Month: December 2021

Modernity And The Fall

Caitrin Keiper at The New Atlantis:

In Susanna Clarke’s fantasy novel Piranesi, we meet an exceptionally innocent narrator who dates his life from a sublime encounter he has with an albatross. As the bird comes swooping toward him, he has a vision that they could merge into a being he knows of but has never seen — “an Angel!” — and imagines how he will fly through the world with “messages of Peace and Joy.” When he and the albatross do not become one, he instead offers it a gracious welcome, and helps it gather materials for a warm, dry nest. He sacrifices his own resources to do this, “but what is a few days of feeling cold compared to a new albatross in the World?” From this point on, his detailed notebooks refer to “the Year the Albatross came to the South-Western Halls.”

In Susanna Clarke’s fantasy novel Piranesi, we meet an exceptionally innocent narrator who dates his life from a sublime encounter he has with an albatross. As the bird comes swooping toward him, he has a vision that they could merge into a being he knows of but has never seen — “an Angel!” — and imagines how he will fly through the world with “messages of Peace and Joy.” When he and the albatross do not become one, he instead offers it a gracious welcome, and helps it gather materials for a warm, dry nest. He sacrifices his own resources to do this, “but what is a few days of feeling cold compared to a new albatross in the World?” From this point on, his detailed notebooks refer to “the Year the Albatross came to the South-Western Halls.”

The man called Piranesi (though he correctly senses that is not really his name) is one of only two human inhabitants in what he calls the House, a labyrinth of marble halls and ocean life and statues of people and nature and legend. Piranesi’s many energies are devoted to exploring and documenting the House with care.

more here.

“It may be Alright in Theory but it doesn’t Work in Practice”

by Martin Butler

This is what my dad used to say when as an idealistic teenager I would propose various utopian schemes for reforming society. I suspect it encapsulates the response of many who view themselves as grounded in the ‘real world’. We might want to dismiss the saying as crude anti-intellectualism, but it’s worth further examination if only because it’s such a widely held sentiment.[1]

As a teenager my first thought in response to this was that if a theory doesn’t work in practice, it can’t be ‘alright’. The only test of a theory, I thought, is that it should have a viable practical application. This makes sense when we consider scientific theories: it is simply nonsensical to say gravity might be alright in theory but not in practice. It’s only alright in theory because it works in practice. Einstein’s theory of general relativity only became more than ‘just a theory’ when measurements taken during the solar eclipse of 1919 corroborated its predictions. It was clearly alright in practice, therefore also in theory. Of course, there are other ways in which a theory might at least appear to be ‘alright’ – it might, for example, be an elegant theory or possess a satisfying simplicity. Perhaps this is all those who use the saying mean, although I think there are more interesting issues lurking in the background, especially when we come to abstract political, social or moral theories. Read more »

Monday Poem

Woke up, fell out of bed,

Dragged a comb across my head

Found my way downstairs and drank a cup,

And looking up I noticed (it) was late

………………—John Lennon, A Day in the Life

Mystical Fun

Jim Culleny

9/14/16

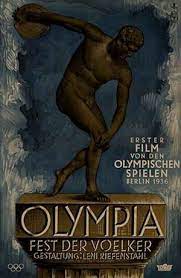

Defining Propaganda and Ideology

by Joseph Shieber

Within the last few weeks, a high ranking official within the municipal government in Philadelphia resigned for making anti-Semitic remarks. Among those remarks, apparently, was the claim that the Holocaust film Schindler’s List was “Jewish propaganda.”

It’s probably a sign that I’ve been thinking about these issues for too long, but my first thought was, Why is it an insult to call something propaganda? What’s wrong with propaganda?

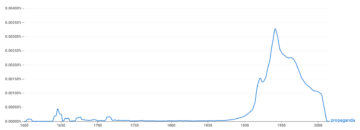

The term “propaganda” itself stems only from the 17th century, when the Catholic Church formed the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide, a committee of cardinals responsible for the Church’s efforts to proselytize non-believers. The use of the term as a denotation for a strategy for influencing public opinion, however, only really exploded at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, as journalism became professionalized. It was then that practitioners, theorists and politicians began to reflect on the ways in which governments and other organizations could use media outlets to shape public opinion.

Here, for example, is the Google Ngram viewer of “propaganda” from 1600 to 2016:

Although the term is less than 400 years old, the phenomenon of propaganda is far older. The pyramids of Egypt, to take one example, are propagandistic, attesting to the power of the Pharaohs who could enslave thousands of people to erect them. (But see this.) So are the coins stamped with the likenesses of the Roman emperors and circulated throughout the Mediterranean.

Given its ubiquity as a phenomenon, it is surprising how meager the theoretical discussion of propaganda actually is. Although there was a surge in works attempting to treat propaganda as a subject of academic inquiry in the first half of the 20th century, since then there have been comparatively few studies of propaganda, apart from largely historical assessments. Read more »

Poem

Moth

A tap at the black glass,

discrete, but urgent.

A night moth, big as

a beech leaf, burnt,

brown, wind-ripped,

flaps in its frame,

peddling high-step,

then ascends the pane

as if winched, hovers

against the jamb,

plunges free fall, recovers,

begins again to climb,

then crabs sidewards

across the window,

drifts back, then upwards

again, this time slow,

as if searching the glass

for a seam to pick,

for some sort of puchase,

a fault line to attack,

to work on, to ply

its cotton-thin but

infinite industry

against and force apart

the bruisingly firm

petals of this strange

rectangular bloom,

first seen as a wink of orange

inviting it down

from the dark pasture

and across the lawn

to the one-eyed house where

it now, with more hope

than method, more drive

than design, gropes

at the glass as it strives

to leave behind the night,

to cross the invisble thin

barrier, and taste the bright

sweet life of the world within.

by Emrys Westacott

Mind The Matter: Consciousness As Self-Representational Access

by Jochen Szangolies

There are two main problems that bedevil any purported theory of the mind. The first is the Problem of Intentionality: the question of how mental states can come to be about, or refer to, things in the world. The second is the Problem of Phenomenal Experience: the question of how come there is ‘something it is like’ to be in a certain mental state, how mental content is something that appears to us in a certain way (this is also often referred to as simply the ‘Hard Problem’).

These problems are often assumed to be separate issues. However, in a recent article published in the journal Erkenntnis (pre-print version), I propose that one can make progress on the Problem of Intentionality, but at the expense of leaving the Hard Problem unsolvable—indeed, making the task of ‘solving’ it a kind of conceptual confusion: an attempt of capturing the non-structural, non-relational in terms of structure and relation.

In a nutshell, I propose that states of mind are intentional because, through what I call the von Neumann-process, their own properties are represented to themselves; to the extent that these properties then reflect those of objects in the world, the properties of those objects are available to them. Hence, a mental state becomes ‘about’ the world by being, first and foremost, about itself. Read more »

Perceptions

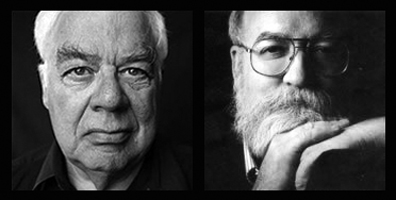

The Philosopher and Pain: The Case of Rorty and Dennett

by Guy Elgat

A couple of weeks ago, on the pages of this website, some critical comments on Richard Rorty’s general argumentative style were made, and, sympathetic to these comments, this inspired me to join the discussion with some criticism of Rorty of my own and, while I am at it, throw in some criticism of Daniel Dennett, for, as will be seen, they both have some mindboggling and implausible things to say about the experience of pain. This, in my view, stems from one of the things they have in common despite their many and substantial differences, namely, their deep animosity to anything Cartesian.

A couple of weeks ago, on the pages of this website, some critical comments on Richard Rorty’s general argumentative style were made, and, sympathetic to these comments, this inspired me to join the discussion with some criticism of Rorty of my own and, while I am at it, throw in some criticism of Daniel Dennett, for, as will be seen, they both have some mindboggling and implausible things to say about the experience of pain. This, in my view, stems from one of the things they have in common despite their many and substantial differences, namely, their deep animosity to anything Cartesian.

The experience of pain, and indeed any qualitative experience at all – what is referred to in philosophical circles with that ugly word “qualia” – is the bugbear of all hard-nosed and tough-minded philosophers who, enamored of the methods and results of the sciences, seek to eliminate or reduce any and every residue of the mental that is subjective, first-person, infallible, private, intrinsic, or indeed, qualitative. These properties, characteristic of the Cartesian mind, though certainly not conceived by Descartes in these very terms, threaten the scientific image of the world where everything is supposed to be objective, quantitative, extrinsic, and open to experimentation, verification and revision. As such, qualitative, first-person experiences are to be, if not explained away, expelled or expunged from any respectable philosophy. And while Rorty himself was not in any way a science-enthusiast, he shared Dennett’s scientifically-infused critical attitude to the Cartesian mind: the Cartesian legacy in the philosophy of mind must (not without some glee) be quashed, no matter the philosophical cost. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

A Sense of Place

by Derek Neal

One of those mysterious concepts that we use as a criterion for judging a novel or film is a “sense of place.” I call it mysterious because it’s so often poorly defined—we recognize it because we can feel it, but what goes into creating it? How can one go about transporting a reader, for example, into a time and place via text? I’m under the impression that if asked this question, most people would mention things like using the five senses to describe a character’s impressions of his or her surroundings, or providing detail via adjectives and adverbs. This may be a gross generalization, but it’s what I’ve gathered from my experience in creative writing courses. It’s also the sense I get from reading short stories in literary journals, which seem to be where aspiring writers publish their attempts at fiction. I often find this writing technically good, but lifeless; it has all the components of effective writing but doesn’t add up to anything compelling. I don’t mean to suggest that I could do better, but I do know what I enjoy reading and what I don’t.

One of those mysterious concepts that we use as a criterion for judging a novel or film is a “sense of place.” I call it mysterious because it’s so often poorly defined—we recognize it because we can feel it, but what goes into creating it? How can one go about transporting a reader, for example, into a time and place via text? I’m under the impression that if asked this question, most people would mention things like using the five senses to describe a character’s impressions of his or her surroundings, or providing detail via adjectives and adverbs. This may be a gross generalization, but it’s what I’ve gathered from my experience in creative writing courses. It’s also the sense I get from reading short stories in literary journals, which seem to be where aspiring writers publish their attempts at fiction. I often find this writing technically good, but lifeless; it has all the components of effective writing but doesn’t add up to anything compelling. I don’t mean to suggest that I could do better, but I do know what I enjoy reading and what I don’t.

Another way to create a sense of place, and this is my preferred method as a reader, is to include an abundance of proper nouns relating to real places, streets, and buildings. I’m not sure why this works. It would seem that this way of writing should only make sense for readers who have visited the places being mentioned, while readers unfamiliar with the locations might feel something lacking and be unable to create an image in their minds. But do we ever really create an accurate image of what we’re reading, or do the words on the page merge with our own ideas and create something unique in the mind of each individual reader? I’d say it’s the latter. Read more »

Monday Photo

Historical Memory 3: The Past and Ireland’s Uncomfortable Present

by Dick Edelstein

The notion of historical memory has to do with the ways in which social groups and nations construct and identify with particular narratives about historical periods or events. This is the third in a series of four articles on this topic. The first two can be found here. In the first I discussed the treatment of archival information on Spanish Civil War casualties and victims, and the activities related to that issue undertaken by the Spanish NGO Innovation & Human Rights. In the second I examined the activities of Fired! Irish Women Poets and the Canon, a collective that worked to redress the exclusion of Irish women writers from the historical record. The present article is not the final one, as I previously announced, because my topic became too broad to fit comfortably in a single piece. In the concluding column, which will be published here in four weeks, I will consider various manifestations in Spain of the issue of historical memory, and I will discuss the perennial conflict between the need to remember and the need to forget, as well as conflicts that arise when different groups appeal to the right to remember.

In this article I discuss several of the embarrassingly large number of recent situations in Ireland in which the issue of historical memory has irrupted into the news and the public awareness. Besides the Fired! movement and the previously discussed Waking the Feminists campaign, these occurrences include the exploitation and abuse of unwed mothers at the Magdalene Laundries, the secret burial of babies in Tuam, the Roman Catholic church cover-up of sexual abuse by priests and nuns, and perennial issues related to British colonial oppression and sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland. Read more »

Charaiveti: Journey From India To The Two Cambridges And Berkeley And Beyond, Part 22

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Though I decided to go back to India, which institution I’d join there took some more time to determine. I had a standing invitation from K.N. Raj at the Delhi School of Economics. Even before I left MIT he asked me to teach a course in MIT’s summer-vacation period. I went and taught part of a course, which had good students (including Amitava Bose, who in his later professional life became close to me, served as a Director of the Indian Institute of Management in Kolkata, and finally lost his long battle against cancer). But I soon found out that the only job Raj could offer me was that of a Readership (Associate Professorship), as a full Professorship was not yet vacant. Amartya-da advised me against accepting a Readership, since in Indian universities there could be ‘many a slip’ even when a Professorship became vacant. I went back to MIT after the vacation, and soon after I got a message from T.N. Srinivasan of the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) in Delhi, offering a full Professorship there, which I accepted.

Though I decided to go back to India, which institution I’d join there took some more time to determine. I had a standing invitation from K.N. Raj at the Delhi School of Economics. Even before I left MIT he asked me to teach a course in MIT’s summer-vacation period. I went and taught part of a course, which had good students (including Amitava Bose, who in his later professional life became close to me, served as a Director of the Indian Institute of Management in Kolkata, and finally lost his long battle against cancer). But I soon found out that the only job Raj could offer me was that of a Readership (Associate Professorship), as a full Professorship was not yet vacant. Amartya-da advised me against accepting a Readership, since in Indian universities there could be ‘many a slip’ even when a Professorship became vacant. I went back to MIT after the vacation, and soon after I got a message from T.N. Srinivasan of the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) in Delhi, offering a full Professorship there, which I accepted.

I was somewhat familiar with the Kolkata headquarters of ISI, a world-class center for statistics those days, with a leafy campus, but I did not know much about the Planning Unit of ISI in Delhi where I was to work. It did not have a campus at that time, it was originally linked to the Indian Planning Commission, which was housed in a large Government building, called Yojana Bhavan. When P.C. Mahalanobis, the distinguished statistician and founder-director of ISI was a member of the Planning Commission, from 1955 to 1967, he wanted this unit to provide research input to the planning process. By the time I joined ISI Mahalanobis had left the Planning Commission, and this unit turned itself into a general research outfit, though later some teaching of post-graduate students started. It continued being housed in that Government building until a new campus for the Delhi branch of ISI was completed. Read more »

Treason of the Intellectuals

Mark Lilla in Tablet:

Certain books never live up to their memorable titles. Others do, but not in the way their authors might have anticipated. Julien Benda’s The Treason of the Intellectuals, an essential intervention in 20th-century debates about intellectual responsibility, is the second sort of book. Cast into the agitated waters of European politics between the two world wars, it still floats ashore every decade or so, attracting readers with its stirring call to the independent life of the mind, free from the lures of power and authority. It is essential reading. Ever since the book’s publication in 1927, its argument has been taken up by writers of very different political stripes in very different historical circumstances. In the 1930s communist intellectuals denounced their fascist counterparts as traitors to the truth; liberals levied the same charge against communists and fellow travelers during the Cold War, only to find themselves then put in the dock by progressives and neoconservatives and now populists. Treason is one of those books that serve both as a lens for discerning the present and a mirror reflecting the image of those who appeal to it.

Certain books never live up to their memorable titles. Others do, but not in the way their authors might have anticipated. Julien Benda’s The Treason of the Intellectuals, an essential intervention in 20th-century debates about intellectual responsibility, is the second sort of book. Cast into the agitated waters of European politics between the two world wars, it still floats ashore every decade or so, attracting readers with its stirring call to the independent life of the mind, free from the lures of power and authority. It is essential reading. Ever since the book’s publication in 1927, its argument has been taken up by writers of very different political stripes in very different historical circumstances. In the 1930s communist intellectuals denounced their fascist counterparts as traitors to the truth; liberals levied the same charge against communists and fellow travelers during the Cold War, only to find themselves then put in the dock by progressives and neoconservatives and now populists. Treason is one of those books that serve both as a lens for discerning the present and a mirror reflecting the image of those who appeal to it.

The $11-billion Webb telescope aims to probe the early Universe

Alexandra Witze in Nature:

Lisa Dang wasn’t even born when astronomers started planning the most ambitious and complex space observatory ever built. Now, three decades later, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is finally about to launch, and Dang has scored some of its first observing time — in a research area that didn’t even exist when it was being designed.

Lisa Dang wasn’t even born when astronomers started planning the most ambitious and complex space observatory ever built. Now, three decades later, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is finally about to launch, and Dang has scored some of its first observing time — in a research area that didn’t even exist when it was being designed.

Dang, an astrophysicist and graduate student at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, will be using the telescope, known as Webb for short, to stare at a planet beyond the Solar System. Called K2-141b, it is a world so hot that its surface is partly molten rock. She is one of dozens of astronomers who learnt in March that they had won observing time on the telescope. The long-awaited Webb — a partnership involving NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) — is slated to lift off from a launch pad in Kourou, French Guiana, no earlier than 22 December.

More here.

How—and Why—America Criminalizes Poverty

Tony Messenger in Literary Hub:

Nearly every state in the country has a statute—often called a “board bill” or “pay-to-stay” bill—that charges people for time served. In Missouri and Oklahoma—and in states on both coasts and in the Deep South—these pay-to-stay bills follow defendants arrested initially for small offenses like petty theft or falling behind in child support. Nearly 80 percent of these defendants live below the federal poverty line, meaning they make less than $12,880 a year if they are single, or $21,960 if they are a family of three.

Nearly every state in the country has a statute—often called a “board bill” or “pay-to-stay” bill—that charges people for time served. In Missouri and Oklahoma—and in states on both coasts and in the Deep South—these pay-to-stay bills follow defendants arrested initially for small offenses like petty theft or falling behind in child support. Nearly 80 percent of these defendants live below the federal poverty line, meaning they make less than $12,880 a year if they are single, or $21,960 if they are a family of three.

They are the working poor: getting by on minimum wage jobs at the local dollar store; seasonal construction workers who get roofing jobs after tornado season; or, like Bergen, they are unemployed, unable to escape the combination of drug offenses and a criminal justice system that follows them everywhere. In some places, like Rapid City, South Dakota, the charges for jail time are small, $6 a day; in other places, like Riverside County, California, they have been as high as $142 a day. For people of little means, these court debts are an albatross they cannot escape or ignore.

More here.

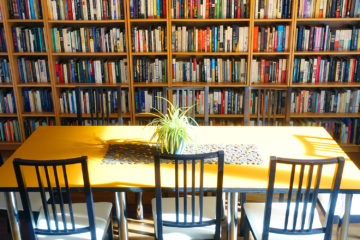

The Best Books of 2021: A List of Lists

From Five Books:

2021 is the 6th year we’re approaching experts and asking them to recommend the best books published in their field, whether it’s history or historical fiction, science or science fiction, math or memoir, politics or philosophy.

2021 is the 6th year we’re approaching experts and asking them to recommend the best books published in their field, whether it’s history or historical fiction, science or science fiction, math or memoir, politics or philosophy.

Below you’ll find all our interviews on the best books of 2021 as they are published on Five Books. (Our best books of 2020, 2019 and 2018 are also still available: those books are still well worth reading!).

Almost all the book recommendations are based on an individual expert’s choices. In some lists one of our editors makes a selection, based on the vast quantities of books we read every week.

More here.

Santa Barbara

Diana Markosian in Lensculture:

The family has been an infinite well of inspiration for photographers for as long as the medium has existed. From Larry Sultan’s Pictures From Home to LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family, the family unit has proved a conduit for explorations of belonging, identity, strife, place, connection, injustice and more. Photographers have both worked behind the camera and stepped into the frame in order to capture the most universal of subjects, the complications and connections to those we love.

The family has been an infinite well of inspiration for photographers for as long as the medium has existed. From Larry Sultan’s Pictures From Home to LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family, the family unit has proved a conduit for explorations of belonging, identity, strife, place, connection, injustice and more. Photographers have both worked behind the camera and stepped into the frame in order to capture the most universal of subjects, the complications and connections to those we love.

In Diana Markosian’s series Santa Barbara, a story that at first blush feels almost pulled from a movie, family—and the difficult, sometimes incomprehensible decisions made for it—are put on full display. In photographs and a film, the project deals with her family’s journey from post-Soviet Russia to America. In 1996 Markosian’s mother Svetlana, inspired by the American soap opera Santa Barbara that her family watched in Russia, placed an ad in search of a man who could help her and her children immigrate to the US. Awoken in the middle of the night, the children were informed they were going on a trip. The next day they arrived in California and their new American lives began. Markosian, in relating the story, notes how surreal this experience was to her and her family.

More here.

Why Do Women Still Make Less Than Men?

From Harvard Magazine:

Claudia Goldin, Henry Lee professor of economics, shares the reason why working mothers still earn less and advance less often in their careers than men: time. Even with antidiscrimination laws and unbiased managers, certain professions pay employees disproportionately more for long hours and weekends, passing over women who need that time for family care. Goldin also discusses how COVID-19’s flexible work policies may help close the gender earnings gap.

Claudia Goldin, Henry Lee professor of economics, shares the reason why working mothers still earn less and advance less often in their careers than men: time. Even with antidiscrimination laws and unbiased managers, certain professions pay employees disproportionately more for long hours and weekends, passing over women who need that time for family care. Goldin also discusses how COVID-19’s flexible work policies may help close the gender earnings gap.

A transcript from the interview (the following was prepared by a machine algorithm, and may not perfectly reflect the audio file of the interview):

Nancy Kathryn Walecki: Why now when more women graduate college than men and about 30% of working women are mothers, is it still so hard for women to advance their careers and build their families? Why are women still making 81 cents to a man’s dollar as the statistic goes? One reason for the persistent inequality might just be something we all have, but want more of: time. Welcome to the Harvard Magazine podcast, “Ask a Harvard Professor.” I’m Nancy Kathryn Walecki. Joining us for office hours today is Dr. Claudia Goldin, Henry Lee professor of economics, and the first tenured woman in Harvard’s economics department. She’s known for her work on the female labor force and income inequality, and has served as the president of the American Economic Association, and as Director of the Development of the American Economy Program at the National Bureau of Economic Research. Her new book, Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey Toward Equity, looks at the lives of five generations of college-educated women to answer why true workplace equity for working mothers is still out of reach. Welcome, Dr. Goldin.

Claudia Goldin: I’m very glad to be here. And I am Claudia.

More here.

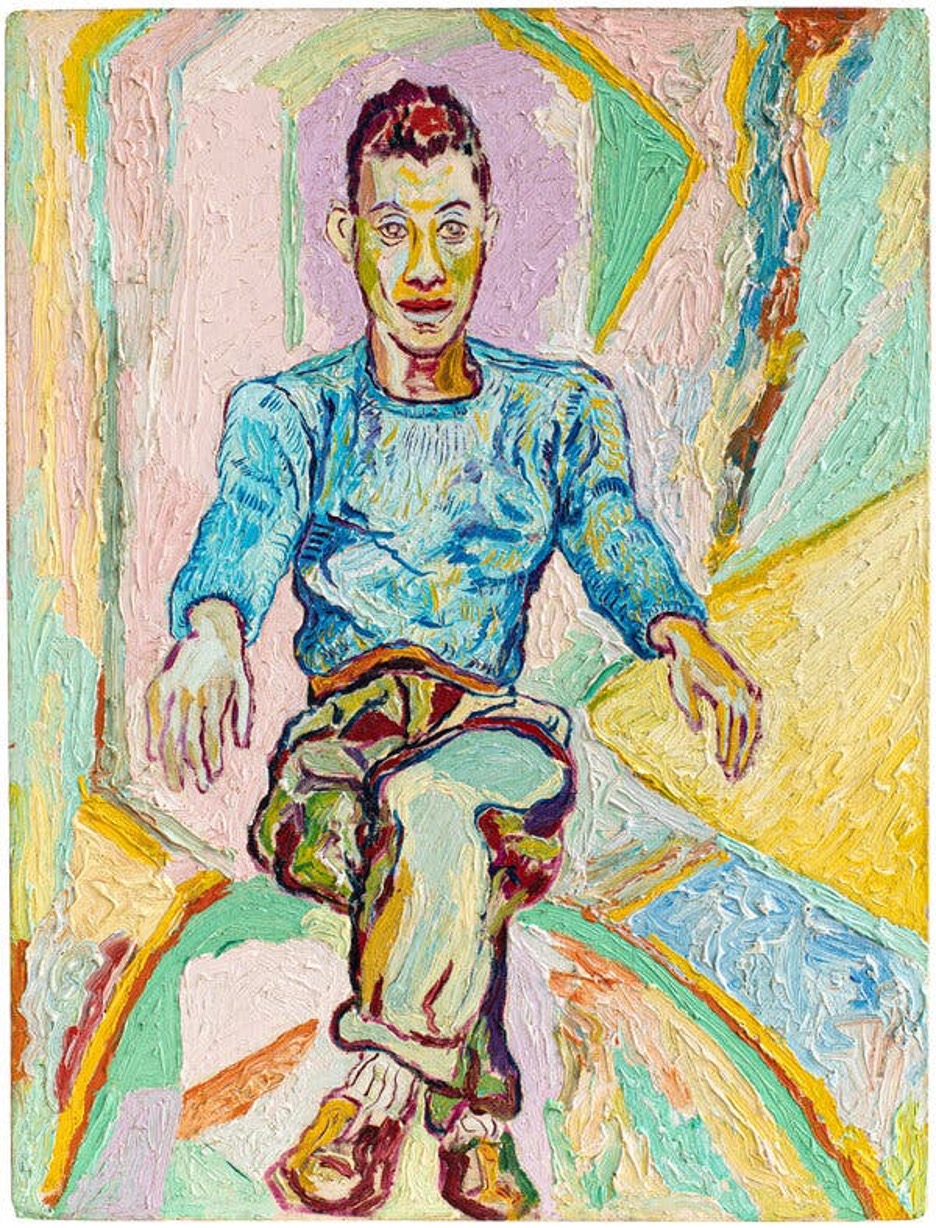

Beauford Delaney. James Baldwin (Circa 1945-50).

Beauford Delaney. James Baldwin (Circa 1945-50).