Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio. White Dove Let US Fly, 2024.

Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio. White Dove Let US Fly, 2024.

Photo by Sughra Raza.

At the Whitney Biennial.

by Jeroen Bouterse

“You are aware”, I ask a pair of students celebrating their fourth successful die roll in a row, “that you are ruining this experiment?” They laugh obligingly. In four pairs, a small group of students is spending a few minutes rolling dice, awarding themselves 12 euros for every 5 or 6 and ‘losing’ 3 euros for every other outcome. I’m trying to set them up for the concept of expected value, first reminding them how to calculate their average winnings over several rounds, and then moving on to show how we calculate the expected average without recourse to experiment. It would be nice, of course, for their experimental average to be recognizably close to this number. Not least since this particular lesson is being observed by the Berlin board of education, and the outcome will determine whether or not I can get a teaching permit as a foreigner.

“You are aware”, I ask a pair of students celebrating their fourth successful die roll in a row, “that you are ruining this experiment?” They laugh obligingly. In four pairs, a small group of students is spending a few minutes rolling dice, awarding themselves 12 euros for every 5 or 6 and ‘losing’ 3 euros for every other outcome. I’m trying to set them up for the concept of expected value, first reminding them how to calculate their average winnings over several rounds, and then moving on to show how we calculate the expected average without recourse to experiment. It would be nice, of course, for their experimental average to be recognizably close to this number. Not least since this particular lesson is being observed by the Berlin board of education, and the outcome will determine whether or not I can get a teaching permit as a foreigner.

In case they are reading this, I would like to emphasize that I plan all my lessons with care and forethought; but for this particular one, you can bet I prepared especially well and left nothing to chance. Except for the part I left to chance, that is. To be precise: I had neglected to calculate in advance how likely it was for the experimental average over roughly 80 games to diverge from the expected value by a potentially confusing amount. I relied on my intuition, which informed me that 80 is a large number.

Turns out it’s not that large after all. The probability of at least 50 cents divergence (which would bring the experimental average at least as close to another integer as to the expected value of 2 euros) is, I have now figured out, a whopping 56%. There was only a 0.6% chance for the experimental average to exceed, as it did, 4 euros, but I had also implicitly accepted a 4% chance that the results would have been closest to 0 or even negative. Just imagine the damage that would have caused.

It would not have been the first time for a probability experiment to result in my pleading with my students to trust the math over actual results they have just seen with their own eyes. The Monty Hall problem has been especially awkward at times. Read more »

by Ed Simon

Past the regal bronze lions of Trafalgar Square and Nelson’s towering and triumphant column, up the steps of the National Gallery and behind it’s porticoed, columned, Regency façade, and on the second floor in room 34, the same place where the museum displays William Hogarth’s formal, yet warm, portrait The Graham Children and Joseph Turner’s dramatic Dutch Boats in a Gale, is the most luminescent painting of the British Enlightenment, Joseph Wright of Derby’s 1768 masterpiece An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump. Fully six feet tall by eight feet wide, Wright’s composition depicts a wizardly natural philosopher framed in long gray locks and draped in a red coat not dissimilar to a robe, contrasted by flickering candlelight in an eerie chiaroscuro, with his hand atop the perfectly spherical chamber of a vacuum pump, inside of which is a fluttering Australian cockatoo – exotic at the time – right before the pressure of the exhumed air crushes it’s tiny avian lungs. A number of characters witness the scientific presentation; a gentleman in powdered wig and green jacket gives the experiment his rapt attention, two young lovers seem more concerned with each other, an assistant boy at the window closes the bird’s cage while bathed in the light of a full moon, and an elderly man seems to time the demise with an intricate pocket watch.

Demonstrations such as these had been conducted for more than a century by the time Wright put brush to canvas, and during the eighteenth-century they were performed as often by theatrical presenters with a paying audience as they were by scientists, yet the choice of test subjects in these experiments was frequently as cruel as the painter depicted. Robert Boyle, the chemist and philosopher who commissioned the scientist and engineer Robert Hooke to construct England’s first air pump in 1659, records the results of an experiment on a lark, where as oxygen was pumped out of the chamber the bird “began manifestly to droop and appear sick, and very soon after was taken with as violent and irregular convulsions,” so that the animal “threw herself over and over two or three time, and died with her breast upward, her head downwards, and her neck awry.” The dispassionate empiricism of Boyle’s report is in keeping with the mechanistic philosophy which dominated the Royal Society, the scientific organization established by King Charles II’s proclamation shortly after Restoration in 1663, and to which the chemist would donate the vacuum pump. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by David Winner

Coming from a Jewish family that arrived in America between the Slave Trade and the Holocaust, I thought that we were ethically in the clear, but researching my family story for Master Lovers, a book about my great-aunt Dorle’s love life in the 1930s, brought me face to face with famously fraught questions about evil and prejudice and the degree to which art and/or historical context can relieve us of its burdens. I thought of Ezra Pound’s and T.S. Eliot’s fascism, of course, Dustin Hoffman, Keven Spacy, and all the other actor/molesters but also Alice Walker’s interrogation of the Talmud, antisemitic or simply pro-Palestinian. And V.S. Naipaul, Indian from Trinidad, whose work (Bend in the River, India: A Wounded Civilization) skewered the post-colonial world.

Dorle Jarmel Soria, a Jewish woman who was a force in mid-century music, integral to both Leonard Bernstein and Maria Callas’s careers, and her husband Dario, who’d fled Rome after the Mussolini/Hitler pact, essentially raised my father. Once, he questioned Dorle about her friend soprano Elizabeth Schwarzkopf’s, close relationship (maybe affair) with Goebbels only to be rebuffed by the claim that “great art” lay “outside of politics.” And learning more about both her family and her lover, John Franklin Carter, whom she nearly married, revealed more dark associations. Ben Affleck convinced Henry Louis Gates not to reveal his enslaved-owning ancestors, but I – unfamous, little to lose – feel driven to out my family. Dorle, who smoked Benson & Hedges, drank gin and tonics, and traveled to Capri well into her nineties always recalled Graham Green’s beloved Aunt Augusta (Travels with my Aunt), but learning more about her made her seem more like Aunt Denver from Beloved, Heathcliff perhaps, someone haunted by their past.

By age thirty, I knew only a few “facts” about my Jewish family: our name did not come from Weiner, we were from somewhere near Poland, a distant relative translated the Declaration of Independence or was it the Constitution into Hebrew or Yiddish. Whereas my mother’s mother, born in Hapsburg Prague, compiled a genealogy going back centuries, my father’s Jewish side was apparently the family who fell to earth. Read more »

by Marie Snyder

I recently listened to a podcast of Dr. Louis Cozolino, a neuroscientist and psychoanalyst, discussing what he would teach if he were training psychotherapists. The first year would be phenomenology: the power of Carl Rogers’ perspective to train how to develop an alliance through reflective listening while keeping countertransference out of the session. The second year would be physiology: developmental neuroscience and the evolutionary history of brains and bodies. The third year might be called intersectionality: the interpenetration of the spectrum of options that affect clients – brain, mind, family, culture – and a reaction against therapy as a mere opiate to calm the oppressed and exploited. The final year would be on narratives and stories that we live by and on that half second that it takes our brain to construct our experience of the present and feed it back to us.

Cozolino insists that it’s not enough to just sit and listen to people vent. After developing a non-judgmental alliance with the client, therapists need to be “amygdala whisperers,” to be able to down modulate amygdala activation to stop any inhibitory effect on the parietal system that enables problem solving. In other words, they need to soothe anxieties while arousing enough interest for clients to be able to learn new information. Then it’s time to challenge the client’s old system of thinking, slowly and delicately, a little at a time, to help them expand previous conceptualizations of themselves and the world. There’s a necessary plan and a strategy to the sessions. Read more »

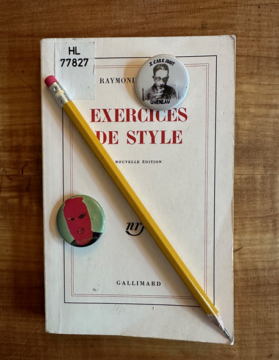

by Rafaël Newman

Notational

Notational

A Zurich-based translator answers an ad that reminds him of his youth and is sent several lapel pins, or buttons, bearing the likeness of a 20th-century French poet emblazoned with a motto. The creator of these buttons, a Chicago-based teacher, does not charge for his products, but asks only that they be worn. Their recipient is happy to comply.

The two men have not yet met in person; nevertheless, they discover a shared bond in their love of poetry and music, and begin to correspond. The second man eventually sends the first a new shipment of buttons (which he has been manufacturing together with his daughter), this time featuring the masked face of a contemporary Edinburgh-based artist and a new motto, once again free of charge. The first man agrees to wear these as well, especially since they give him the beribboned air of the dandy he once was.

The first man is then moved to distribute both series of buttons to people he meets during his travels, abroad and in his country of residence, on buses and at gatherings, and to photograph himself with these new recipients. He shares the photographs with the second man, as well as with the Edinburgh-based artist, who is, unlike the French writer, still alive. Read more »

by Bill Murray

First a note on the April 8th North American eclipse: Many people have seen a partial eclipse of the sun and wondered what all the fuss is about. The sky looks out of whack, things go all shimmery, you can see reflections of the partially occluded sun on leaves, animals act up, the sky darkens, maybe, and then it’s done.

That is a partial eclipse. The experience inside the narrow band of earth where the sun is entirely covered, called “totality,” is nothing like a partial eclipse. Two weeks from today North America experiences the longest path of totality for any eclipse this century.

The band of totality will be about 115 miles wide. Lots of people have the chance to get underneath it. If you’re interested, don’t settle for partial; go and find totality.

The longest totality in the US will be four minutes and 24 seconds. By comparison, the longest totality anywhere in the US for the 2017 eclipse lasted only two minutes and 41 seconds. These may sound like just statistics, but nearly five minutes of totality is a big deal. People pursue even a minute of totality across continents.

Totality is utterly unique. It’s something else entirely. Totality pulses with raw, brute, human-diminishing power. Read more »

Angus Deaton at the website of the IMF:

Economics has achieved much; there are large bodies of often nonobvious theoretical understandings and of careful and sometimes compelling empirical evidence. The profession knows and understands many things. Yet today we are in some disarray. We did not collectively predict the financial crisis and, worse still, we may have contributed to it through an overenthusiastic belief in the efficacy of markets, especially financial markets whose structure and implications we understood less well than we thought. Recent macroeconomic events, admittedly unusual, have seen quarrelling experts whose main point of agreement is the incorrectness of others. Economics Nobel Prize winners have been known to denounce each other’s work at the ceremonies in Stockholm, much to the consternation of those laureates in the sciences who believe that prizes are given for getting things right.

Economics has achieved much; there are large bodies of often nonobvious theoretical understandings and of careful and sometimes compelling empirical evidence. The profession knows and understands many things. Yet today we are in some disarray. We did not collectively predict the financial crisis and, worse still, we may have contributed to it through an overenthusiastic belief in the efficacy of markets, especially financial markets whose structure and implications we understood less well than we thought. Recent macroeconomic events, admittedly unusual, have seen quarrelling experts whose main point of agreement is the incorrectness of others. Economics Nobel Prize winners have been known to denounce each other’s work at the ceremonies in Stockholm, much to the consternation of those laureates in the sciences who believe that prizes are given for getting things right.

Like many others, I have recently found myself changing my mind, a discomfiting process for someone who has been a practicing economist for more than half a century. I will come to some of the substantive topics, but I start with some general failings.

More here.

Lawrence M. Krauss in Quillette:

Frans de Waal, one of the world’s preeminent primatologists, passed away on 14 March 2024, at the age of 75. He was the Charles Howard Candler Professor Emeritus of Psychology and former director of the Living Links Center for the Advanced Study of Ape and Human Evolution at the Emory National Primate Research Center.

Frans de Waal, one of the world’s preeminent primatologists, passed away on 14 March 2024, at the age of 75. He was the Charles Howard Candler Professor Emeritus of Psychology and former director of the Living Links Center for the Advanced Study of Ape and Human Evolution at the Emory National Primate Research Center.

His passing is a loss not just for his family and friends, but for science and society more broadly. De Waal’s death ends a career that showed what science can accomplish at its very best, by changing our perspective on ourselves and our place in the cosmos.

Frans was more than just a colleague and friend to me. He was a teacher. I count myself among the innumerable people who were impacted by his writing and lecturing in clear and explicit ways.

That is why I don’t feel that it is inappropriate for me to pen this brief memorial, even though I am a theoretical physicist and Frans was a primatologist.

More here.

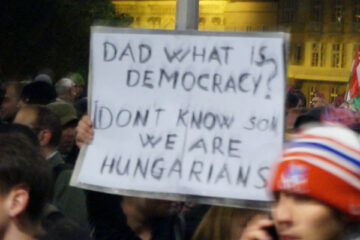

Holly Case in the Boston Review:

Last September an article on the front page of a leading Hungarian daily began, “The story of the ever-deepening refugee crisis is taking ever more unexpected turns.” A prominent Hungarian intellectual and former dissident, György Konrád, had come out in support of the efforts of the Hungarian government to build a wall to keep out newcomers and to cast them as economic opportunists rather than political refugees. In another corner of the Hungarian media, pundits were citing passages from The Final Tavern (A végső kocsma), a 2014 book by Holocaust survivor and 2002 Nobel laureate Imre Kertész, who passed away last month. In the book, Kertész was sharply critical of liberals’ welcoming attitude toward Muslim refugees and migrants. His and Konrád’s statements were registered with incredulity in the liberal press and with undisguised relish on the right.

Last September an article on the front page of a leading Hungarian daily began, “The story of the ever-deepening refugee crisis is taking ever more unexpected turns.” A prominent Hungarian intellectual and former dissident, György Konrád, had come out in support of the efforts of the Hungarian government to build a wall to keep out newcomers and to cast them as economic opportunists rather than political refugees. In another corner of the Hungarian media, pundits were citing passages from The Final Tavern (A végső kocsma), a 2014 book by Holocaust survivor and 2002 Nobel laureate Imre Kertész, who passed away last month. In the book, Kertész was sharply critical of liberals’ welcoming attitude toward Muslim refugees and migrants. His and Konrád’s statements were registered with incredulity in the liberal press and with undisguised relish on the right.

Anyone who has followed the serpentine trajectory of Hungarian politics since the controlled collapse of state socialism in 1989 might be forgiven for throwing their hands up in confusion. For more than two and a half decades, Hungarian political life has been a story of reversals.

More here.

Maniza Naqvi at Literary Hub:

Back in December 2016, I was sitting in my office at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., feeling unmoored and disheartened. Every day, I walked through Lafayette Park in front of the White House to get to my work. But lately, the noise had been so loud and ugly about the Muslim ban and building a wall. I was beginning to panic. What’s a person like me even supposed to do about this? Why am I even here?

Back in December 2016, I was sitting in my office at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., feeling unmoored and disheartened. Every day, I walked through Lafayette Park in front of the White House to get to my work. But lately, the noise had been so loud and ugly about the Muslim ban and building a wall. I was beginning to panic. What’s a person like me even supposed to do about this? Why am I even here?

I came from Pakistan thirty years ago for my job. I absolutely love my job. I get to work with national and local governments and villages to build social safety nets in order to reduce poverty. I get to design and supervise projects. I don’t actually do anything with my own hands, but I’m on the ground in many different countries, and I travel a lot. And now—as if flying while Muslim wasn’t fun enough—they’re going to ban me too?

I feel scattered all over the map. My writing helps to ground me. But still, I feel like I need a change. I need someone to throw me a lifeline.

More here.

Matt Reynolds in Wired:

In one way or another, the superrich have always been trying to extend their lives. Ancient Egyptians crammed their tombs with everything they’d need to live on in an afterlife not unlike their own world, just filled with more fun. In the modern era, the ultra-wealthy have attempted to live on through their legacies: sponsoring museums and galleries to immortalize their names.

In one way or another, the superrich have always been trying to extend their lives. Ancient Egyptians crammed their tombs with everything they’d need to live on in an afterlife not unlike their own world, just filled with more fun. In the modern era, the ultra-wealthy have attempted to live on through their legacies: sponsoring museums and galleries to immortalize their names.

Today’s elite take life-extension a lot more literally. Skipping neatly over the matter of Bryan Johnson’s nightly penis rejuvenation regime, billionaires like Jeff Bezos and Peter Thiel are sinking big money into the prospect of therapies to extend our mortal lives.

But how would one do that exactly? In his new book, Why We Die, Nobel Prize–winning biologist Venki Ramakrishnan breaks down the biology of aging to examine what potential humankind really has for life extension.

More here.

Eleanor Harris in New Scientist:

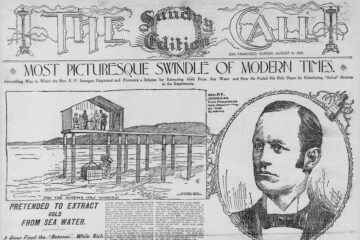

CRAP paper accepted by journal

CRAP paper accepted by journalAt New Scientist we love a good hoax, especially one that both amuses and makes a serious point about the communication of science. So kudos to Philip Davis, a graduate student at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, who got a nonsensical computer-generated paper accepted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

In 1996, American physicist Alan Sokal submitted a paper loaded with nonsensical jargon to the journal Social Text, in which he argued that quantum gravity is a social and linguistic construct. (Read Sokal’s paper). When the journal published it, Sokal revealed that the paper was in fact a spoof. The incident triggered a storm of debate about the ethics of Sokal’s prank.

More here.

Sometimes he’d be washing the car

. . . all by himself|

and he’d say, “Damn!”

or sweeping the last dry morsels of leaves

onto an old dust pan

saved just for outside

for when he was alone

in the silence of a summer afternoon

he’d say, “Damn!”

He didn’t go to his aubuelita’s funeral

He wasn’t there when his father died

He was with someone else he loved,

and he wasn’t there the moment she died

Y le pesaba, sabes?

An anvil of loneliness

would fall into his chest

and he’d say, “Damn!”

by César A Gonzalez

from Paper Dance, 55 Latino Poets

Persea Books, 1995

Y le pesaba, sabes?: and it weighed on him, you know?