Month: December 2021

Call Us What We Carry – symphony of hope and solidarity

Kit Fan in The Guardian:

What happens when words spoken on Capitol Hill make us shiver? Amanda Gorman’s luminous poem The Hill We Climb was addressed to Joe Biden and “the world”. Inaugural poems are a fiendishly difficult genre, attempted only six times since JF Kennedy’s ceremony. However, such “occasional” poems play an important cultural role, especially in our time when no public rhetoric and few common values can be taken for granted, as the poet addresses and repairs the damaged foundations of the state itself.

What happens when words spoken on Capitol Hill make us shiver? Amanda Gorman’s luminous poem The Hill We Climb was addressed to Joe Biden and “the world”. Inaugural poems are a fiendishly difficult genre, attempted only six times since JF Kennedy’s ceremony. However, such “occasional” poems play an important cultural role, especially in our time when no public rhetoric and few common values can be taken for granted, as the poet addresses and repairs the damaged foundations of the state itself.

A soaring sense of history and solidarity pervades Gorman’s debut collection. Part elegy, part documentary record, and part witness statement, Call Us What We Carry is first and foremost “a letter to the world”, a phrase she borrows from Emily Dickinson. Like Dickinson’s, Gorman’s poetry puts immense pressure on our present moment, committing itself to an archaeology of our past and conservation of our future. It urges us to revisit the chequered history of intersectional injustices and re-evaluate our fragile species, systems and planet, engulfed by the pandemic, personal grief and public grievances.

“What happened to us”, Gorman writes, “Happened through us.” One of the most haunting things about her book is its retreat from the first-person singular. “I” exists sparingly, peripherally. By contrast, the all-inclusive trio “we”, “us” and “our” occur more than 1,500 times in her shape-shifting poems, a rare feat in the age of overwhelming selfhood. Gorman’s affirmative choric we echoes Martin Luther King’s memorial dream and John Lennon’s utopian lyricism, but her music also draws on the new dimension opened up by trailblazing poets such as Elizabeth Alexander, Anne Carson and Tracy K Smith. She challenges Walt Whitman’s “I am large. I contain multitudes.” In her book, it is we who contain multitudes, and a shared vision, grief and responsibility, as she affirms that “This book is awake. / This book is a wake. / For what is a record but a reckoning?”

More here.

What future science will we invent by 2030?

Jenna Daroczy in CSIROscope:

Our science delivers a lot of exciting breakthroughs to make life better today. But we’re also busy working behind-the-scenes on science that takes a bit longer to develop. Science that will significantly change what the future looks like. We call these areas of cutting-edge research our Future Science Platforms (FSPs). This is because they will be the foundations of tomorrow’s breakthroughs. We kicked off five new FSPs during 2021. We call these areas of cutting-edge research our Future Science Platforms (FSPs). This is because they will be the foundations of tomorrow’s breakthroughs. We kicked off five new FSPs during 2021.

Our science delivers a lot of exciting breakthroughs to make life better today. But we’re also busy working behind-the-scenes on science that takes a bit longer to develop. Science that will significantly change what the future looks like. We call these areas of cutting-edge research our Future Science Platforms (FSPs). This is because they will be the foundations of tomorrow’s breakthroughs. We kicked off five new FSPs during 2021. We call these areas of cutting-edge research our Future Science Platforms (FSPs). This is because they will be the foundations of tomorrow’s breakthroughs. We kicked off five new FSPs during 2021.

…Dr Alan Richardson is the Chief Research Scientist in our Microbiomes for One System Health program. This team will develop our capabilities across agriculture, land-use and human health. “Microorganisms hold huge potential because they are integral in the makeup of all plants and animals. And they are the key drivers of biological and environmental processes,” Alan said. “Our approach will reflect the interconnectivity of microbiomes across systems. It will identify new opportunities to manage the environment, transform food production, waste management, and plant, animal and human health.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Teaching Poetry In A Men’s High Security Prison

I was searched at every edge. I wanted everyone, including me, to be innocent. One inmate squeezed my hand like a letter he’d been hoping for. In the workshop, he read his poem. I applauded. He hugged me. He smelt of stale soap. Leaning in, his stubble sandpapered my softer jaw. He tells me what he did.

He was drunk the night he blacked out, opened his eyes in the kitchen, his wife who wanted divorce, on the floor, dead. I see his wedding ring. I wish I knew her name so I could plant it here.

The next week, the poetry showcase is almost cancelled which causes the inmates to riot. The inmates won. I arrived at the prison for the last time. Flowers placed on all the tables. An inmate read, held himself like his mother’s favorite plant pot. After his poem, everyone applauded, even the guards. The tattooed fists of all those muscular men reached for flowers.

Thrown at men’s feet,

Anaconda red tulips,

Jewels of blood.

Ak Dan Gwang Chil (ADG7)

The Manson Family

Rachel Monroe at The Believer:

One year earlier, in the first throes of my renewed interest in the Manson Family, I had taken the Helter Skelter bus tour operated by Dearly Departed, an outfit specializing in Los Angeles death and murder sites. It sells out nearly every weekend, which is surprising given that there’s actually not much to see anymore. Scott Michaels, Dearly Departed’s founder and main guide, set the tone with a custom soundtrack of hits from 1969 (“In the Year 2525,” “Hair”), cozy oldies made newly spooky by our proximity to death. He also included extensive multimedia add-ons, such as cleavage-heavy clips from Sharon Tate’s early films and Jay Sebring’s cameo on the old bang-pow Batman TV show. Going on the tour is a little like taking a road trip through the parking lots and strip malls of central Los Angeles, accompanied by a group of strangers wearing various skull accessories. Many of the sites aren’t visible or no longer exist. The former Tate-Polanski house on Cielo Drive has been demolished; the site of Rosemary and Leno LaBianca’s murders in Los Feliz is mostly hidden by a hedge.

One year earlier, in the first throes of my renewed interest in the Manson Family, I had taken the Helter Skelter bus tour operated by Dearly Departed, an outfit specializing in Los Angeles death and murder sites. It sells out nearly every weekend, which is surprising given that there’s actually not much to see anymore. Scott Michaels, Dearly Departed’s founder and main guide, set the tone with a custom soundtrack of hits from 1969 (“In the Year 2525,” “Hair”), cozy oldies made newly spooky by our proximity to death. He also included extensive multimedia add-ons, such as cleavage-heavy clips from Sharon Tate’s early films and Jay Sebring’s cameo on the old bang-pow Batman TV show. Going on the tour is a little like taking a road trip through the parking lots and strip malls of central Los Angeles, accompanied by a group of strangers wearing various skull accessories. Many of the sites aren’t visible or no longer exist. The former Tate-Polanski house on Cielo Drive has been demolished; the site of Rosemary and Leno LaBianca’s murders in Los Feliz is mostly hidden by a hedge.

more here.

The Lighted Window: Evening Walks Remembered

Seamus Perry at Literary Review:

Davidson is evidently a great wanderer and his book, largely an account of his nocturnal wanderings and the thoughts inspired by them, is itself an engagingly wandering affair. It is a work of great charm, moving from text to text and painting to painting in a disarmingly associative way: the connective tissue of the work is a network of phrases such as ‘My mind circles back…’, ‘I think of other lights which shine in more than one dimension…’, ‘I am reminded of an odd fragment of narrative…’ and ‘My thoughts moved to a far comparison…’. We begin and end accompanying the author through the crepuscular autumnal fog beside the Thames in Oxford, and in between we follow him through the sighing willows of Ghent, the frozen mid-afternoon darkness of Stockholm, the scruffy urban romance of central London, the smart neoclassical streets of Edinburgh’s New Town, the autumnal fields of Norfolk and the snows of Princeton. And as we make our way, Davidson tells us what emerges from his extraordinarily well-stocked mind.

Davidson is evidently a great wanderer and his book, largely an account of his nocturnal wanderings and the thoughts inspired by them, is itself an engagingly wandering affair. It is a work of great charm, moving from text to text and painting to painting in a disarmingly associative way: the connective tissue of the work is a network of phrases such as ‘My mind circles back…’, ‘I think of other lights which shine in more than one dimension…’, ‘I am reminded of an odd fragment of narrative…’ and ‘My thoughts moved to a far comparison…’. We begin and end accompanying the author through the crepuscular autumnal fog beside the Thames in Oxford, and in between we follow him through the sighing willows of Ghent, the frozen mid-afternoon darkness of Stockholm, the scruffy urban romance of central London, the smart neoclassical streets of Edinburgh’s New Town, the autumnal fields of Norfolk and the snows of Princeton. And as we make our way, Davidson tells us what emerges from his extraordinarily well-stocked mind.

more here.

A new book about the Boeing 737 MAX disaster

Maureen Tkacik in The American Prospect:

Boeing’s self-hijacking plane took its first 189 lives on October 29, 2018, just over two months after it had been delivered to the Jakarta Airport terminal of Indonesia’s reigning discount carrier Lion Air. Fishermen described the fuselage plunging nose-first, directly perpendicular to the Java Sea, at speeds many times that of Komarov’s four-and-a-half mile descent from the half-baked Soyuz 1, with its malfunctioning parachutes. A 48-year-old diver dispatched to plumb the deep sea floor for body parts and the elusive cockpit voice recorder became the 190th fatality. As with the Soyuz, in which the famous cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was said to have detailed 200 outstanding manufacturing defects in a memo to superiors, the 737 MAX had been the subject of numerous ignored whistleblower reports, tormented confessions, and abrupt career changes; the general manager of the plane’s final assembly line outside Seattle had resigned in despair the week Lion Air took delivery.

Boeing’s self-hijacking plane took its first 189 lives on October 29, 2018, just over two months after it had been delivered to the Jakarta Airport terminal of Indonesia’s reigning discount carrier Lion Air. Fishermen described the fuselage plunging nose-first, directly perpendicular to the Java Sea, at speeds many times that of Komarov’s four-and-a-half mile descent from the half-baked Soyuz 1, with its malfunctioning parachutes. A 48-year-old diver dispatched to plumb the deep sea floor for body parts and the elusive cockpit voice recorder became the 190th fatality. As with the Soyuz, in which the famous cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was said to have detailed 200 outstanding manufacturing defects in a memo to superiors, the 737 MAX had been the subject of numerous ignored whistleblower reports, tormented confessions, and abrupt career changes; the general manager of the plane’s final assembly line outside Seattle had resigned in despair the week Lion Air took delivery.

But three years later, nothing has surfaced to suggest that any senior official at Boeing took so much as a passing glance at the corpse stew its greed chucked into the Java Sea, much less any semblance of responsibility.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Joshua Greene on Morality, Psychology, and Trolley Problems

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

We all know you can’t derive “ought” from “is.” But it’s equally clear that “is” — how the world actual works — is going to matter for “ought” — our moral choices in the world. And an important part of “is” is who we are as human beings. As products of a messy evolutionary history, we all have moral intuitions. What parts of the brain light up when we’re being consequentialist, or when we’re following rules? What is the relationship, if any, between those intuitions and a good moral philosophy? Joshua Greene is both a philosopher and a psychologist who studies what our intuitions are, and uses that to help illuminate what morality should be. He gives one of the best defenses of utilitarianism I’ve heard.

We all know you can’t derive “ought” from “is.” But it’s equally clear that “is” — how the world actual works — is going to matter for “ought” — our moral choices in the world. And an important part of “is” is who we are as human beings. As products of a messy evolutionary history, we all have moral intuitions. What parts of the brain light up when we’re being consequentialist, or when we’re following rules? What is the relationship, if any, between those intuitions and a good moral philosophy? Joshua Greene is both a philosopher and a psychologist who studies what our intuitions are, and uses that to help illuminate what morality should be. He gives one of the best defenses of utilitarianism I’ve heard.

More here.

Time to Overhaul the Global Financial System

Jeffrey D. Sachs in Project Syndicate:

At last month’s COP26 climate summit, hundreds of financial institutions declared that they would put trillions of dollars to work to finance solutions to climate change. Yet a major barrier stands in the way: The world’s financial system actually impedes the flow of finance to developing countries, creating a financial death trap for many.

At last month’s COP26 climate summit, hundreds of financial institutions declared that they would put trillions of dollars to work to finance solutions to climate change. Yet a major barrier stands in the way: The world’s financial system actually impedes the flow of finance to developing countries, creating a financial death trap for many.

Economic development depends on investments in three main kinds of capital: human capital (health and education), infrastructure (power, digital, transport, and urban), and businesses. Poorer countries have lower levels per person of each kind of capital, and therefore also have the potential to grow rapidly by investing in a balanced way across them. These days, that growth can and should be green and digital, avoiding the high-pollution growth of the past.

Global bond markets and banking systems should provide sufficient funds for the high-growth “catch-up” phase of sustainable development, yet this doesn’t happen. The flow of funds from global bond markets and banks to developing countries remains small, costly to the borrowers, and unstable. Developing-country borrowers pay interest charges that are often 5-10% higher per year than the borrowing costs paid by rich countries.

Developing country borrowers as a group are regarded as high risk. The bond rating agencies assign lower ratings by mechanical formula to countries just because they are poor. Yet these perceived high risks are exaggerated, and often become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

More here.

Stephen Sondheim had an interesting discussion with Steven Pinker in 2016

Tuesday Poem

One Art

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

The big idea: how much do we really want to know about our genes?

Daniel Davis in The Guardian:

While at the till in a clothes shop, Ruby received a call. She recognised the woman’s voice as the genetic counsellor she had recently seen, and asked if she could try again in five minutes. Ruby paid for her clothes, went to her car, and waited alone. Something about the counsellor’s voice gave away what was coming. The woman called back and said Ruby’s genetic test results had come in. She did indeed carry the mutation they had been looking for. Ruby had inherited a faulty gene from her father, the one that had caused his death aged 36 from a connective tissue disorder that affected his heart. It didn’t seem the right situation in which to receive such news but, then again, how else could it happen? The phone call lasted just a few minutes. The counsellor asked if Ruby had any questions, but she couldn’t think of anything. She rang off, called her husband and cried. The main thing she was upset about was the thought of her children being at risk.

While at the till in a clothes shop, Ruby received a call. She recognised the woman’s voice as the genetic counsellor she had recently seen, and asked if she could try again in five minutes. Ruby paid for her clothes, went to her car, and waited alone. Something about the counsellor’s voice gave away what was coming. The woman called back and said Ruby’s genetic test results had come in. She did indeed carry the mutation they had been looking for. Ruby had inherited a faulty gene from her father, the one that had caused his death aged 36 from a connective tissue disorder that affected his heart. It didn’t seem the right situation in which to receive such news but, then again, how else could it happen? The phone call lasted just a few minutes. The counsellor asked if Ruby had any questions, but she couldn’t think of anything. She rang off, called her husband and cried. The main thing she was upset about was the thought of her children being at risk.

Over the next few weeks, she Googled, read journal articles, and tried to become an expert patient in what was quite a rare genetic disorder. There wasn’t much to go on, and, not being a scientist herself, it was hard for her to evaluate what she did find. She learned that a link between mutations in this particular gene and connective tissue problems had only recently been discovered. A few years earlier this disease did not exist, or at least it had yet to be named. Over time, some details emerged. Nobody had ever seen her own family’s particular mutation in anyone else. So that meant it was very hard to know what to make of her situation. Her risk of a heart problem was surely increased, but nobody could say by how much.

More here.

Are My Stomach Problems Really All in My Head?

Constance Sommer in The New York Times:

The New Mexican desert unrolled on either side of the highway like a canvas spangled at intervals by the smallest of towns. I was on a road trip with my 20-year-old son from our home in Los Angeles to his college in Michigan. Eli, trying to be patient, plowed down I-40 as daylight dimmed and I scrolled through my phone searching for a restaurant or dish that would not cause me pain. After years of carefully navigating dinners out and meals in, it had finally happened: There was nowhere I could eat.

The New Mexican desert unrolled on either side of the highway like a canvas spangled at intervals by the smallest of towns. I was on a road trip with my 20-year-old son from our home in Los Angeles to his college in Michigan. Eli, trying to be patient, plowed down I-40 as daylight dimmed and I scrolled through my phone searching for a restaurant or dish that would not cause me pain. After years of carefully navigating dinners out and meals in, it had finally happened: There was nowhere I could eat.

“I’m so sorry, honey,” I said. “I feel really, really bad.” And I did. I was on the verge of tears, as much out of self-pity and shame as any maternal concern. Eli shook his head. “It’s OK, Mom. It’s not your fault.” But it was. Because of me — or, to be precise, my digestive system — we would not eat until we reached Amarillo, Texas, at 10 p.m., and bought frozen food from a grocery store near our Airbnb. My gut is not a carefree traveler. Ingest the wrong items, and my stomach feels as though someone’s scoured it with a Brillo pad. For the next few hours, I may also experience migraines, achy joints and a foggy, feverish sensation like I’m coming down with the flu. My doctors call this irritable bowel syndrome, or I.B.S. I call it a terrible shame.

More here.

The Demands of Citizenship: JFK at Vanderbilt

But this Nation was not founded solely on the principle of citizens’ rights. Equally important, though too often not discussed, is the citizen’s responsibility. For our privileges can be no greater than our obligations. —John F. Kennedy, May 18, 1963, Nashville

May, 1963. JFK is in a centrifuge, buffeted by a series of challenges from abroad and at home that would have taxed anyone. Underneath the glamour and optimism of Camelot was a roiling mess of seemingly intractable problems, including the global threat of an aggressive, expansive Communism, and domestic unrest related to the irrefutable moral logic of the Civil Rights Movement set against implacable, and often violent, resistance.

All of this, the triumphs and the troubles, are, for the first time, playing out in black and white (and occasionally in living color) on television screens across America. We have clearly moved into a “see it now” age: in just the decade of the 1950s, the percentage of households with sets went from about 9% to about 87%. Soft censorship (reporter circumspection and editorial oversight) still existed, but the vast majority of people were getting their news visually, and sometimes that news contained graphic and unforgettable images.

Kennedy clearly understood the power of the new medium. He wrote a short essay for TV Guide in November 1959, in which he discussed his concerns about television’s potential for demagoguery, but also said it gave an opportunity to the viewing public to judge for itself a candidate’s sincerity—or lack of it. If that was a prediction, it was a pretty good one: Ten months later, in what was a decisive moment in the 1960 election, he was debating Richard Nixon, and winning, in part, on style points. Read more »

What A Way To Go

by Usha Alexander

[This is the fifteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

I began writing this series eighteen months ago to explore the human experience and human potential in the face of climate change, through the stories we tell. It’s been a remarkable journey for me as I followed trails of questions through new fields of ideas along entirely unexpected paths of enquiry. New vistas revealed themselves, sometimes perilous, always compelling. And so I went. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve come to realize that our present environmental predicament is actually far worse off—that is to say, more threatening to near-term human wellbeing and civilizational integrity—than most of us recognize. This journey is changing me. So when I now look at contemporary works of fiction about climate change—so-called cli-fi, which I’d hoped might provide fresh insights—so much of it strikes me as somewhat underwhelming before the task: narrow, shallow, tepid, unimaginative, or even dishonest.

I began writing this series eighteen months ago to explore the human experience and human potential in the face of climate change, through the stories we tell. It’s been a remarkable journey for me as I followed trails of questions through new fields of ideas along entirely unexpected paths of enquiry. New vistas revealed themselves, sometimes perilous, always compelling. And so I went. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve come to realize that our present environmental predicament is actually far worse off—that is to say, more threatening to near-term human wellbeing and civilizational integrity—than most of us recognize. This journey is changing me. So when I now look at contemporary works of fiction about climate change—so-called cli-fi, which I’d hoped might provide fresh insights—so much of it strikes me as somewhat underwhelming before the task: narrow, shallow, tepid, unimaginative, or even dishonest.

At the same time, a few conclusions have begun to coalesce in my mind. Some of these may seem controversial, largely because they run contrary to the common narratives that anchor our dominant understanding of how the world works—our stories of human exceptionalism, technological magic, and the tenets of capitalist faith. Indeed, many of my own assumptions and worldviews have been challenged, altered, or broken. In their stead, new ways of thinking have taken root, as I began seeing through at least some of our most cherished cultural fabrications to understand our quandary with a different perspective.

Learning these things has been emotionally taxing, but I don’t believe there’s any way forward without a clear-eyed, big-picture view of our planetary and civilizational plight. And so, for better or worse, I wish to sum up my thoughts here, before ending my explorations through this series, which I next expect to turn toward thoughts on how one might respond to it all: hope, despair, expectation, fear, carrying on, looking ahead, finding new stories. I trust there are others out there, who would also rather reckon with what’s happening than go on pretending we needn’t adjust our expectations for the future… although, I confess, there are certainly days when I envy those who are able to go on pretending. What follows isn’t for the faint of heart: Read more »

Monday Poem

A Question of Necessity

“Can you tell me a certain thing

that is a moral fact?” is a

specious question

because the fact of the thing

exists as something essential

to the survival of homo sapiens

in creating civilization, though civilization

does not always live up to the necessity

of its essential thing.(the root

of what it means to be civilized) so the fact

of chaos, or free natural inclination,

becomes the universal mode simply because

morality, being thought subjective, and a

hard taskmaster, cannot be universally defined

and we all become hawks or vultures

feeding on carrion doves. it’s a question

whose answer itself is not an easy act

but is, nevertheless, with or without definition, love,

which is foremost not a thing we feel, but … do:

………………………………………………………………a moral act

…………………………………………………………….. made fact

Jim Culleny

9/13/20

Where shall wisdom be found?

by Jeroen Bouterse

Permanent Crisis

In one of the opening scenes of The Chair (2021), we are treated to an ideal-typical self-diagnosis of a struggling English department. Its new chair, Ji-Yoon Kim, narrates:

I’m not gonna sugarcoat this: we are in dire crisis. Enrollments are down more than 30 percent, our budget is being gutted. It feels like the sea is washing the ground out from under our feet. But in these unprecedented times, we have to prove that what we do in the classroom – modeling critical thinking, stressing the value of empathy – is more important than ever, and has value to the public good. It’s true, we can’t teach our students coding or engineering. What we teach them cannot be quantified, or put down on a resumé as a skill. But let us have pride in what we can offer future generations. We need to remind these young people that knowledge doesn’t just come from spreadsheets or Wiki entries. Hey, I was thinking this morning about our tech-addled culture and how our students are hyperconnected 24 hours a day, and I was reminded of something Harold Bloom wrote. He said: ‘Information is endlessly available to us. Where shall wisdom be found?’

The idea that a humanities department would be experiencing rough times is not a hard sell. The series uses the high-mindedness of this speech to let the silly and petty behavior of the faculty stand out more, but it also leaves little question that Ji-Yoon’s diagnosis is basically right: it is simultaneously extremely hard to defend the value of the humanities in this day and age, and especially important, because they offer something that runs counter to what we tend to believe the tendencies of that day and age to be – instrumentalism, materialism, marketability, et cetera.

Precisely what that value consists of is contested, and generic crisis talk is also a way for the chair not to become too specific – in particular, not to choose sides between the older, canon-oriented generation (the men in the scene nod in relief when Ji-Yoon name-drops Harold Bloom) and the younger, progressive staff. The main point now, however, is that this diagnosis is immediately recognizable: while there are skills that fit comfortably within the modern economy, Ji-Yoon says, the humanities are untimely; they provide a kind of knowledge that our society both needs and undervalues. Read more »

Keeping House

by Michael Abraham-Fiallos

I am a messy person.

I am a messy person, and I don’t like to clean. My house testifies to this: cups in the sink, mail on the counter, books spilling off the windowsills, too much laundry in the bin, a scattering of incense dust on the coffee table alongside burnt out candles and ephemera (an old insurance card, jewelry, more books). About twice a month, I get fed up with myself and obsessively clean the house. Or company comes, and I scramble. But the rest of the time, I subsist in my mess. My psychiatrist thinks this is a matter of motivation, of the depressive side of manic depression. It is less that and more a matter of being a wanderer somewhere else, in a place wet with rain and glistening with wildflowers, in a place where the wind is always whistling, and the sun hangs perpetually low to the horizon, casting its light yellow and fragile past the hills and across the valley. This place is a place in my own head, a space where the eros in me dwells, where my capacity to bring things forth into the world exists, where the grand feelings and the big thoughts are. In the lull of the afternoon, I find myself at my keyboard exploring myself, and I forget to run the washing machine. Or, I take long walks in the daylight to get mired in thought, and the dishes be damned. When my husband arrives home from work, there is so much to tell him, so much to show him, which has been found or made or thought up—which has been brought forth—in the wandering, so much to hear from him that might provoke tomorrow’s wandering (all my best wandering has something to do with my husband).

Maybe what I mean is I’m lazy or perhaps distracted. It’s a cliché about scholars and writers (skola does, after all, mean “leisure”): so wrapped up in their minds that the external world around them fades into the background. In the matter of keeping house, I fit this cliché. However, there is more to keeping house than tidiness.

I have always thought it was a funny phrase: keeping house. What is one keeping? It seems to me that one is keeping something alive, keeping something kindled, as one does a flame with one’s hand. Something precious and vibrant is meant to be kept at the center of the home, as once, not so long ago, the hearth was kept stoked to keep the home warm and habitable. Upon thinking this, I went searching for what this something might be that one keeps alive or open or warm with one’s care and attention, went searching for what it is that makes a house a house. I found the answer, as I always seem to do, in the concept of love, but in a very peculiar and striking account of what love is: what the French feminist philosopher, Luce Irigaray, calls demonic love or sorcerer love. She explicates this concept in an essay titled “L’amour Sorcier: Lecture de Platon, Le Banquet, Discours de Diotime,” rendered in English by Eleanor H. Kuykendall as “Sorcerer Love: A reading of Plato’s Symposium, Diotima’s Speech.” It appears in a volume titled Luce Irigaray in French in 1984, and Kuykendall published her translation in 1989. Read more »

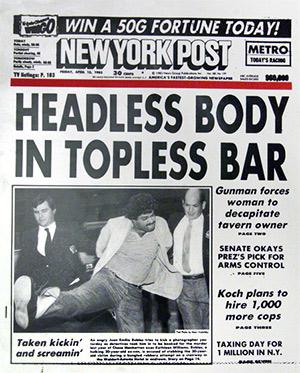

Why Today’s Republicans Hate the New York Times So Much

by Akim Reinhardt

When I was growing up during the 1970s, America still had a vibrant and thriving newspaper culture. My hometown New York City boasted a half-dozen dailies to choose from, plus countless neighborhood newspapers. Me and other kids started reading newspapers in about the 5th grade. Sports sections, comics, and movie listings mostly, but still. By middle school, newspapers were all over the place, and not because teachers foisted them upon us, but because kids picked them up on the way to school and read them.

When I was growing up during the 1970s, America still had a vibrant and thriving newspaper culture. My hometown New York City boasted a half-dozen dailies to choose from, plus countless neighborhood newspapers. Me and other kids started reading newspapers in about the 5th grade. Sports sections, comics, and movie listings mostly, but still. By middle school, newspapers were all over the place, and not because teachers foisted them upon us, but because kids picked them up on the way to school and read them.

Of course when dropping coins at the local newsstands and into boxes, us youngsters typically picked up tabloids such as the New York Post and Daily News, not those fancy papers so big you had to unfold them just to see the entire front page: the New York Times and the indecipherable Wall Street Journal. Those were for adults, and usually white collar ones at that.

My father was blue collar and not a big newspaper reader. But my mother was a high school English teacher and she made a family ritual of going out to buy the massive Sunday Times when it first hit newsstands on Saturday evenings. Mostly she just wanted the Book Review. We’d also pick up a Daily News because they too had a formidable Sunday edition; not cut into sections like the Times, but in a single massive tome like a phonebook. It had the best comics section of any NYC paper. After my sister and I had our way with the News, I’d occasionally thumb through the Times. No comics, but they did have an entire sports section.

As I rambled towards adulthood, I continued buying the tabloids for their local sports coverage and hilarious front page headlines. However, I also found myself reading more of that Sunday Times. Never all of it, of course. I was far too young, and anyway, never trust anyone who does; no one’s interests are really that far ranging. Read more »