George Blaustein in the European Review of Books:

Before pondering the locations of action cinema (and thus the vectors of our own nostalgias and aspirations), let us briefly rehearse the mystique of Tom Cruise’s action-hero Method-acting, and its storied relationship to cinema as art and industry.

Before pondering the locations of action cinema (and thus the vectors of our own nostalgias and aspirations), let us briefly rehearse the mystique of Tom Cruise’s action-hero Method-acting, and its storied relationship to cinema as art and industry.

The plot of Dead Reckoning (Part One) revolves around a fancy cruciform key that looks both antique and futuristic. It has two parts; when they’re locked fancily together, four jewel-like lights on the key’s bow glow, giving the key a Benjaminian aura of Unreproduzierbarkeit. Our protagonists have one part of the key; they need the other part. The key, we’re told, unlocks the as-yet-unrevealed device that will allow humanity to control or destroy an ominous artificial intelligence.

The AI — self-aware, rogue, malevolent — is Dead Reckoning (Part One)’s disembodied, inscrutably brilliant villain.

More here.

Palantir’s founding team, led by investor Peter Thiel and Alex Karp, wanted to create a company capable of using new data integration and data analytics technology — some of it developed to fight online payments fraud — to solve problems of law enforcement, national security, military tactics, and warfare. They called it Palantir, after the magical stones in The Lord of the Rings. Palantir, founded in 2003, developed its tools fighting terrorism after September 11, and has done extensive work for government agencies and corporations though much of its work is secret. It went

Palantir’s founding team, led by investor Peter Thiel and Alex Karp, wanted to create a company capable of using new data integration and data analytics technology — some of it developed to fight online payments fraud — to solve problems of law enforcement, national security, military tactics, and warfare. They called it Palantir, after the magical stones in The Lord of the Rings. Palantir, founded in 2003, developed its tools fighting terrorism after September 11, and has done extensive work for government agencies and corporations though much of its work is secret. It went  There is an old temple at Chavín de Huántar. The archaeological site lies halfway between Peru’s tropical lowlands and the coast, near the confluence of the Mosna and Huanchesca Rivers, tucked between jagged mountain cordilleras. Inside the temple, a U-shaped flat-topped pyramid, intricate carvings of animals exotic to the highlands cover the stone passageways that form a labyrinth between chambers. Jaguars. Harpy eagles. Caimans. Anacondas. Devotees once came here to consult oracles and perform bloodletting rituals. In the middle of the central cruciform room, illuminated by a beam of sunlight, stands a fifteen-foot-tall, triangular granite monolith that connects the floor to the ceiling. A figure has been etched into the rock. Googly eyes sit above a broad snout with round nostrils. Curly hair ending in snake heads, like Medusa, frames a snarling face. One hand is raised in the air, palm forward, as if permitting passage to another world. The other lays down at its side. Five curving claws protrude from its feet, where worshippers once laid lavish gifts of food and ceramics. This is El Lanzón.

There is an old temple at Chavín de Huántar. The archaeological site lies halfway between Peru’s tropical lowlands and the coast, near the confluence of the Mosna and Huanchesca Rivers, tucked between jagged mountain cordilleras. Inside the temple, a U-shaped flat-topped pyramid, intricate carvings of animals exotic to the highlands cover the stone passageways that form a labyrinth between chambers. Jaguars. Harpy eagles. Caimans. Anacondas. Devotees once came here to consult oracles and perform bloodletting rituals. In the middle of the central cruciform room, illuminated by a beam of sunlight, stands a fifteen-foot-tall, triangular granite monolith that connects the floor to the ceiling. A figure has been etched into the rock. Googly eyes sit above a broad snout with round nostrils. Curly hair ending in snake heads, like Medusa, frames a snarling face. One hand is raised in the air, palm forward, as if permitting passage to another world. The other lays down at its side. Five curving claws protrude from its feet, where worshippers once laid lavish gifts of food and ceramics. This is El Lanzón.

One can’t help but feel a sense of wonder reading about the bar-tailed godwit, a bird the size of a football, whose winter migration can take it from Alaska to New Zealand in one marathon flight across the Pacific Ocean. The ornithologists who’ve helped us understand the phenomenon of migration inspire wonder as well. Their ingenuity and zeal are at the heart of Rebecca Heisman’s delightful debut, “Flight Paths: How a Passionate and Quirky Group of Pioneering Scientists Solved the Mystery of Bird Migration.”

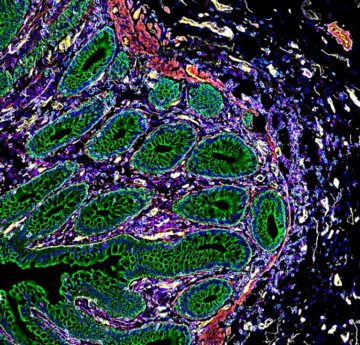

One can’t help but feel a sense of wonder reading about the bar-tailed godwit, a bird the size of a football, whose winter migration can take it from Alaska to New Zealand in one marathon flight across the Pacific Ocean. The ornithologists who’ve helped us understand the phenomenon of migration inspire wonder as well. Their ingenuity and zeal are at the heart of Rebecca Heisman’s delightful debut, “Flight Paths: How a Passionate and Quirky Group of Pioneering Scientists Solved the Mystery of Bird Migration.” Detailed maps of the cells in human organs show how the placenta commandeers the maternal blood supply, how kidney cells transition from healthy to diseased states and how cells in the intestine organize themselves into distinct neighbourhoods. These atlases, published on 19 July in Nature

Detailed maps of the cells in human organs show how the placenta commandeers the maternal blood supply, how kidney cells transition from healthy to diseased states and how cells in the intestine organize themselves into distinct neighbourhoods. These atlases, published on 19 July in Nature For the first time, the majority of information we consume as a species is controlled by algorithms built to capture our emotional attention. As a result, we hear more angry voices shouting fearful opinions and we see more threats and frightening news simply because these are the stories most likely to engage us. This engagement is profitable for everyone involved: producers, journalists, creators, politicians, and, of course, the platforms themselves.

For the first time, the majority of information we consume as a species is controlled by algorithms built to capture our emotional attention. As a result, we hear more angry voices shouting fearful opinions and we see more threats and frightening news simply because these are the stories most likely to engage us. This engagement is profitable for everyone involved: producers, journalists, creators, politicians, and, of course, the platforms themselves. The Earth’s atmosphere is good for some things, like providing something to breathe. But it does get in the way of astronomers, who have been successful at launching orbiting telescopes into space. But gravity and the ground are also useful for certain things, like walking around. The Moon, fortunately, provides gravity and a solid surface without any complications of a thick atmosphere — perfect for astronomical instruments. Building telescopes and other kinds of scientific instruments on the Moon is an expensive and risky endeavor, but the time may have finally arrived. I talk with astrophysicist Joseph Silk about the case for doing astronomy from the Moon, and what special challenges and opportunities are involved.

The Earth’s atmosphere is good for some things, like providing something to breathe. But it does get in the way of astronomers, who have been successful at launching orbiting telescopes into space. But gravity and the ground are also useful for certain things, like walking around. The Moon, fortunately, provides gravity and a solid surface without any complications of a thick atmosphere — perfect for astronomical instruments. Building telescopes and other kinds of scientific instruments on the Moon is an expensive and risky endeavor, but the time may have finally arrived. I talk with astrophysicist Joseph Silk about the case for doing astronomy from the Moon, and what special challenges and opportunities are involved. Imagine the entire cohort of U.S. graduating high school students this year as a group of one thousand bright-eyed 18-year-olds: kids of every class and race, spanning the whole spectrum of talent, wealth and oppression. What should the goal of progressive politics be for them? Where should attention be focused?

Imagine the entire cohort of U.S. graduating high school students this year as a group of one thousand bright-eyed 18-year-olds: kids of every class and race, spanning the whole spectrum of talent, wealth and oppression. What should the goal of progressive politics be for them? Where should attention be focused? O

O Things get especially interesting every weekend night about two and a half hours into the show, when Swift diverges from her otherwise precisely orchestrated set to perform two “surprise songs” from her catalog acoustically, never to be repeated at a later show, or so she says. The number of viewers in the live streams increase threefold, and fans on TikTok broadcast their feral reactions to Swift’s choices, which become ripe for close reading. “If I hear ‘friends break up’ I’m gonna kill myself,” one user watching the Cincinnati show

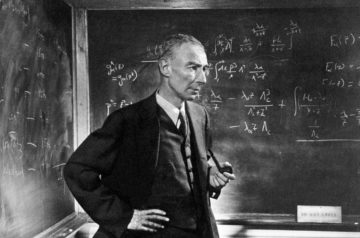

Things get especially interesting every weekend night about two and a half hours into the show, when Swift diverges from her otherwise precisely orchestrated set to perform two “surprise songs” from her catalog acoustically, never to be repeated at a later show, or so she says. The number of viewers in the live streams increase threefold, and fans on TikTok broadcast their feral reactions to Swift’s choices, which become ripe for close reading. “If I hear ‘friends break up’ I’m gonna kill myself,” one user watching the Cincinnati show  This week, the much anticipated movie Oppenheimer hits theaters, giving famed filmmaker Christopher Nolan’s take on the theoretical physicist who during World War II led the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic bomb. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who died in 1967, is known as a charismatic leader, eloquent public intellectual, and Red Scare victim who in 1954 lost his security clearance in part because of his earlier associations with suspected Communists. To learn about Oppenheimer the scientist, Science spoke with David C. Cassidy, a physicist and historian emeritus at Hofstra University. Cassidy has authored or edited 10 books, including J. Robert Oppenheimer and the American Century.

This week, the much anticipated movie Oppenheimer hits theaters, giving famed filmmaker Christopher Nolan’s take on the theoretical physicist who during World War II led the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic bomb. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who died in 1967, is known as a charismatic leader, eloquent public intellectual, and Red Scare victim who in 1954 lost his security clearance in part because of his earlier associations with suspected Communists. To learn about Oppenheimer the scientist, Science spoke with David C. Cassidy, a physicist and historian emeritus at Hofstra University. Cassidy has authored or edited 10 books, including J. Robert Oppenheimer and the American Century. Climate anxiety is understood by psychologists to be a form of ‘practical’ anxiety as it is considered a rational response to the threat of climate change and can lead to constructive behaviours. At a Melbourne Writers Festival panel in 2022, Else Fitzgerald described her debut short story collection, Everything Feels Like the End of the World, as an attempt to work through her own climate grief, a sorrow that has its roots in the successive periods of drought and flooding she experienced growing up in East Gippsland. This, surely – writing a book – is the kind of ‘constructive behaviour’ the psychologists have in mind. But what of climate anxiety that clamps down, that debilitates and immobilises? The anxiety I feel in relation to the climate crisis leaves me swinging wildly between maniacal bouts of information gathering and long periods of psychic paralysis, during which I work equally hard to avoid any mention of climate change and its attendant calamities.

Climate anxiety is understood by psychologists to be a form of ‘practical’ anxiety as it is considered a rational response to the threat of climate change and can lead to constructive behaviours. At a Melbourne Writers Festival panel in 2022, Else Fitzgerald described her debut short story collection, Everything Feels Like the End of the World, as an attempt to work through her own climate grief, a sorrow that has its roots in the successive periods of drought and flooding she experienced growing up in East Gippsland. This, surely – writing a book – is the kind of ‘constructive behaviour’ the psychologists have in mind. But what of climate anxiety that clamps down, that debilitates and immobilises? The anxiety I feel in relation to the climate crisis leaves me swinging wildly between maniacal bouts of information gathering and long periods of psychic paralysis, during which I work equally hard to avoid any mention of climate change and its attendant calamities.