Sughra Raza. Self Portrait at Gas Station, April 3, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait at Gas Station, April 3, 2022.

Month: April 2022

Why aren’t people paid according to their social contribution?

by Emrys Westacott

What should we do with our leisure? In his Politics, Aristotle identifies this as a fundamental philosophical question. Leisure, here, means freedom from necessary labor. If we have to spend much of our time working, or recuperating in order to work more, the question hardly arises. But if we are free from the yoke of necessity, how we answer the question will say much about our conception of the good life for a human being.

It is to be hoped that the question will one day become the primary question confronting humanity. This hope rests on the prospect of a world in which technological progress has advanced to such a degree that no one needs to work more than a few hours per week in order to enjoy a reasonably comfortable and secure existence. Before the industrial revolution such an idea was a mere fantasy; but given the rate of technological progress over the past two hundred years–and particularly in light of the recent digital revolution and the advent of what has been called “the second machine age”–the prospect of a much more leisurely life for those who want it is at least conceivable.

The fifteen-hour work week envisaged by John Maynard Keynes in “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” (1930) is hardly just around the corner, though. One problem, of course, is that there are some kinds of work that are not easily automated. Consider home care for the disabled, sick, and elderly. Machines are capable of cognitive tasks far beyond the ability of humans, yet many of the basic manual tasks caregivers perform are still very difficult for robots to replicate. Beyond that, though, caregivers also provide human contact and companionship. For machines to offer an adequate substitute for this takes us well into the realm of science fiction (which is not say into the realm of impossibility).

The deeper problem, though, is political rather than technological. Read more »

The Shame Machine: Author Cathy O’Neil Interviewed by Danielle Spencer

by Danielle Spencer

Cathy O’Neil’s The Shame Machine: Who Profits in the New Age of Humiliation (Crown) was released on March 22, 2022. O’Neil is the author of the bestselling Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (Crown 2016) which won the Euler Book Prize and was longlisted for the National Book Award. She received her PhD in mathematics from Harvard and has worked in finance, tech, and academia. She launched the Lede Program for data journalism at Columbia University and recently founded ORCAA, an algorithmic auditing company. O’Neil is a regular contributor to Bloomberg Opinion.

Danielle Spencer: Can you speak a bit about your background and what led you to write this book?

Cathy O’Neil: I’m a mathematician and a child of two mathematicians. Very nerd-centered childhood, where science was the religion of the household. They were otherwise atheists. I became a data scientist at some point, also a hedge fund analyst.

And then I started trying to warn people about the dangers of algorithms when we trust them blindly. I wrote a book called Weapons of Math Destruction, and in doing so I interviewed a series of teachers and principals who were being tested by this new-fangled algorithm called the value-added model for teachers. And it was high stakes. They were being denied tenure or even fired based on low scores, but nobody could explain their scores. Or shall I say, when I asked them, “Did you ask for an explanation of the score you got?” They often said, “Well, I asked, but they told me it was math and I wouldn’t understand it.”

And then I started trying to warn people about the dangers of algorithms when we trust them blindly. I wrote a book called Weapons of Math Destruction, and in doing so I interviewed a series of teachers and principals who were being tested by this new-fangled algorithm called the value-added model for teachers. And it was high stakes. They were being denied tenure or even fired based on low scores, but nobody could explain their scores. Or shall I say, when I asked them, “Did you ask for an explanation of the score you got?” They often said, “Well, I asked, but they told me it was math and I wouldn’t understand it.”

That was the first moment I thought, “Oh my God, shame is so powerful.” That was math shame, evidently, because it wouldn’t have worked on me. [laughs] I’m a mathematician. You’re not going to shame me on math. If you tell me I wouldn’t understand something because it’s math, I’d say, “Dude, buster, if you can’t explain it to me, that’s your problem—not mine.” I would just be bulletproof to math-shaming. Read more »

Review of How To Be Perfect

by Joseph Shieber

One of the best television comedies of the last decade was The Good Place. Over the course of four seasons, its creator, Michael Schur, and a phenomenal ensemble cast tackled topics that I had thought to be too arcane for network television. The so-called “trolley problem”? Kantian deontology? Utilitarianism? All in the series, served up with Schur’s finely honed comedic chops.

Despite having already had countless opportunities to explore the moral philosophical underpinnings of the show – on Vox alone Schur had a 100-minute interview with Ezra Klein on the moral philosophy of The Good Place and Dylan Matthews wrote an extended piece on “How the Good Place Taught Moral Philosophy to its Characters – And Its Creators” – Schur revisits this territory in his new book, How To Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral Question.

To which my first reaction was: Really, Michael Schur? You didn’t have enough to do creating and writing sitcoms for NBC? You just had to sell a philosophy book project to Simon & Schuster? I was almost enraged enough about his amateurish poaching on my professional bailiwick to sit down and craft an unputdownable pitch that would land me an exclusive, even more impressive deal with Universal Television than the one he signed. (Suck it, Schur!)

After I realized that I didn’t know the first thing about pitching a television series, I decided that my fall-back plan would be to read How To Be Perfect and then mock it with haughty disdain – not only at faculty cocktail receptions but also to my immediate friends and family … and here, at 3QD. So I read the book and I can now tell you it’s … really quite good, actually. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

The Talented Mr. Ripley and the American in Fiction

by Derek Neal

The character of the American abroad is an archetype in American fiction. By placing the American outside of his native country (usually in Europe), writers such as Henry James and James Baldwin were able to explore what constitutes American identity. More often than not, this identity is revealed in their novels not through what the identity contains, but in what it lacks.

The character of the American abroad is an archetype in American fiction. By placing the American outside of his native country (usually in Europe), writers such as Henry James and James Baldwin were able to explore what constitutes American identity. More often than not, this identity is revealed in their novels not through what the identity contains, but in what it lacks.

Indeed, the American in Europe is an empty vessel. Like the negative of an image, his surroundings are filled in, and the empty space where a person should be appears in outline. Thus, the American has the task of creating his own identity, of forging his own personality without the aid of history or culture but through sheer willpower alone. Whether this is a true representation of what it means to be American is irrelevant; this is the conception that writers have created in literature, giving rise to the myth of the American in Europe. Every time an American character enters Europe, they enter into this legacy, intentionally or not. It is a sort of self-orientalizing, as one can stereotype and mythologize oneself just as one can others.

Henry James and James Baldwin are two progenitors of this genre. For both, the American is a prodigal character and the return to Europe is a return home, to where his real roots lie. The trip to Europe, or the permanent move in some cases, is a search for self-knowledge, and similarly to the biblical Garden of Eden, Europe is often cast as a place of sin and danger, a place one might never escape from if one isn’t careful. Read more »

Yes, New Materials

by Mike O’Brien

“The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.” —Ecclesiastes 1:9

“Bullshit.” —Mike O’Brien 04-04-2022

It is a strange enough thing to collect knives. It is a step stranger still to collect sharpening stones; a further abstraction from reality, an auxiliary activity supporting a hobby which is itself a pantomime of preparedness and practicality. No matter. Once one is lodged firmly enough down a rabbit hole, the only options available are to hope for rescue, or to keep crawling deeper. I have clearly chosen the latter.

It is a strange enough thing to collect knives. It is a step stranger still to collect sharpening stones; a further abstraction from reality, an auxiliary activity supporting a hobby which is itself a pantomime of preparedness and practicality. No matter. Once one is lodged firmly enough down a rabbit hole, the only options available are to hope for rescue, or to keep crawling deeper. I have clearly chosen the latter.

The two collection are, in principle, complimentary. Or they would be, if my knife collection served any use that would engender a need for resharpening. As it is, they remain pristinely polished and razor sharp, to no wordly end. The fact that their polished edges are also sharp is almost incidental; the added challenge of making them both polished and sharp is an undertaking of curiosity, contemplative time-wasting, and vain self-overcoming. Still, it’s cheaper than collecting cars, with far less surface area over which to preen.

Of course, function is a factor in this appreciation. The marvel of an alloy hard enough to cut glass is that it can cut glass, in addition to the marvel of our ability to produce such an alloy. Diamonds can cut glass, but you can’t make a reasonably priced pocket knife out of diamonds (actually… well, it’s complicated). But an alloy that can cut glass, while being transformable into a shape of our choosing, and while also being re-sharpenable after God-know-what manner of use managed to dull it, is something more special still. It is an example of human ingenuity’s power to manipulate natural substances to suit whatever specialized application we may devise. It is awe-inspiring, both in the sense of wonderment and dread. Read more »

All the Glamour in Bein’ Sad

by Michael Abraham

I am leaving, and I am taking nothing.

I am leaving, and I am taking nothing.

I am leaving, and I am taking nothing, and there is a void inside me—a round, black sphere, like a planet, or like the absence of a planet where a planet should be. I am coming apart in the stress of it. I am borrowing money and time, bleeding my pride out my feet as I run from this bar to that bar to be anywhere, to be out. It is not only that I am sad. It is that I am depleted, that I have given all I can give, and, now, there is no gift left. There is no gift, as in, there is no special sense of possibility glimmering, of the impossible becoming possible through me. There was once this gift, this special sense, and now there is only its having been there, its having flown off to someone somewhere else.

***

I walk circles around this place that I am leaving, and I note all the little, special things, the daily clutter of being alive. I do not think about the time that I have spent here. I think only of leaving, of fluttering off like a moth—not like a butterfly, for I am not going off in a gay manner. I am somber like a moth. To be somber is not to be destitute; it is not to despair. There is a certain resignedness to being somber, a certain goodnaturedness. One who is somber is like falling water, carried forward irrepressibly, tinkling and shimmering as the onward pull of gravity does what it will always do, which is to draw on and downward—that is to say, to be somber is to face inevitability. One who is somber has an air about him, is better-off than other sad folks. One who is somber is like a moth. This is the best that I can explain it, the allure of the feeling that I am feeling. It is not enough to say that everything in my life is ending and starting again. That is true. But it is better to say that I am a small and fragile thing, a small and fragile thing with a certain gravitas, a certain solemnity, moving into the broader world to see what the broader world has in store, moving into the broader world because there is no choice, because it is in my nature to move. Fluttering, fluttering.

***

I don’t want to get into specifics because specifics muddy the water; they make complication where there might be the simplicity of feeling and all its affordances. Read more »

Monday Photo

The literary critic Hugh Kenner (whom I got to know a bit when I was an undergrad at Johns Hopkins) once wrote about the French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907) that he “…tired of flowers, and indulged in artificial flowers, and then tired of those and sought out real flowers so exotic they could pass for artificial.” This flower, in a restaurant I was in recently, reminded me of that. It was a real flower that could pass for artificial.

Mindful Murmurations II: Two Views From Nowhere

by Jochen Szangolies

In the previous essay, we saw the power of common knowledge to orchestrate collective action. We also saw that, generally, common knowledge is difficult to attain without a shared source of truth. This poses a problem for collective action: if we can’t be certain of whether others act alongside ourselves, taking action may be ill-advised; but then, it seems, we ought to conclude that the others will follow the same reasoning, and fail to act, when in fact, acting together would have been in everyone’s best interest.

I argued that, in such cases, the replacement for a common source of truth is to be found in the notion of faith: following William James, faith in a position is justified when evidence for the truth of that position is only available consequent to adopting it. For collective action, we each must have faith in the other’s actions; only then will we act ourselves, as will the others, and only by this will our faith be justified. Hence, having faith in other’s actions opens up a path to collective action where rational considerations might make it seem safer to abstain from action.

But the above glosses over an often underappreciated problem: facts, knowledge, or faith on its own doesn’t have any power to compel action. Just because things are this way or that doesn’t force me to do anything about it. Read more »

A Sputnik Education: Part 2

by Dick Edelstein

In Barcelona the daily scramble to deliver children to school results in terrible congestion in the upper part of the city, where the more economically privileged send their children. Watching this phenomenon brings back my own school days, when the most embarrassing thing any of us could imagine was being dropped off by parents. If such a thing were necessary for some unavoidable reason, the kids urged their parents to drop them a short distance away from the school so their peers wouldn’t see them getting out of the car. To be seen being coddled in this way was unimaginably embarrassing, almost as bad as having your mother show up to deliver a forgotten lunch box. Everything about parents tended to be embarrassing and much of the time we pretended not to have any. But there was a single exception to the drop-off rule. If the parents happened to own a 1956 Chevrolet, with its futuristic swept-wing design, then it was obligatory to be dropped off at school on some occasion, even if the ride was for only for a couple of blocks, so the other kids could look with sheer envy on this most prestigious possession. Read more »

In Barcelona the daily scramble to deliver children to school results in terrible congestion in the upper part of the city, where the more economically privileged send their children. Watching this phenomenon brings back my own school days, when the most embarrassing thing any of us could imagine was being dropped off by parents. If such a thing were necessary for some unavoidable reason, the kids urged their parents to drop them a short distance away from the school so their peers wouldn’t see them getting out of the car. To be seen being coddled in this way was unimaginably embarrassing, almost as bad as having your mother show up to deliver a forgotten lunch box. Everything about parents tended to be embarrassing and much of the time we pretended not to have any. But there was a single exception to the drop-off rule. If the parents happened to own a 1956 Chevrolet, with its futuristic swept-wing design, then it was obligatory to be dropped off at school on some occasion, even if the ride was for only for a couple of blocks, so the other kids could look with sheer envy on this most prestigious possession. Read more »

Charaiveti: Journey From India To The Two Cambridges And Berkeley And Beyond, Part 38

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Since my Chair was in International Trade, most of my teaching in Berkeley was in that field of Economics, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The undergraduate classes in Berkeley are large, and mine had sometimes more than 200 students, even though this course was meant mostly for later-year undergraduates. Large classes bring you in close touch (particularly in office hours) with a refreshing diversity of young people. But they also bring other kinds of experience.

Since my Chair was in International Trade, most of my teaching in Berkeley was in that field of Economics, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The undergraduate classes in Berkeley are large, and mine had sometimes more than 200 students, even though this course was meant mostly for later-year undergraduates. Large classes bring you in close touch (particularly in office hours) with a refreshing diversity of young people. But they also bring other kinds of experience.

In large crowded classrooms the borderlines were always a bit fuzzy–sometimes nearby pedestrians will saunter in just out of curiosity, to hear a funny-looking man speaking in a funny accent; some others were from the aimlessly-loitering often mentally-disabled street people. One day as I was teaching, one woman belonging probably to the latter group seated in a backbench suddenly stood up, looked at the ceiling for a minute and then gave out a piercing wail. As I was pondering how to handle this, fortunately for me she slowly walked out of the auditorium. Read more »

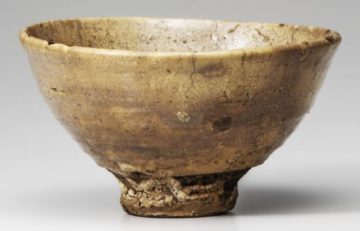

Christopher Hitchens and the Korean Tea-bowl

Leanne Ogasawara in Electrum Magazine:

A glance at Hobson-Jobson, the historical dictionary of Anglo-Indian words in use during the British rule in India, will show that the word “loot” comes into English from Hindi, ultimately deriving from Sanskrit. It entered the English language around the time of the Opium Wars, when the British were not just in India but also in China. This was when the 8th Earl of Elgin, James Bruce, was present at the sacking of the Summer Palace in Beijing. He was, incidentally, the son of the 7th Lord Elgin who removed the marbles from the Parthenon. James Bruce had this to say about loot:

A glance at Hobson-Jobson, the historical dictionary of Anglo-Indian words in use during the British rule in India, will show that the word “loot” comes into English from Hindi, ultimately deriving from Sanskrit. It entered the English language around the time of the Opium Wars, when the British were not just in India but also in China. This was when the 8th Earl of Elgin, James Bruce, was present at the sacking of the Summer Palace in Beijing. He was, incidentally, the son of the 7th Lord Elgin who removed the marbles from the Parthenon. James Bruce had this to say about loot:

There is a word called loot, which gives unfortunately a venial character to what would in common English be styled robbery.

Robbery or loot? Isn’t it all the same?

This winter, I took a postgraduate class at Stanford called Plundered Art: The History and Ethics of Art Collection. From Nebuchadnezzar, Nero and Napoleon to the Nazis and the present, we examined specific historic cases of art plundering and considered the ethics of such collections in museums to the present day as well as collecting in itself.

More here.

How the World’s Languages Evolved Over Time

Morten H. Christiansen and Nick Chater at Literary Hub:

Languages change continually and in wide variety of ways. New words and phrases appear, while others fall into disuse. Words subtly, or less subtly, shift their meanings or develop new meanings, while speech sounds and intonation change continually. Yet perhaps the most fundamental shift in language change is gradual conventionalization: patterns of communication are initially flexible, but over time they slowly become increasingly stable, conventionalized, and, in many cases, obligatory. This is spontaneous order in action: from an initial jumble increasingly specific patterns emerge over time.

Languages change continually and in wide variety of ways. New words and phrases appear, while others fall into disuse. Words subtly, or less subtly, shift their meanings or develop new meanings, while speech sounds and intonation change continually. Yet perhaps the most fundamental shift in language change is gradual conventionalization: patterns of communication are initially flexible, but over time they slowly become increasingly stable, conventionalized, and, in many cases, obligatory. This is spontaneous order in action: from an initial jumble increasingly specific patterns emerge over time.

The tendency toward increasing conventionalization occurs in all aspects of language, and it is largely a one-way street. Conventions become more rigid, not less. As in charades, when we face the same communicative challenge multiple times, our behavior becomes increasingly standardized. Once we’ve established a gesture for “Columbus” in one charade, we’ll stick with it in the unlikely event he comes up again, and the gesture will rapidly become simplified.

Yet when we face new communicative challenges, we retain the ability to be tremendously inventive—including the ability to rework and repurpose the conventions we’ve already established.

More here.

The Unlikely Persistence of Antonio Gramsci

Thomas Meaney in The New Republic:

Antonio Gramsci’s near-feral Sardinian childhood set him apart from most other leading communist revolutionaries of the interwar years, who tended to originate in cities. His father was imprisoned for petty embezzling as a state functionary in the Kingdom of Italy; his mother scraped by a living mending clothes. When Gramsci was four, a boil on his back began hemorrhaging, and he nearly bled to death. His mother bought a shroud and a small coffin, which stood in a corner of the house for the rest of his youth.

Antonio Gramsci’s near-feral Sardinian childhood set him apart from most other leading communist revolutionaries of the interwar years, who tended to originate in cities. His father was imprisoned for petty embezzling as a state functionary in the Kingdom of Italy; his mother scraped by a living mending clothes. When Gramsci was four, a boil on his back began hemorrhaging, and he nearly bled to death. His mother bought a shroud and a small coffin, which stood in a corner of the house for the rest of his youth.

As Gramsci’s latest biographer, the French historian Jean-Yves Frétigné, reports in To Live Is to Resist: The Life of Antonio Gramsci, Gramsci was buckled for hours each day into a leather harness contraption that hung from the rafters, intended to repair his spine. He hardened himself with tests of endurance, such as hammering his fingers with a stone until they bled. He kept a pet hawk, and idolized the Sardinian bandit Giovanni Tolu, who outfoxed the local Carabinieri. At school he was rebellious and insolent. Once, he had a dispute with a teacher who did not believe Gramsci had found a monstrous, snakelike lizard with feet. (He had: It was an ocellated skink.)

More here.

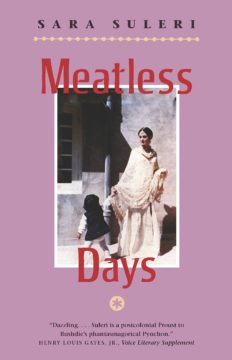

In Memoriam: My Brilliant Friend Sara

Azra Raza in Dawn:

My friend Professor Tahira Naqvi wrote in her condolence note: “I don’t think there is a book cover that has ever made a place in popular consciousness as that of Meatless Days. I can’t remember a book from my early days here that had as much of an impact as that brilliantly written memoir.”

My friend Professor Tahira Naqvi wrote in her condolence note: “I don’t think there is a book cover that has ever made a place in popular consciousness as that of Meatless Days. I can’t remember a book from my early days here that had as much of an impact as that brilliantly written memoir.”

As recently as this January, Sharon Cameron — a beloved friend and an exacting professor of English — read Meatless Days and had this to say: “I so admire the complex way SS weaves together family and Pakistani history and the nuanced way in which the narrative moves in and out, and then back around and at an angle through subjects newly given contour and life. SS is a very gifted writer.”

I read this to Sara over the telephone. Pleased, she remarked that the only other person who understood her “narrative weaving” was her friend and author David Lelyveld who, upon reading Meatless Days, exclaimed: “It moves like a ghazal!”

More here.

Going After That Pound of Flesh

Maureen Dowd in The New York Times:

So, the slap.

Why do people at the top of their careers snap and make wildly self-destructive moves that rip apart everything they have been working to build? In a blink, Will Smith went from Mr. Nice Guy on the verge of winning an Oscar to a crazed assailant in Satan’s grip. “At your highest moment, be careful. That’s when the devil comes for you,” Smith said in his acceptance speech, quoting what Denzel Washington told him minutes earlier to calm him down.

Why do people at the top of their careers snap and make wildly self-destructive moves that rip apart everything they have been working to build? In a blink, Will Smith went from Mr. Nice Guy on the verge of winning an Oscar to a crazed assailant in Satan’s grip. “At your highest moment, be careful. That’s when the devil comes for you,” Smith said in his acceptance speech, quoting what Denzel Washington told him minutes earlier to calm him down.

Let’s start with the fact that academy officials bungled the whole ugly affair. David Rubin, the president of the academy, should have gone over to Smith during the break and insisted on talking with him backstage. Then, he should have explained the academy’s position and had security guards escort the actor out of the building.

Instead, Hollywood’s big and powerful chickened out and asked Smith’s publicist to talk to him about leaving. His publicist! She no doubt told Smith to sit tight, which was, from a publicity point of view, good guidance. No wonder she was the first one he hugged when he walked offstage with his Oscar. Smith also got good advice from his team when on Friday he admitted he had “betrayed” the academy and resigned from the group — before he could be suspended. “I am heartbroken,” he said in a statement.

More here.

Six Nuns Came to India to Start a Hospital. They Ended Up Changing a Country

Jyoti Thottam in The New York Times:

In the spring of 1947, nothing about the future of India, its identity as a nation or the kind of country it would be, was certain. India would soon be free from British colonial rule, but it could not fulfill the basic needs — let alone the hopes and ambitions — of most of its people. That would require new institutions, new ideas, and men and women who were willing to take a chance on building them.

In the spring of 1947, nothing about the future of India, its identity as a nation or the kind of country it would be, was certain. India would soon be free from British colonial rule, but it could not fulfill the basic needs — let alone the hopes and ambitions — of most of its people. That would require new institutions, new ideas, and men and women who were willing to take a chance on building them.

India had been devastated by World War II and then partition, which split the country in two. By the end of 1948, two of India’s cities, Delhi and Mumbai, had each absorbed more than 500,000 refugees, and the country had endured violence, dislocation and food shortages on a mass scale. More than 20 million Indians lived under direct rationing, entitled to 10 ounces of grain a day. That was the period during which a handful of Catholic nuns from Kentucky chose to come to Mokama, a small town at a railroad junction in northern India on the southern banks of the Ganges River, to start a hospital.

More here.