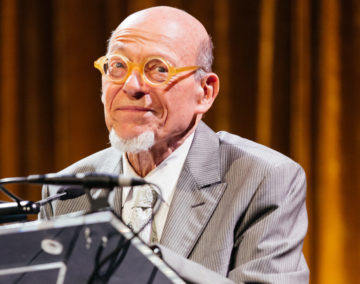

David Shenk in Delancey Place:

“‘It’s not that I’m so smart,’ Albert Einstein once said. ‘It’s just that I stay with problems longer.’

“‘It’s not that I’m so smart,’ Albert Einstein once said. ‘It’s just that I stay with problems longer.’

“Einstein’s simple statement is a clarion call for all who seek greatness, for themselves or their children. In the end, persistence is the difference between mediocrity and enormous success.

“The big question is, can it be taught? Can persistence be nurtured by parents and mentors?

“Boston College’s Ellen Winner insists not. Persistence, she argues, ‘must have an inborn, biological component.’ But the evidence indicates otherwise. The brain circuits that modulate a person’s level of persistence are plastic — they can be altered. ‘The key is intermittent reinforcement,’ says Robert Clonjnger, a Washington University biologist. ‘A person who grows up getting too frequent rewards will not have persistence, because they’ll quit when the rewards disappear.’

More here.

A few months before he died, Franz Kafka wrote one of his finest and saddest tales. In ‘The Burrow’, a solitary, mole-like creature has dedicated its life to building an elaborate underground home in order to protect itself from outsiders. ‘I have completed the construction of my burrow and it seems to be successful,’ the protagonist notes at the outset. Quickly, however, the creature’s confidence begins to wane: how can it know if its defences are working? How can it be certain?

A few months before he died, Franz Kafka wrote one of his finest and saddest tales. In ‘The Burrow’, a solitary, mole-like creature has dedicated its life to building an elaborate underground home in order to protect itself from outsiders. ‘I have completed the construction of my burrow and it seems to be successful,’ the protagonist notes at the outset. Quickly, however, the creature’s confidence begins to wane: how can it know if its defences are working? How can it be certain? The world can still hope to stave off the worst ravages of climate breakdown but only through a “now or never” dash to a low-carbon economy and society, scientists have said in what is in effect a final warning for governments on the climate.

The world can still hope to stave off the worst ravages of climate breakdown but only through a “now or never” dash to a low-carbon economy and society, scientists have said in what is in effect a final warning for governments on the climate. Those of us in the contemporary academy who are not liberals ought give an account of why not. This asymmetric burden falls on us, I believe, because the presumption is so strongly that one does fit within the broad confines of liberalism that if one does not explicitly identify out and explain why one has done so then two things may occur. First, people may reasonably presume on statistical grounds that your politics are as such and engage with you with this in mind. This will make intellectual back and forth, the lifeblood of our profession, frustratingly congealed — always having to go back and check unstated presuppositions half way through a conversation, never getting to the meat of things. Second, one allows whatever thinking one does to accrue to the greater glory of an ideology you reject. Since the natural presupposition is that whatever insights you achieve have been achieved through the lens of liberal ideology, it will seem that whatever is good in your work is evidence that liberalism can support and sustain that good. Since, by hypothesis, I am addressing myself to people who are not liberals, this is presumably something you wish to avoid.

Those of us in the contemporary academy who are not liberals ought give an account of why not. This asymmetric burden falls on us, I believe, because the presumption is so strongly that one does fit within the broad confines of liberalism that if one does not explicitly identify out and explain why one has done so then two things may occur. First, people may reasonably presume on statistical grounds that your politics are as such and engage with you with this in mind. This will make intellectual back and forth, the lifeblood of our profession, frustratingly congealed — always having to go back and check unstated presuppositions half way through a conversation, never getting to the meat of things. Second, one allows whatever thinking one does to accrue to the greater glory of an ideology you reject. Since the natural presupposition is that whatever insights you achieve have been achieved through the lens of liberal ideology, it will seem that whatever is good in your work is evidence that liberalism can support and sustain that good. Since, by hypothesis, I am addressing myself to people who are not liberals, this is presumably something you wish to avoid. EVERY YEAR, 40,000 PEOPLE

EVERY YEAR, 40,000 PEOPLE Since the early days of the pandemic, research has suggested that inflammation leads to significant respiratory distress and other organ damage, hallmarks of severe COVID-19. But scientists have struggled to pinpoint what triggers the inflammation.

Since the early days of the pandemic, research has suggested that inflammation leads to significant respiratory distress and other organ damage, hallmarks of severe COVID-19. But scientists have struggled to pinpoint what triggers the inflammation. “I knew in Goon Squad that Bix would invent social media,” Jennifer Egan says of her character Bix Bouton, who returns from her Pulitzer Prize–winning

“I knew in Goon Squad that Bix would invent social media,” Jennifer Egan says of her character Bix Bouton, who returns from her Pulitzer Prize–winning  Tropical forests have a crucial role in cooling Earth’s surface by extracting carbon dioxide from the air. But only two-thirds of their cooling power comes from their ability to suck in CO2 and store it, according to a study

Tropical forests have a crucial role in cooling Earth’s surface by extracting carbon dioxide from the air. But only two-thirds of their cooling power comes from their ability to suck in CO2 and store it, according to a study Do the Ukraine war and the action of the United States, the EU and the UK spell the

Do the Ukraine war and the action of the United States, the EU and the UK spell the  The agility of Donne’s imagination and the sheer pyrotechnic weirdness of his writings have made him both irresistibly attractive to biographers – who wouldn’t want to understand the man behind poems like this? – and particularly elusive of biographical scrutiny: what set of facts could possibly help to explain such a person? Katherine Rundell’s excellent Super-Infinite approaches Donne with keen and frank awareness of these temptations and the pitfalls they conceal. She recognises the double bind in which Donne’s works place his readers: they are conspicuously difficult and erudite, demanding depth of knowledge, intensity of attention and speed of thought from those who would follow them, but bringing knowledge to bear upon their quicksilver shifts and spurts of imagination can feel like ramming a pin through the body of a particularly beautiful butterfly in order to taxonomise it. Rundell is scrupulously polite about R C Bald’s ‘spectacularly detailed’ life of Donne, the standard scholarly biography, calling it ‘the bedrock of this book’ in a footnote, but there has surely never been a duller life of a more exciting poet. Knowledge may be necessary, but it can be like an anvil dropped on the head of a mischievous cartoon character, stunning it briefly into passive silence.

The agility of Donne’s imagination and the sheer pyrotechnic weirdness of his writings have made him both irresistibly attractive to biographers – who wouldn’t want to understand the man behind poems like this? – and particularly elusive of biographical scrutiny: what set of facts could possibly help to explain such a person? Katherine Rundell’s excellent Super-Infinite approaches Donne with keen and frank awareness of these temptations and the pitfalls they conceal. She recognises the double bind in which Donne’s works place his readers: they are conspicuously difficult and erudite, demanding depth of knowledge, intensity of attention and speed of thought from those who would follow them, but bringing knowledge to bear upon their quicksilver shifts and spurts of imagination can feel like ramming a pin through the body of a particularly beautiful butterfly in order to taxonomise it. Rundell is scrupulously polite about R C Bald’s ‘spectacularly detailed’ life of Donne, the standard scholarly biography, calling it ‘the bedrock of this book’ in a footnote, but there has surely never been a duller life of a more exciting poet. Knowledge may be necessary, but it can be like an anvil dropped on the head of a mischievous cartoon character, stunning it briefly into passive silence. Reading was Richard’s primary occupation. His New York apartment was covered in books, floor to ceiling, interrupted only by a desk, a few places to sit, a bed in a book-lined alcove (which was also home to Mildred, Richard’s life-size stuffed gorilla), and the bathroom, adorned with dozens of small portraits of famous writers, glaring at anyone who dared use the toilet. The kitchen was an afterthought—mostly a place to store kibble for Gide, his eccentric French bulldog, since Richard almost always ate out. I used to care for Gide when Richard traveled, so I was once there on his return from a trip to Europe with his husband, the artist David Alexander; the souvenir Richard was most excited to show off was a gargantuan copy—I think in French, though perhaps in the original Italian—of Leopardi’s Zibaldone, which had not yet been translated into English in its entirety. Finally he could read it! New books were among the major events of his life. By his door was always a growing stack of books to sell to the Strand; at some point David had introduced the rule that for every new book that came in, one had to go out.

Reading was Richard’s primary occupation. His New York apartment was covered in books, floor to ceiling, interrupted only by a desk, a few places to sit, a bed in a book-lined alcove (which was also home to Mildred, Richard’s life-size stuffed gorilla), and the bathroom, adorned with dozens of small portraits of famous writers, glaring at anyone who dared use the toilet. The kitchen was an afterthought—mostly a place to store kibble for Gide, his eccentric French bulldog, since Richard almost always ate out. I used to care for Gide when Richard traveled, so I was once there on his return from a trip to Europe with his husband, the artist David Alexander; the souvenir Richard was most excited to show off was a gargantuan copy—I think in French, though perhaps in the original Italian—of Leopardi’s Zibaldone, which had not yet been translated into English in its entirety. Finally he could read it! New books were among the major events of his life. By his door was always a growing stack of books to sell to the Strand; at some point David had introduced the rule that for every new book that came in, one had to go out. “Within a few years owning a car,” writes Bryan Appleyard in this entertainingly forthright history, “might seem as eccentric as owning a train or a bus. Or perhaps it will simply be illegal.” Although Appleyard’s intention is to document a way of life that he believes is passing, his book is not a lament or a eulogy, nor really a celebration, but instead an acknowledgment of the extraordinary cultural and environmental impact the car has had on this planet in the last 135-plus years.

“Within a few years owning a car,” writes Bryan Appleyard in this entertainingly forthright history, “might seem as eccentric as owning a train or a bus. Or perhaps it will simply be illegal.” Although Appleyard’s intention is to document a way of life that he believes is passing, his book is not a lament or a eulogy, nor really a celebration, but instead an acknowledgment of the extraordinary cultural and environmental impact the car has had on this planet in the last 135-plus years. The tank looked empty, but turning over a shell revealed a hidden octopus no bigger than a Ping-Pong ball. She didn’t move. Then all at once, she stretched her ruffled arms as her skin changed from pearly beige to a pattern of vivid bronze stripes. “She’s trying to talk with us,” said Bret Grasse, manager of cephalopod operations at the Marine Biological Laboratory, an international research center in Woods Hole, Mass., in the southwestern corner of Cape Cod.

The tank looked empty, but turning over a shell revealed a hidden octopus no bigger than a Ping-Pong ball. She didn’t move. Then all at once, she stretched her ruffled arms as her skin changed from pearly beige to a pattern of vivid bronze stripes. “She’s trying to talk with us,” said Bret Grasse, manager of cephalopod operations at the Marine Biological Laboratory, an international research center in Woods Hole, Mass., in the southwestern corner of Cape Cod. Beliefs about the essential goodness or badness of human beings have been at the heart of much political theory.

Beliefs about the essential goodness or badness of human beings have been at the heart of much political theory.