Heidi Ledford in Nature:

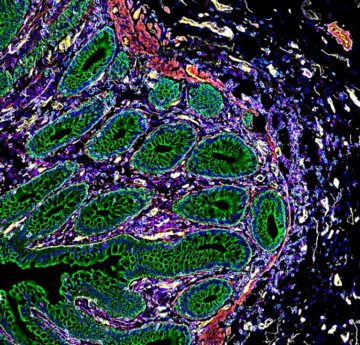

Detailed maps of the cells in human organs show how the placenta commandeers the maternal blood supply, how kidney cells transition from healthy to diseased states and how cells in the intestine organize themselves into distinct neighbourhoods. These atlases, published on 19 July in Nature1–3, are examples of a powerful and increasingly popular approach to studying the organs of the body in both health and disease. Each comprises hundreds of thousands of data points about gene activity and protein production in individual cells, which are then mapped to their specific location in the organ.

Detailed maps of the cells in human organs show how the placenta commandeers the maternal blood supply, how kidney cells transition from healthy to diseased states and how cells in the intestine organize themselves into distinct neighbourhoods. These atlases, published on 19 July in Nature1–3, are examples of a powerful and increasingly popular approach to studying the organs of the body in both health and disease. Each comprises hundreds of thousands of data points about gene activity and protein production in individual cells, which are then mapped to their specific location in the organ.

The hope is that the atlases will eventually yield clues about how to diagnose and treat disorders that can arise when those cells become injured or dysfunctional. “These cells organize themselves into neighbourhoods, towns, countries,” says Michael Snyder, a geneticist at Stanford University in California and an author of the study looking at the intestine3. “And it affects their function.”

Cell atlases

Technologies that allow researchers to monitor gene activity in individual cells have helped to spur the production of many cell atlases in recent years, including maps of blood vessels in the brain4 and of various types of tumour5–7. With time, these technologies have become more sophisticated, allowing researchers to incorporate information about a cell’s location and interrogate gene activity more thoroughly. The latest papers take this further by evaluating the abundance of dozens of proteins in each cell. The research is part of a consortium called the Human Biomolecular Atlas Program (HuBMAP), which is funded by the US National Institutes of Health and aims to develop tools to map out the cells of the human body.

More here.