Category: Archives

Saturday, July 2, 2022

A Cold Drink of Objectivity

Leonard Benardo in Dissent:

Leonard Benardo in Dissent:

There was a cultural moment a few decades ago, capped by the absorbing 1998 documentary Arguing the World, when scholarship of and nostalgia for the so-called New York intellectuals was at its acme. A groaning shelf of titles spotlighted one or another aspect of this august midcentury group, which was analyzed, fawned over, and (far too hastily) lamented as the last great gasp of public intellectuals in America. The bold-faced names of the so-called Partisan Review “crowd”—Dwight Macdonald, Hannah Arendt, Mary McCarthy, Lionel Trilling, James Baldwin, Susan Sontag—had all been associated with a handful of small-circulation literary journals and were celebrities to a select few.

Amid the glorification, one name seemed to fall through the cracks, or at least not fit as snugly as the others into the lineup of those deemed worthy of sustained attention. Despite being a widely respected intellectual and writing prodigiously on arts and ideas for those same small publications, critic Harold Rosenberg received only a single, parenthetical mention in one of the central books of the period, David Laskin’s Partisans. Granted, Rosenberg was probably the hardest to pigeonhole among that complex group. He was in it but not necessarily of it, and he was intellectually nourished by his own independent and aggressively held political positions. Bolstered by a Marxism in which the structural challenges of commodification and capitalism were front and center, Rosenberg was nonetheless fiercely dedicated to the notion of autonomy and agency in culture.

More here.

My friend, the man who tried to kill Hitler

Raymond Geuss in The New Statesman:

Raymond Geuss in The New Statesman:

“Who is to blame? Someone must be to blame.” The impulse to ask this question in times of distress is almost overwhelming, and control over the way in which the answer to this question is sought, is power. The proponents of Brexit won the referendum the moment they were able to convince a significant swathe of people that the causes of their genuine grievances were not (as they in fact were) changes in world trade patterns and specific decisions made by parliament, but orders issuing from “Brussels”.

This example shows the close connection between assignment of blame and assessment of causality. But Christianity adds a third component to this complex: “guilt”. “You caused this; I blame you; you should feel guilty.” One might say that just as science governs (or ought to govern) assessments of cause and politics watches over assignments of blame, guilt is the domain of religion. But if religions are as plural as forms of politics, are the congealed forms that guilt assumes equally varied? Might there even be religious traditions lacking a concept of guilt altogether, or which assign a central place to some other psychic configuration?

From the age of 12, I attended a Catholic boarding school run by Hungarian priests who had emigrated to the US after the failed uprising in 1956. My experience there suggests that “guilt” too is more fragile and variable than one might assume.

More here.

Geographies in Transition

Jewellord T. Nem Singh in Phenomenal World:

Jewellord T. Nem Singh in Phenomenal World:

Though it failed to resolve a number of contentious issues, the COP26 meeting in Glasgow solidified a consensus around the need for a global transition to clean energy. Implicated in this transition is the wide-scale adoption of renewables: we must build larger wind turbines, produce more electric vehicles, and phase down coal factories in electrifying rapidly growing cities. Climate negotiations often refer to the “common but differentiated responsibility” that countries bear in promoting this transformation. But in reality, its protagonists are European governments and high-tech manufacturing companies involved in the production of renewable goods. And their policies have a cost—if the world meets the targets of the Paris Agreement, demand is likely to increase by 40 percent for copper and rare earth elements (REES), 60–70 percent for cobalt and nickel, and almost 90 percent for lithium over the next two decades.

The EU’s proposed Green Energy Deal secures critical minerals through open international markets, necessitating mineral extraction at a faster and more intense pace. But if it is to mitigate or overturn historical imbalances between North and South, the clean-energy transition cannot reproduce the same extractive relations underpinning industrial production. In what follows, I examine the green transition both as an opportunity and a challenge for resource-rich countries in the Global South. Importantly, I argue that we need to look beyond traditional growth-oriented industrial policies and the successful “catch up” of East Asian economies to develop inclusive and sustainable green development.

More here.

Brilliant Scholar or Predatory Charlatan?

Steven E. Aschheim at the LARB:

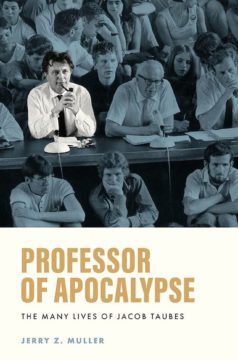

MANY READERS OF LARB and other literary journals may very well never even have heard the name — let alone be aware of the thought and personality — of the idiosyncratic philosopher and religious thinker Jacob Taubes (1923–1987). Why, then, would the distinguished intellectual historian Jerry Z. Muller dedicate many years to writing a highly detailed, nuanced biography of this apparently obscure figure? It would be sufficient to show that, in the second half of the 20th century, Taubes was an immensely well-connected and putatively brilliant man, an exotic, animating presence in the Western intellectual firmament, restlessly traversing Europe, the United States, and Israel. But what gives this study its special flavor is the fascinating, quasi-erotic, well-nigh demonic nature of the man’s personality and Muller’s tantalizing connection of these features to Taubes’s philosophical ruminations and religious and historical pursuits. Given his intensity and radicalism, his wildly vacillating moods and relationships, his unending contempt for cozy and settled bourgeois liberalism, and his search for some kind of messianic universal future, the title Muller has chosen for his biography, Professor of Apocalypse: The Many Lives of Jacob Taubes, could not be more apt.

MANY READERS OF LARB and other literary journals may very well never even have heard the name — let alone be aware of the thought and personality — of the idiosyncratic philosopher and religious thinker Jacob Taubes (1923–1987). Why, then, would the distinguished intellectual historian Jerry Z. Muller dedicate many years to writing a highly detailed, nuanced biography of this apparently obscure figure? It would be sufficient to show that, in the second half of the 20th century, Taubes was an immensely well-connected and putatively brilliant man, an exotic, animating presence in the Western intellectual firmament, restlessly traversing Europe, the United States, and Israel. But what gives this study its special flavor is the fascinating, quasi-erotic, well-nigh demonic nature of the man’s personality and Muller’s tantalizing connection of these features to Taubes’s philosophical ruminations and religious and historical pursuits. Given his intensity and radicalism, his wildly vacillating moods and relationships, his unending contempt for cozy and settled bourgeois liberalism, and his search for some kind of messianic universal future, the title Muller has chosen for his biography, Professor of Apocalypse: The Many Lives of Jacob Taubes, could not be more apt.

more here.

Jerry Z. Muller: What Jacob Taubes Saw in Carl Schmitt

‘In Search of Us’ by Lucy Moore

Fara Dabhoiwala at The Guardian:

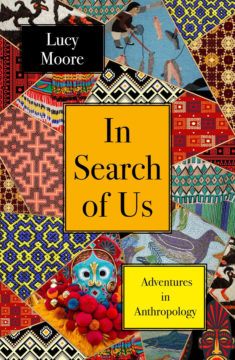

What linked these loosely connected scholars, the book suggests, was their interest in using the study of exotic cultures to illuminate the peculiarities of the “civilised” world. As Malinowski put it, “in grasping the essential outlook of others, with reverence and real understanding, due even to savages, we cannot help widening our own”. Anthropology thus became a means of showing what humans had in common, rather than what separated them.

What linked these loosely connected scholars, the book suggests, was their interest in using the study of exotic cultures to illuminate the peculiarities of the “civilised” world. As Malinowski put it, “in grasping the essential outlook of others, with reverence and real understanding, due even to savages, we cannot help widening our own”. Anthropology thus became a means of showing what humans had in common, rather than what separated them.

One admirer of William Rivers’s intellectual approach was especially impressed by “his lovely gift of coordinating apparently unrelated facts”. The same could be said of Moore. When Malinowski arrived on the Trobriand Islands, she tells us, he brought with him 24 crates of supplies, including “lemonade crystals, tinned oysters and lobster, various kinds of chocolate and cocoa, Spanish olives, cod roes, jugged hare, tinned and dried vegetables, half-hams, French brandy, tea, six different kinds of jam and plenty of condensed milk”.

more here.

Saturday Poem

The Correct Approach

The ancients spoke well:

briefly – but well.

Their thoughts had little wings –

like Hermes’s –

the ancients were not concerned

that someone might misunderstand –

everyone understood them.

But if one’s mind were weak,

he will quietly become intimate with

a Muse, one of the nine.

And the Muse,

inclining her head gracefully,

will teach him.

She will teach him to continue to stay

silent and silent and silent.

And if she permits him to speak

he will have to speak in hexameters.

by Regina Derieva

from Post Road Magazine, Issue 38

translation from Russian by Katie Farris and Ilya Kaminsky

Death by Video

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

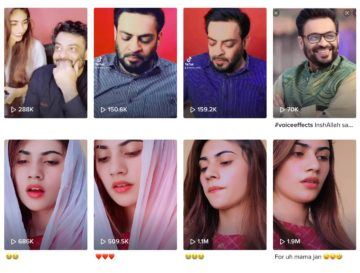

THE SUMMERS ARE ALWAYS HOT in Karachi, Pakistan’s most populous city. Temperatures hover above one hundred degrees and power outages are the norm. The wealthy use diesel or petrol to power large generators that keep their air conditioners running. Everyone else just suffers and tries to survive with little hope of respite until the monsoons arrive. June 9 was a day just like this. At the home of Aamir Liaquat Hussain, a member of parliament who was also a renowned televangelist, servants were figuring out what they should do. They had heard a cry of pain from his bedroom—but the door was locked, according to local media reports. They worried that something untoward may have occurred.

THE SUMMERS ARE ALWAYS HOT in Karachi, Pakistan’s most populous city. Temperatures hover above one hundred degrees and power outages are the norm. The wealthy use diesel or petrol to power large generators that keep their air conditioners running. Everyone else just suffers and tries to survive with little hope of respite until the monsoons arrive. June 9 was a day just like this. At the home of Aamir Liaquat Hussain, a member of parliament who was also a renowned televangelist, servants were figuring out what they should do. They had heard a cry of pain from his bedroom—but the door was locked, according to local media reports. They worried that something untoward may have occurred.

They were correct. When they broke down the door of the room, they found their boss lying unresponsive on his bed. They tried to revive him and called an ambulance. He was unresponsive and was taken to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead. At the deceased man’s home, police carried out a search. Meanwhile, the family refused an autopsy—though, even after his burial, that matter was still being contested in court.

More here.

Roe Is as Good as Dead. It Was Never Enough Anyway

Rachel Rebouche in Boston Review:

Though the 1973 decision in Roe established a constitutionally protected right to abortion, it never guaranteed abortion access. The Supreme Court held only that state criminal laws banning abortion were an infringement of the constitutional right to privacy. Patients, in consultation with their physicians, could elect to have an abortion for any reason during the first trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester states could regulate abortions in order to protect the pregnant person’s health or the dignity of potential life, but after the second trimester, a state was permitted to ban abortion unless terminating the pregnancy was necessary to preserve the patient’s life or health. This trimester system was abandoned in 1992, when the Court held that states could restrict abortion before viability—around twenty-four weeks of gestation—so long as the regulation did not place a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.” The Court’s decision to reject Roe’s trimester framework nevertheless claimed to preserve “the essential holding of Roe.”

Though the 1973 decision in Roe established a constitutionally protected right to abortion, it never guaranteed abortion access. The Supreme Court held only that state criminal laws banning abortion were an infringement of the constitutional right to privacy. Patients, in consultation with their physicians, could elect to have an abortion for any reason during the first trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester states could regulate abortions in order to protect the pregnant person’s health or the dignity of potential life, but after the second trimester, a state was permitted to ban abortion unless terminating the pregnancy was necessary to preserve the patient’s life or health. This trimester system was abandoned in 1992, when the Court held that states could restrict abortion before viability—around twenty-four weeks of gestation—so long as the regulation did not place a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.” The Court’s decision to reject Roe’s trimester framework nevertheless claimed to preserve “the essential holding of Roe.”

More here.

Friday, July 1, 2022

Your Fitbit has stolen your soul

Justin E. H. Smith in UnHerd:

Philosophers have seldom lived up to the ideal of radical doubt that they often claim as the prime directive of their tradition. They insist on questioning everything, while nonetheless holding onto many pieties. Foremost among these, perhaps, is the commandment handed down from the Oracle at Delphi and characterised by Plato as a life-motto of his master Socrates: “Know thyself.”

Philosophers have seldom lived up to the ideal of radical doubt that they often claim as the prime directive of their tradition. They insist on questioning everything, while nonetheless holding onto many pieties. Foremost among these, perhaps, is the commandment handed down from the Oracle at Delphi and characterised by Plato as a life-motto of his master Socrates: “Know thyself.”

While this may seem an unassailable injunction, it is at least somewhat at odds with an equally ancient demand of Western philosophy, which may in fact be offered up in direct response to what the oracle says: “Don’t tell me what to do.” This response gets close to the spirit of the Cynics, who, like Plato, also believed they were following the teachings of Socrates, yet took his philosophy not to require some arduous process of self-examination, but only a simple and immediate decision to conduct one’s life according only to the law dictated by nature.

There are good reasons to defy the oracle beyond simply a distaste for taking orders. For one thing, it is not a settled matter that the commandment to “know thyself” can be followed at all, since it is not clear that there is anything to know. In the end the self may be the greatest “nothingburger” of all; there may simply be nothing there.

More here.

CRISPR, 10 Years On: Learning to Rewrite the Code of Life

Carl Zimmer in the New York Times:

Ten years ago this week, Jennifer Doudna and her colleagues published the results of a test-tube experiment on bacterial genes. When the study came out in the journal Science on June 28, 2012, it did not make headline news. In fact, over the next few weeks, it did not make any news at all.

Ten years ago this week, Jennifer Doudna and her colleagues published the results of a test-tube experiment on bacterial genes. When the study came out in the journal Science on June 28, 2012, it did not make headline news. In fact, over the next few weeks, it did not make any news at all.

Looking back, Dr. Doudna wondered if the oversight had something to do with the wonky title she and her colleagues had chosen for the study: “A Programmable Dual RNA-Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity.”

“I suppose if I were writing the paper today, I would have chosen a different title,” Dr. Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley, said in an interview.

Far from an esoteric finding, the discovery pointed to a new method for editing DNA, one that might even make it possible to change human genes.

“I remember thinking very clearly, when we publish this paper, it’s like firing the starting gun at a race,” she said.

More here.

Who speaks for Muslims?

Kenan Malik in Pandaemonium:

“Birmingham will not tolerate the disrespect of our Prophet… You will have repercussions for your actions.” So claimed a leader of a Muslim protest against the film The Lady of Heaven. There were similar protests in cities from Bradford to London. Fear of “repercussions” led the cinema chain Cineworld to withdraw the film from all its outlets; another chain, Showcase, soon followed.

“Birmingham will not tolerate the disrespect of our Prophet… You will have repercussions for your actions.” So claimed a leader of a Muslim protest against the film The Lady of Heaven. There were similar protests in cities from Bradford to London. Fear of “repercussions” led the cinema chain Cineworld to withdraw the film from all its outlets; another chain, Showcase, soon followed.

But who determines that a film is “disrespectful”, and to whom? Who speaks for Muslims? The Muslims who made the film? Or those who feel offended by it?

Whenever there is a protest about a film or a book or a play deemed racist or disrespectful to a particular community, many, particularly on the left, take those claims at face value, especially if that community happens to be Muslim. They take at face value, too, that the protesters are in some sense speaking for “the community” or the faith. Yet what is often called “offence to a community” is often a debate within those communities. And nowhere is this clearer than in the row over The Lady of Heaven.

More here.

Jon Stewart Acceptance Speech at 2022 Mark Twain Prize, Plus Others on Jon

Also watch tributes by Samantha Bee, Stephen Colbert, Steve Carell, Bassem Youssaf, Olivia Munn, Jimmy Kimmel and Ed Helms.

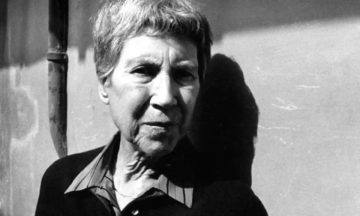

‘This is a perfect novel’: Sally Rooney on the book that transformed her life

Sally Rooney in The Guardian:

When I first read Natalia Ginzburg’s work several years ago, I felt as if I was reading something that had been written for me, something that had been written almost inside my own head or heart. I was astonished that I had never encountered Ginzburg’s work before: that no one, knowing me, had ever told me about her books. It was as if her writing was a very important secret that I had been waiting all my life to discover. Far more than anything I myself had ever written or even tried to write, her words seemed to express something completely true about my experience of living, and about life itself. This kind of transformative encounter with a book is, for me, very rare, a moment of contact with what seems to be the essence of human existence. For this reason, I wanted to write a little about Natalia Ginzburg and her novel All Our Yesterdays. I would like to address myself in particular to other readers who are right now awaiting, whether they know it or not, their first and special meeting with her work.

When I first read Natalia Ginzburg’s work several years ago, I felt as if I was reading something that had been written for me, something that had been written almost inside my own head or heart. I was astonished that I had never encountered Ginzburg’s work before: that no one, knowing me, had ever told me about her books. It was as if her writing was a very important secret that I had been waiting all my life to discover. Far more than anything I myself had ever written or even tried to write, her words seemed to express something completely true about my experience of living, and about life itself. This kind of transformative encounter with a book is, for me, very rare, a moment of contact with what seems to be the essence of human existence. For this reason, I wanted to write a little about Natalia Ginzburg and her novel All Our Yesterdays. I would like to address myself in particular to other readers who are right now awaiting, whether they know it or not, their first and special meeting with her work.

More here.

How some viruses make people smell extra-tasty to mosquitoes

Freda Kreier in Nature:

The viruses that cause the tropical diseases Zika and dengue fever can hijack the body odour of their hosts to their advantage, a study shows1. Both viruses alter how mice smell to make the animals more appetizing to hungry mosquitoes. This tactic could help the viruses to catch a ride to fresh targets, says co-author Gong Cheng, a microbiologist at Tsinghua University in Beijing. Techniques for interrupting this smelly takeover could help to control not only Zika and dengue, but also other mosquito-borne diseases, he says. The research was published on 30 June in Cell.

The viruses that cause the tropical diseases Zika and dengue fever can hijack the body odour of their hosts to their advantage, a study shows1. Both viruses alter how mice smell to make the animals more appetizing to hungry mosquitoes. This tactic could help the viruses to catch a ride to fresh targets, says co-author Gong Cheng, a microbiologist at Tsinghua University in Beijing. Techniques for interrupting this smelly takeover could help to control not only Zika and dengue, but also other mosquito-borne diseases, he says. The research was published on 30 June in Cell.

Researchers have known for decades that some diseases can change how their hosts smell, says James Logan, a disease-control specialist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Certain viruses and microorganisms have evolved to use this to their advantage. For instance, plants that are infected with the Cucumber mosaic virus release a molecule that attracts aphids, which the virus uses as a vector to infect new plants2. Scientists have also found that parasites that cause malaria advertise their hosts to passing mosquitoes through changes in body odour3.

To see whether the Zika and dengue viruses had also evolved ways to attract mosquitoes’ attention, Cheng and his colleagues infected mice with one or the other. They then placed infected and healthy mice in separate enclosures and wafted their scent into a mosquito-filled chamber that was connected to both enclosures, to see which group the insects preferred. Around 65–70% of the mosquitoes moved towards the enclosure with infected mice, suggesting that these animals smelled more appealing.

More here.

Friday Poem

Forbidden

Let me go back to my father

in the body of my mother the day he told her

having black children won’t save you when the revolution comes.

Let me do more than laugh,

like she did.

Let me go back to my mother and do more

than roll my eyes when she tells me,

I think deep down, in a past life, I was a black blues singer.

My mother remembers the convent

where she worked after I was born;

the nuns who played with me while she cleaned.

My father remembers the bedroom window

of their first apartment; his tired body

climbing through. It was best,

they agreed, if she signed the lease alone.

Scholars conclude:

the myths of violence that surround the black male

body protect the white female body

from harm. I conclude:

race was not not a factor in my parents’ attraction.

I am the product of their curiosity, their vengeance, their need.

They rescued each other from stories scripted

onto their bodies. They tasted forbidden and devoured each other

whole.

Let me build a house

where their memories diverge.

by Jamaica Baldwin

from the Smith College Poetry Center, 2008

Thursday, June 30, 2022

Zadie Smith Finds Her Way to Class

Todd Cronan in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Compassion might describe Smith’s basic approach as a writer. What motivated her to write? “Above all,” she says in a 2019 essay in The New York Review of Books, “I wanted to know what it was like to be everybody.” Her novels are tours de force of literary empathy, and White Teeth (2000), her breakout work, epitomizes a vision of multicultural possibility that the “less naïve” Smith could no longer accommodate. That world, the one she inhabited growing up, mixed “the relatively rich and the poor, the children of Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Sikhs, Protestants, Catholics, atheists, Marxists” as well as those who are “religious about Pilates.” Smith celebrates a world where these people “are all educated together in the same rooms, play together in the same playground, speak about their faiths — or lack of them — to each other.”

Compassion might describe Smith’s basic approach as a writer. What motivated her to write? “Above all,” she says in a 2019 essay in The New York Review of Books, “I wanted to know what it was like to be everybody.” Her novels are tours de force of literary empathy, and White Teeth (2000), her breakout work, epitomizes a vision of multicultural possibility that the “less naïve” Smith could no longer accommodate. That world, the one she inhabited growing up, mixed “the relatively rich and the poor, the children of Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Sikhs, Protestants, Catholics, atheists, Marxists” as well as those who are “religious about Pilates.” Smith celebrates a world where these people “are all educated together in the same rooms, play together in the same playground, speak about their faiths — or lack of them — to each other.”

At once we can begin to see the limitations of compassion, at least as a political idea. Smith’s empathetic universe is a world without ideology. Being rich and being poor, after all, are not subject positions worthy of affirmation; it would be perverse to celebrate a world flush with poverty. And yet Smith’s earlier novels revel in their capacity to turn ideological difference — Christian and Muslim, Marxist and atheist — into cultural difference, a choice between health food, exercise, and church on Sunday. No one wants to (or should want to) rid the world of cultures. Those differences should be celebrated. But the point of leftist politics, its difference from pluralism, is something else: to rid the world of poverty, which requires ridding it of the rich, first.

More here.

The rise of inequality research: can spanning disciplines help tackle injustice?

Virginia Gewin in Nature:

Generally, the unequal or unjust distribution of resources and opportunities in a society is studied in just one dimension, such as through income or education, says Maralani. Yet inequalities in income, wealth, education, health and access to technology are inter-related and differ by gender, race , ethnicity and geographical location in important ways. The root causes are multidimensional and dynamic. Some of the most influential work of the past decade — notably French economist Thomas Piketty’s 2013 book Capital in the Twenty-First Century — demonstrated how persistent inequality has become, even raising international concern.

Generally, the unequal or unjust distribution of resources and opportunities in a society is studied in just one dimension, such as through income or education, says Maralani. Yet inequalities in income, wealth, education, health and access to technology are inter-related and differ by gender, race , ethnicity and geographical location in important ways. The root causes are multidimensional and dynamic. Some of the most influential work of the past decade — notably French economist Thomas Piketty’s 2013 book Capital in the Twenty-First Century — demonstrated how persistent inequality has become, even raising international concern.

There’s an urgency driving increased interest in inequality research. “The reason for it is horrific — inequality is growing,” says Melanie Smallman at University College London, who studies how technology contributes to inequality.

More here.

Zoomorphising humanity

Usha Alexander at the RSPCA:

When thinkers and naturalists do talk about complex animal behaviours, their approach is usually constrained by the principle that when we imagine we see human-like motives, impulses and feelings in other animals, we must assume we’re only projecting our humanity onto them, the way we see human faces in the clouds.

When thinkers and naturalists do talk about complex animal behaviours, their approach is usually constrained by the principle that when we imagine we see human-like motives, impulses and feelings in other animals, we must assume we’re only projecting our humanity onto them, the way we see human faces in the clouds.

But what if it’s not that? What if, in fact, it’s the opposite: not me imbuing a non-human animal with human emotionality but, rather, me recognising the common feelings and sentience of non-human animals within myself? After all, science also tells us that we evolved from the same source as all other animals, that we share a great deal in common with our fellow species, from our DNA and physiology to our enmeshment in a web of deep ecological interdependence. Though widely accepted, this knowledge of our relatedness remains, for many of us, merely a scrap of abstract and esoteric information, detached from our more foundational philosophical certainty of human exceptionalism, supremacy and paramountcy.

More here. And an essay by Frans de Waal on the same theme here.