by Jochen Szangolies

On May 11, 1997, chess computer Deep Blue dealt then-world chess champion Garry Kasparov a decisive defeat, marking the first time a computer system was able to defeat the top human chess player in a tournament setting. Shortly afterwards, AI chess superiority firmly established, humanity abandoned the game of chess as having now become pointless. Nowadays, with chess engines on regular home PCs easily outsmarting the best humans to ever play the game, chess has become relegated to a mere historical curiosity and obscure benchmark for computational supremacy over feeble human minds.

Except, of course, that’s not what happened. Human interest in chess has not appreciably waned, despite having had to cede the top spot to silicon-based number-crunchers (and the alleged introduction of novel backdoors to cheating). This echoes a pattern well visible throughout the history of technological development: faster modes of transportation—by car, or even on horseback—have not eliminated human competitive racing; great cranes effortlessly raising tonnes of weight does not keep us from competitively lifting mere hundreds of kilos; the invention of photography has not kept humans from drawing realistic likenesses.

Why, then, worry about AI art? What we value, it seems, is not performance as such, but specifically human performance. We are interested in humans racing or playing each other, even in the face of superior non-human agencies. Should we not expect the same pattern to continue: AI creates art equal to or exceeding that of its human progenitors, to nobody’s great interest? Read more »

Carlos Donjuan. Together Alone.

Carlos Donjuan. Together Alone.

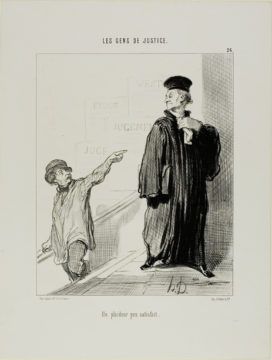

A philosopher and a stand-up comedian walk into a bar…the beginning of a joke? Or perhaps a history of humanity from the margins. The philosopher and the stand-up comedian are two figures that keep reappearing across the ages, cutting familiar silhouettes of odd bodies making odd claims about the world and its inhabitants.

A philosopher and a stand-up comedian walk into a bar…the beginning of a joke? Or perhaps a history of humanity from the margins. The philosopher and the stand-up comedian are two figures that keep reappearing across the ages, cutting familiar silhouettes of odd bodies making odd claims about the world and its inhabitants.

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric.

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric. The one regret of my life so far is never having seen Roger Federer play tennis in person. As Federer announced his retirement this year, I’ll never have the chance. The closest I came was the summer of 2017: I was in Italy and planned on flying to Stuttgart to see Federer play in a grass court tournament as preparation for Wimbledon. A few weeks before I was set to leave, I applied for a job at an English language school, largely at the behest of my girlfriend, who was unhappy with the fact that I was “studying” Italian in the mornings and flâning the streets in the afternoons, all while she spent long days toiling away as an unpaid intern in a law office, a common situation in Italy. I didn’t expect to get the job—I had little experience and no real credentials—but I would soon learn that neither of these things mattered, superseded as they were by my being a native speaker. I got the job and had to cancel my trip.

The one regret of my life so far is never having seen Roger Federer play tennis in person. As Federer announced his retirement this year, I’ll never have the chance. The closest I came was the summer of 2017: I was in Italy and planned on flying to Stuttgart to see Federer play in a grass court tournament as preparation for Wimbledon. A few weeks before I was set to leave, I applied for a job at an English language school, largely at the behest of my girlfriend, who was unhappy with the fact that I was “studying” Italian in the mornings and flâning the streets in the afternoons, all while she spent long days toiling away as an unpaid intern in a law office, a common situation in Italy. I didn’t expect to get the job—I had little experience and no real credentials—but I would soon learn that neither of these things mattered, superseded as they were by my being a native speaker. I got the job and had to cancel my trip.

Meis employed his dis- or un-layering style first in The Drunken Silenus: On Gods, Goats, and the Cracks in Reality.There Meis used Peter Paul Rubens’s 1620 painting, “The Drunken Silenus,” to expose the thinness of the membrane that separates mortality from immortality. Meis probes that membrane again in this second book, The Fate of the Animals. Here, he chooses Franz Marc’s 1913 painting, “The Fate of the Animals,” as a source for revealing or at least giving us a glimpse of the coming-into and going-out-of existence of all beings, including our own transient selves.

Meis employed his dis- or un-layering style first in The Drunken Silenus: On Gods, Goats, and the Cracks in Reality.There Meis used Peter Paul Rubens’s 1620 painting, “The Drunken Silenus,” to expose the thinness of the membrane that separates mortality from immortality. Meis probes that membrane again in this second book, The Fate of the Animals. Here, he chooses Franz Marc’s 1913 painting, “The Fate of the Animals,” as a source for revealing or at least giving us a glimpse of the coming-into and going-out-of existence of all beings, including our own transient selves. High school physics teachers describe them as featureless balls with one unit each of positive electric charge — the perfect foils for the negatively charged electrons that buzz around them. College students learn that the ball is actually a bundle of three elementary particles called quarks. But decades of research have revealed a deeper truth, one that’s too bizarre to fully capture with words or images.

High school physics teachers describe them as featureless balls with one unit each of positive electric charge — the perfect foils for the negatively charged electrons that buzz around them. College students learn that the ball is actually a bundle of three elementary particles called quarks. But decades of research have revealed a deeper truth, one that’s too bizarre to fully capture with words or images. I met Jerry when I was a pariah. I had repeatedly and publicly denounced the invasion of Iraq and, for my outspokenness, had been pushed out of The New York Times. I was receiving frequent death threats. My neighbors treated me as though I had leprosy. I had imploded my journalism career.

I met Jerry when I was a pariah. I had repeatedly and publicly denounced the invasion of Iraq and, for my outspokenness, had been pushed out of The New York Times. I was receiving frequent death threats. My neighbors treated me as though I had leprosy. I had imploded my journalism career. After they find dry ground for refuge, tie up surviving livestock, scan the ground for snakes and scorpions, queue, break queue and grab for food, plead for water, scream for tents, weep for loss, curse officials, lament fate — after all that, people whose lives have been upended by floods want to talk. I tell them I can’t do much. I am a researcher documenting and analyzing disaster impacts for various organizations, and it can be months before anyone even reads my reports. But sometimes, it’s enough for them to find someone who will listen.

After they find dry ground for refuge, tie up surviving livestock, scan the ground for snakes and scorpions, queue, break queue and grab for food, plead for water, scream for tents, weep for loss, curse officials, lament fate — after all that, people whose lives have been upended by floods want to talk. I tell them I can’t do much. I am a researcher documenting and analyzing disaster impacts for various organizations, and it can be months before anyone even reads my reports. But sometimes, it’s enough for them to find someone who will listen. Andrea Wulf’s substantial yet pacey new book concerns itself with a dazzling generation of German philosophers, scientists and poets who between the late 18th and early 19th centuries gathered in the provincial town of Jena and produced some of the most memorable works of European romanticism.

Andrea Wulf’s substantial yet pacey new book concerns itself with a dazzling generation of German philosophers, scientists and poets who between the late 18th and early 19th centuries gathered in the provincial town of Jena and produced some of the most memorable works of European romanticism.