Candida Moss in Time:

It is an unlikely success story. A first century religious leader named Jesus was brutally executed as a criminal in first century Jerusalem. His death should have ended the movement. He left behind him a ragtag group of poorly educated Aramaic-speaking fishermen and craftsmen; men with some street smarts who lacked resources, experience, or connections. And yet, tradition insists, this handful of men seeded the religion that would change the world.

It is an unlikely success story. A first century religious leader named Jesus was brutally executed as a criminal in first century Jerusalem. His death should have ended the movement. He left behind him a ragtag group of poorly educated Aramaic-speaking fishermen and craftsmen; men with some street smarts who lacked resources, experience, or connections. And yet, tradition insists, this handful of men seeded the religion that would change the world.

The improbability of Christianity’s success has always been part of its rhetorical power; how could this small group of misfits have succeeded against such odds? There is a lengthy intellectual tradition that attempts to explain the expansion, rise, and spread of Christianity from its beginnings in the Galilee to its ‘conquest’ of the Roman Empire. At least part of the answer, though neglected, is simple: The disciples had help. An overlooked aspect of the famous Road to Damascus story is how dangerous it was. The Apostle Paul’s vision of Christ left him in a perilous situation: newly blind and stranded several miles away from sustenance and shelter. It was only with the assistance of those in his entourage that he made it into the city and avoided an unpleasant death from starvation and dehydration. These helpers are almost invisible in the story, but they are critical to Paul’s success.

The contributions of invisible assistants go much further than their underappreciated but essential roles as local guides and travelling companions.

More here.

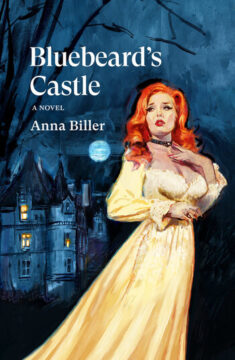

FILMMAKER ANNA BILLER begins her debut novel, Bluebeard’s Castle, with a warning: “Some husbands,” she writes, “are pussycats, some are dullards or harmless rogues, and some are Bluebeards.” Folklore and literary history are full of Bluebeards: Charles Perrault’s original fairy tale, two Brothers Grimm versions, Jane Eyre’s Mr. Rochester, modern retellings by writers, composers, and directors ranging from Georges Méliès and Béla Bartók to Helen Oyeyemi and Catherine Breillat. The elements of the story remain essentially the same: a young woman marries a mysterious, wealthy widower. Despite warnings (sometimes from her husband, sometimes from outsiders), she explores the recesses of his house and discovers that he has murdered all his former wives and keeps their bodies in a hidden chamber. The intrepid bride eventually reveals his secret, and the monster is punished—hacked to bits or burned alive. Though the story often has fantastic aspects—a talking bird, people who miraculously come back to life when their dismembered parts are reunited, a magical key or egg that proves that the wife found the chamber—true anxiety lies at its heart. Marriage is a gamble, it reminds us, and any husband could turn out to be a wife-killer.

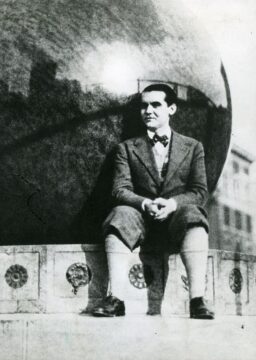

FILMMAKER ANNA BILLER begins her debut novel, Bluebeard’s Castle, with a warning: “Some husbands,” she writes, “are pussycats, some are dullards or harmless rogues, and some are Bluebeards.” Folklore and literary history are full of Bluebeards: Charles Perrault’s original fairy tale, two Brothers Grimm versions, Jane Eyre’s Mr. Rochester, modern retellings by writers, composers, and directors ranging from Georges Méliès and Béla Bartók to Helen Oyeyemi and Catherine Breillat. The elements of the story remain essentially the same: a young woman marries a mysterious, wealthy widower. Despite warnings (sometimes from her husband, sometimes from outsiders), she explores the recesses of his house and discovers that he has murdered all his former wives and keeps their bodies in a hidden chamber. The intrepid bride eventually reveals his secret, and the monster is punished—hacked to bits or burned alive. Though the story often has fantastic aspects—a talking bird, people who miraculously come back to life when their dismembered parts are reunited, a magical key or egg that proves that the wife found the chamber—true anxiety lies at its heart. Marriage is a gamble, it reminds us, and any husband could turn out to be a wife-killer. For a son of the titular city, reading Federico García Lorca’s Poet in New York is akin to curling into your lover, your nose dipped in the well of their collarbone, as they detail your mother’s various personality disorders. Yes, Federico, yes, my mother is thoroughly racist and takes every opportunity to remind me, her sometimes destitute child, about the silent cruelty of money. “At least you got to leave,” I want to tell him. “Imagine being stuck with her for the rest of your life.” He would likely understand my irrational attachment; after all, he was so consumed by Spain, its art and its politics, that his country would go on to swallow him whole.

For a son of the titular city, reading Federico García Lorca’s Poet in New York is akin to curling into your lover, your nose dipped in the well of their collarbone, as they detail your mother’s various personality disorders. Yes, Federico, yes, my mother is thoroughly racist and takes every opportunity to remind me, her sometimes destitute child, about the silent cruelty of money. “At least you got to leave,” I want to tell him. “Imagine being stuck with her for the rest of your life.” He would likely understand my irrational attachment; after all, he was so consumed by Spain, its art and its politics, that his country would go on to swallow him whole. People of different nationalities appear to vary in their use of hand gestures, according to a study that seems to reinforce the idea that Italians, in particular, “talk with their hands”.

People of different nationalities appear to vary in their use of hand gestures, according to a study that seems to reinforce the idea that Italians, in particular, “talk with their hands”.

It is a familiar story: a small group of animals living in a wooded grassland begin, against all odds, to populate Earth. At first, they occupy a specific ecological place in the landscape, kept in check by other species. Then something changes. The animals find a way to travel to new places. They learn to cope with unpredictability. They adapt to new kinds of food and shelter. They are clever. And they are aggressive.

It is a familiar story: a small group of animals living in a wooded grassland begin, against all odds, to populate Earth. At first, they occupy a specific ecological place in the landscape, kept in check by other species. Then something changes. The animals find a way to travel to new places. They learn to cope with unpredictability. They adapt to new kinds of food and shelter. They are clever. And they are aggressive. Branko Milanović’s Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War is an intellectual history of how leading economists since the 18th century, from Adam Smith to Karl Marx and beyond, have thought about income distribution and inequality.

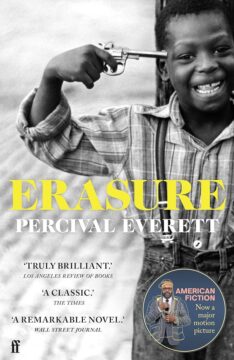

Branko Milanović’s Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War is an intellectual history of how leading economists since the 18th century, from Adam Smith to Karl Marx and beyond, have thought about income distribution and inequality. N

N Brown bears once roamed widely across Western Europe. But already by the Middle Ages, hunting and habitat degradation had pushed their populations to the east and north. In the Alpine region of Italy, at times with the backing of the state,

Brown bears once roamed widely across Western Europe. But already by the Middle Ages, hunting and habitat degradation had pushed their populations to the east and north. In the Alpine region of Italy, at times with the backing of the state,  In “

In “ Most members of the band subscribed to a live-fast-die-young lifestyle. But as they partook in the drinking and drugging endemic to the 1990s grunge scene after shows at the Whiskey a Go Go, Roxy and other West Coast clubs, the band’s guitarist, Valter Longo, a nutrition-obsessed Italian Ph.D. student, wrestled with a lifelong addiction to longevity.

Most members of the band subscribed to a live-fast-die-young lifestyle. But as they partook in the drinking and drugging endemic to the 1990s grunge scene after shows at the Whiskey a Go Go, Roxy and other West Coast clubs, the band’s guitarist, Valter Longo, a nutrition-obsessed Italian Ph.D. student, wrestled with a lifelong addiction to longevity.

A little over a year ago I published

A little over a year ago I published