give it the sort of phenomenal experience we human beings know and value. This path is, namely, the one that sees the bulk of the task of becoming conscious, whether one is an animal or a machine, as lying in the capacity to model other minds.

I would like at least to begin here an argument that supports the following points. First, we have no strong evidence of any currently existing artificial system’s capacity for conscious experience, even if in principle it is not impossible that an artificial system could become conscious. Second, such a claim as to the uniqueness of conscious experience in evolved biological systems is fully compatible with naturalism, as it is based on the idea that consciousness is a higher-order capacity resulting from the gradual unification of several prior capacities —embodied sensation, notably— that for most of their existence did not involve consciousness. Any AI project that seeks to skip over these capacities and to rush straight to intellectual self-awareness on the part of the machine is, it seems, going to miss some crucial steps. However, finally, there is at least some evidence at present that AI is on the path to consciousness, even without having been endowed with anything like a body or a sensory apparatus that might give it the sort of phenomenal experience we human beings know and value. This path is, namely, the one that sees the bulk of the task of becoming conscious, whether one is an animal or a machine, as lying in the capacity to model other minds.

More here.

Nestled among the impressive domes and spires of Yale University is the simple office of

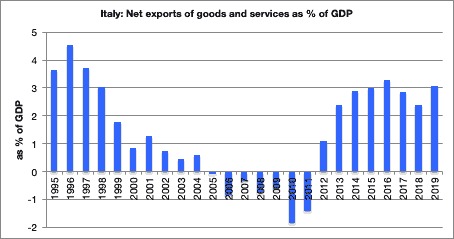

Nestled among the impressive domes and spires of Yale University is the simple office of  1. Italy is living below its means

1. Italy is living below its means Dear George Orwell,

Dear George Orwell, A plump larva the length of a paper clip can survive on the material that makes Styrofoam. The organism, commonly called a “superworm,” could transform the way waste managers dispose of one of the most common components in landfills, researchers said, potentially slowing a mounting garbage crisis that is exacerbating climate change. In a paper

A plump larva the length of a paper clip can survive on the material that makes Styrofoam. The organism, commonly called a “superworm,” could transform the way waste managers dispose of one of the most common components in landfills, researchers said, potentially slowing a mounting garbage crisis that is exacerbating climate change. In a paper  PROMINENT WHITE FEMINISTS

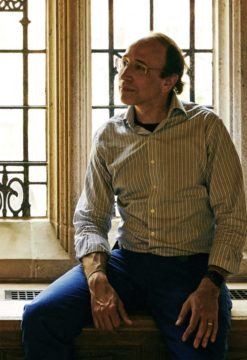

PROMINENT WHITE FEMINISTS Jim Al-Khalili has an enviable gig. The Iraqi-British scientist gets to ponder some of the deepest questions—What is time? How do nature’s forces work?—while living the life of a TV and radio personality. Al-Khalili hosts The Life Scientific, a show on BBC Radio 4 featuring his interviews with scientists on the impact of their research and what inspires and motivates them. He’s also presented documentaries and authored popular science books, including a novel, Sun Fall, about the crisis that unfolds when, in 2041, Earth’s magnetic field starts to fail. His latest book, The Joy of Science, is his response to a different crisis.

Jim Al-Khalili has an enviable gig. The Iraqi-British scientist gets to ponder some of the deepest questions—What is time? How do nature’s forces work?—while living the life of a TV and radio personality. Al-Khalili hosts The Life Scientific, a show on BBC Radio 4 featuring his interviews with scientists on the impact of their research and what inspires and motivates them. He’s also presented documentaries and authored popular science books, including a novel, Sun Fall, about the crisis that unfolds when, in 2041, Earth’s magnetic field starts to fail. His latest book, The Joy of Science, is his response to a different crisis. Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World:

Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World: Nóra Schultz in Tocqueville 21:

Nóra Schultz in Tocqueville 21: Kate Kirkpatrickis and Sonia Kruks in Aeon:

Kate Kirkpatrickis and Sonia Kruks in Aeon: I admit to having been skeptical, ahead of time, of the

I admit to having been skeptical, ahead of time, of the  When the Restoration ended his career in Britain’s Commonwealth government in 1660, John Milton turned his full attention to the verse tragedy he’d started around 1640, then called “Adam Unparadised.” By now in his 50s, blind and ailing, Milton composed “Paradise Lost” aloud, in bed or (per witnesses) “leaning backward obliquely in an easy chair, with his leg flung over the elbow of it,” memorizing the stanzas to be transcribed in another’s hand.

When the Restoration ended his career in Britain’s Commonwealth government in 1660, John Milton turned his full attention to the verse tragedy he’d started around 1640, then called “Adam Unparadised.” By now in his 50s, blind and ailing, Milton composed “Paradise Lost” aloud, in bed or (per witnesses) “leaning backward obliquely in an easy chair, with his leg flung over the elbow of it,” memorizing the stanzas to be transcribed in another’s hand. EARLY IN ELIF BATUMAN’S NEW NOVEL Either/Or, she quotes a blurb on the front of Kazuo Ishiguro’s An Artist of the Floating World, extracted from its 1986 review in the New York Times. “Good writers abound—good novelists are very rare,” the critic theorizes, deeming Ishiguro “not only a good writer, but also a wonderful novelist.” For Either/Or’s narrator, the distinction comes as a shock. Since she was young, Selin has aspired to become a novelist, and she views much of her life to date as training for that vocation. Assessing herself according to the reviewer’s implied rubric, Selin realizes that her facility with language, her sparkling insights and clever turns of phrase, may not be sufficient. “It was what I had been counting on,” she thinks. “My sense of being a good writer. My stomach sank with the knowledge of how wrong I had been.” This is in some sense the anxiety that haunts Either/Or: Batuman is demonstrably, incontrovertibly a good writer—but is she a good novelist? (And what is a good novel anyway?)

EARLY IN ELIF BATUMAN’S NEW NOVEL Either/Or, she quotes a blurb on the front of Kazuo Ishiguro’s An Artist of the Floating World, extracted from its 1986 review in the New York Times. “Good writers abound—good novelists are very rare,” the critic theorizes, deeming Ishiguro “not only a good writer, but also a wonderful novelist.” For Either/Or’s narrator, the distinction comes as a shock. Since she was young, Selin has aspired to become a novelist, and she views much of her life to date as training for that vocation. Assessing herself according to the reviewer’s implied rubric, Selin realizes that her facility with language, her sparkling insights and clever turns of phrase, may not be sufficient. “It was what I had been counting on,” she thinks. “My sense of being a good writer. My stomach sank with the knowledge of how wrong I had been.” This is in some sense the anxiety that haunts Either/Or: Batuman is demonstrably, incontrovertibly a good writer—but is she a good novelist? (And what is a good novel anyway?) No wonder, too, then, that there is a current public of soi-disant intellectuals eager to learn about past experiments in living, especially those with a significant philosophical dimension. And so we have Peter Neumann’s Jena 1800: The Republic of Free Spirits (translated by Shelley Frisch), “a fascinating and highly readable story of ideas, art, love, and war,” as one blurb has it, and a picture of “a world intoxicated with the possibilities of thought,” according to another. Jena in 1798 to 1800 was a backwater provincial city of 5,000 residents, one-fifth of whom were students. Initially attracted by the presences at the university first of Karl Leonhard Reinhold and then J. G. Fichte, both of whom were associated with the free thinking of Kantianism and the French Revolution, a circle of intellectual friends, including women as equals as well as men, formed around the brothers August and Friedrich Schlegel.

No wonder, too, then, that there is a current public of soi-disant intellectuals eager to learn about past experiments in living, especially those with a significant philosophical dimension. And so we have Peter Neumann’s Jena 1800: The Republic of Free Spirits (translated by Shelley Frisch), “a fascinating and highly readable story of ideas, art, love, and war,” as one blurb has it, and a picture of “a world intoxicated with the possibilities of thought,” according to another. Jena in 1798 to 1800 was a backwater provincial city of 5,000 residents, one-fifth of whom were students. Initially attracted by the presences at the university first of Karl Leonhard Reinhold and then J. G. Fichte, both of whom were associated with the free thinking of Kantianism and the French Revolution, a circle of intellectual friends, including women as equals as well as men, formed around the brothers August and Friedrich Schlegel. Although existentialist philosophers rarely labeled themselves as such or agreed on a definition of what they were doing, existentialism is a coherent and sound philosophy. It begins with the claim that “existence precedes essence,” meaning that people enter the world (they exist) before they can be said to have a fixed definition (or essence). They are free to create their own essence, and with this freedom comes responsibility. The contrast between how strange it is to exist and the reality that we are here is called “absurdity.” From absurdity, nihilists would avow that life is meaningless, and thus do whatever they want. Existentialists, however, typically reject nihilism and embrace authenticity. For Martin Heidegger, authenticity was related to our “being toward death.” For Friedrich Nietzsche, the “eternal return of the same” counsels us to live as if our life will repeat itself eternally.

Although existentialist philosophers rarely labeled themselves as such or agreed on a definition of what they were doing, existentialism is a coherent and sound philosophy. It begins with the claim that “existence precedes essence,” meaning that people enter the world (they exist) before they can be said to have a fixed definition (or essence). They are free to create their own essence, and with this freedom comes responsibility. The contrast between how strange it is to exist and the reality that we are here is called “absurdity.” From absurdity, nihilists would avow that life is meaningless, and thus do whatever they want. Existentialists, however, typically reject nihilism and embrace authenticity. For Martin Heidegger, authenticity was related to our “being toward death.” For Friedrich Nietzsche, the “eternal return of the same” counsels us to live as if our life will repeat itself eternally.