Leonard Benardo in Dissent:

Leonard Benardo in Dissent:

There was a cultural moment a few decades ago, capped by the absorbing 1998 documentary Arguing the World, when scholarship of and nostalgia for the so-called New York intellectuals was at its acme. A groaning shelf of titles spotlighted one or another aspect of this august midcentury group, which was analyzed, fawned over, and (far too hastily) lamented as the last great gasp of public intellectuals in America. The bold-faced names of the so-called Partisan Review “crowd”—Dwight Macdonald, Hannah Arendt, Mary McCarthy, Lionel Trilling, James Baldwin, Susan Sontag—had all been associated with a handful of small-circulation literary journals and were celebrities to a select few.

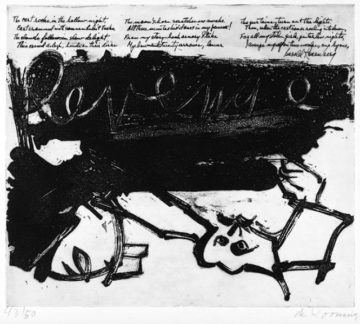

Amid the glorification, one name seemed to fall through the cracks, or at least not fit as snugly as the others into the lineup of those deemed worthy of sustained attention. Despite being a widely respected intellectual and writing prodigiously on arts and ideas for those same small publications, critic Harold Rosenberg received only a single, parenthetical mention in one of the central books of the period, David Laskin’s Partisans. Granted, Rosenberg was probably the hardest to pigeonhole among that complex group. He was in it but not necessarily of it, and he was intellectually nourished by his own independent and aggressively held political positions. Bolstered by a Marxism in which the structural challenges of commodification and capitalism were front and center, Rosenberg was nonetheless fiercely dedicated to the notion of autonomy and agency in culture.

More here.