Brandon Kiem in Nautilus:

In the annals of transportation history persists a tale of how automobiles in the early 20th century helped cities conquer their waste problems. It’s a tidy story, so to speak, about dirty horses and clean cars and technological innovation. As typically told, it’s a lesson we can learn from today, now that cars are their own environmental disaster, and one that technology can no doubt solve. The story makes perfect sense to modern ears and noses: After all, Americans love their cars! And who’d want to walk through ankle-deep horse manure to buy a newspaper? There’s just one problem with the story. It’s wrong.

In the annals of transportation history persists a tale of how automobiles in the early 20th century helped cities conquer their waste problems. It’s a tidy story, so to speak, about dirty horses and clean cars and technological innovation. As typically told, it’s a lesson we can learn from today, now that cars are their own environmental disaster, and one that technology can no doubt solve. The story makes perfect sense to modern ears and noses: After all, Americans love their cars! And who’d want to walk through ankle-deep horse manure to buy a newspaper? There’s just one problem with the story. It’s wrong.

For a recent telling, you can turn to SuperFreakonomics, the best-selling 2009 book by economist Steven D. Levitt and journalist Stephen J. Dubner. The authors describe how, in the late 19th century, the streets of fast-industrializing cities were congested with horses, each pulling a cart or a coach, one after the other, in some places three abreast. There were something like 200,000 horses in New York City alone, depositing manure at a rate of roughly 35 pounds per day, per horse. It piled high in vacant lots and “lined city streets like banks of snow.” The elegant brownstone stoops so beloved of contemporary city-dwellers allowed homeowners to “rise above a sea of manure.” In Rochester, N. Y., health officials calculated that the city’s annual horse waste would, if collected on a single acre, make a 175-foot-tall tower.

“The world had seemingly reached the point where its largest cities could not survive without the horse but couldn’t survive with it, either,” write Levitt and Dubner. A main solution, as they portray it, came in the form of cars, which, compared to horses, were a godsend, their adoption inevitable. “The automobile, cheaper to own and operate than a horse-drawn vehicle was proclaimed an ‘environmental savior.’ Cities around the world were able to take a deep breath—without holding their noses at last—and resume their march of progress.” To Levitt and Dubner, this historical turnabout teaches that technological innovation solves problems, and if it creates new problems, innovation will solve those, too.

It’s far too simplistic an interpretation. Cars didn’t replace horses, at least not in the way we usually think, and it was social as much as technological progress that solved the era’s pollution problems. As we confront our current car troubles—particulate and greenhouse gas pollutions, accidents and deaths, wasteful swaths of the landscape dedicated to automobiles—these are lessons we’d do well to recall.

More here.

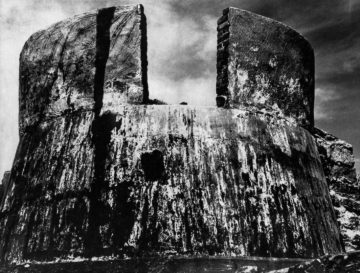

EARLY IN JULY 1958, the Japanese photographer Kikuji Kawada, then aged twenty-five and a staffer at the weekly magazine Shukan Shincho, visited Hiroshima for a cover story to run in the month following. He was there to photograph another photographer, Ken Domon, whose book Hiroshima had been published in the spring. Among Domon’s subjects: the scarred bodies of survivors of the atomic-bomb attack of August 6, 1945, and the skeletal dome of the city’s riverside industrial exhibition hall. When he had finished his assignment, Kawada lingered in the ruins below the Genbaku Dome, where brick and concrete walls were covered with stains composing, as he put it, “an audibly violent whirlpool.” Kawada took no photographs of the enigmatic markings, but returned two years later with a 4 x 5 view camera, and began making long exposures in “this terrifying, unknown place.”

EARLY IN JULY 1958, the Japanese photographer Kikuji Kawada, then aged twenty-five and a staffer at the weekly magazine Shukan Shincho, visited Hiroshima for a cover story to run in the month following. He was there to photograph another photographer, Ken Domon, whose book Hiroshima had been published in the spring. Among Domon’s subjects: the scarred bodies of survivors of the atomic-bomb attack of August 6, 1945, and the skeletal dome of the city’s riverside industrial exhibition hall. When he had finished his assignment, Kawada lingered in the ruins below the Genbaku Dome, where brick and concrete walls were covered with stains composing, as he put it, “an audibly violent whirlpool.” Kawada took no photographs of the enigmatic markings, but returned two years later with a 4 x 5 view camera, and began making long exposures in “this terrifying, unknown place.”

T

T It was a Monday morning, which was reason enough to meditate. I was anxious about the day ahead, and so, as I’ve done countless times over the past few years, I settled in on my couch for a short meditation session. But something was different this morning.

It was a Monday morning, which was reason enough to meditate. I was anxious about the day ahead, and so, as I’ve done countless times over the past few years, I settled in on my couch for a short meditation session. But something was different this morning. I have seen many things (corpses, the Northern Lights, a beached whale), but a few sights have left a particularly vivid impression. One is of a boy I spotted in Istanbul eighteen years ago. He was fifteen or so, with a pathetic whispy moustache, wearing a suit for what appeared to be the first time. We were in the textile district of Zeytinburnu, and it seemed to me he was likely beginning a new life in his father’s small business, though I could be wrong. Whatever the occasion, the boy had deemed fitting to commission the labor of an even smaller boy, nine years old or so, to shine his shoes. The shoeshine kid was kneeling on the ground, scrubbing away with rags and polish from his portable kit, a borderline-homeless street gamin for whom all of our rhetoric about the sacred innocence of childhood means nothing at all. The fifteen-year-old stared down haughtily, like a small sovereign, and the nine-year-old, knowing his place, did not dare even to look up.

I have seen many things (corpses, the Northern Lights, a beached whale), but a few sights have left a particularly vivid impression. One is of a boy I spotted in Istanbul eighteen years ago. He was fifteen or so, with a pathetic whispy moustache, wearing a suit for what appeared to be the first time. We were in the textile district of Zeytinburnu, and it seemed to me he was likely beginning a new life in his father’s small business, though I could be wrong. Whatever the occasion, the boy had deemed fitting to commission the labor of an even smaller boy, nine years old or so, to shine his shoes. The shoeshine kid was kneeling on the ground, scrubbing away with rags and polish from his portable kit, a borderline-homeless street gamin for whom all of our rhetoric about the sacred innocence of childhood means nothing at all. The fifteen-year-old stared down haughtily, like a small sovereign, and the nine-year-old, knowing his place, did not dare even to look up. When it comes to climate finance, the gap between what is needed and what is on the table is dizzying. The talk at the conference was all about the annual $100bn (£75bn) that rich countries had promised to poorer nations

When it comes to climate finance, the gap between what is needed and what is on the table is dizzying. The talk at the conference was all about the annual $100bn (£75bn) that rich countries had promised to poorer nations  On Thursday evening, March 28, every seat and open space in Columbia University’s McMillin Theater was taken. Those who still stood in line and hoped for entry were out of luck. The scene was without precedent. No lecture delivered in French at Columbia had ever drawn more than two or three hundred listeners, and yet four or five times that many had come to hear Albert Camus read his prepared remarks entitled “La Crise de l’Homme” (“The Human Crisis”). What they heard was not the cultural excursion they had come for. Instead, it was arguably the most prophetic and unsettling speech Camus ever gave.

On Thursday evening, March 28, every seat and open space in Columbia University’s McMillin Theater was taken. Those who still stood in line and hoped for entry were out of luck. The scene was without precedent. No lecture delivered in French at Columbia had ever drawn more than two or three hundred listeners, and yet four or five times that many had come to hear Albert Camus read his prepared remarks entitled “La Crise de l’Homme” (“The Human Crisis”). What they heard was not the cultural excursion they had come for. Instead, it was arguably the most prophetic and unsettling speech Camus ever gave.

Few historians write better about pictures than Uglow, and her commentaries make you look and look again at bright colour plates that deliver little shocks. Physically, linocuts are not large: the whirligig of Cyril’s The Merry-go-round and the glorious swirl of ’Appy ’Ampstead burst from confined spaces; The Eight and Bringing in the Boat are not much bigger than a sheet of A4. The technical ability required to succeed in this medium is immense. The same could be said for piecing together the lives of individuals who covered their tracks and told themselves stories that were only partially true. Enough scraps survive to suggest that Cyril loved Sybil and was sad to lose her (he went back to his ‘quiet’ and kindly, amenable wife, and nothing was said in the family about his twenty-year absence). Sybil, who settled happily on Vancouver Island and whose reputation grew as she continued to work, was always busy, if not sketching and painting and linocutting then teaching, making her own clothes and boiling prodigious quantities of jam. To her brisk denial that her domestic relationship with her artist-collaborator had been that of lover, Uglow responds, ‘and who can deny her the right to possess the facts of her own life?’

Few historians write better about pictures than Uglow, and her commentaries make you look and look again at bright colour plates that deliver little shocks. Physically, linocuts are not large: the whirligig of Cyril’s The Merry-go-round and the glorious swirl of ’Appy ’Ampstead burst from confined spaces; The Eight and Bringing in the Boat are not much bigger than a sheet of A4. The technical ability required to succeed in this medium is immense. The same could be said for piecing together the lives of individuals who covered their tracks and told themselves stories that were only partially true. Enough scraps survive to suggest that Cyril loved Sybil and was sad to lose her (he went back to his ‘quiet’ and kindly, amenable wife, and nothing was said in the family about his twenty-year absence). Sybil, who settled happily on Vancouver Island and whose reputation grew as she continued to work, was always busy, if not sketching and painting and linocutting then teaching, making her own clothes and boiling prodigious quantities of jam. To her brisk denial that her domestic relationship with her artist-collaborator had been that of lover, Uglow responds, ‘and who can deny her the right to possess the facts of her own life?’ Last May, after the Isla Vista shooter’s manifesto revealed a deep misogyny, women went online to talk about the violent retaliation of men they had rejected, to describe the feeling of being intimidated or harassed. These personal experiences soon took on a sense of universality. And so #yesallwomen was born—yes all women have been victims of male violence in one form or another.

Last May, after the Isla Vista shooter’s manifesto revealed a deep misogyny, women went online to talk about the violent retaliation of men they had rejected, to describe the feeling of being intimidated or harassed. These personal experiences soon took on a sense of universality. And so #yesallwomen was born—yes all women have been victims of male violence in one form or another. In the annals of transportation history persists a tale of how automobiles in the early 20th century helped cities conquer their waste problems. It’s a tidy story, so to speak, about dirty horses and clean cars and technological innovation. As typically told, it’s a lesson we can learn from today, now that cars are their own environmental disaster, and one that technology can no doubt solve. The story makes perfect sense to modern ears and noses: After all, Americans love their cars! And who’d want to walk through ankle-deep horse manure to buy a newspaper? There’s just one problem with the story. It’s wrong.

In the annals of transportation history persists a tale of how automobiles in the early 20th century helped cities conquer their waste problems. It’s a tidy story, so to speak, about dirty horses and clean cars and technological innovation. As typically told, it’s a lesson we can learn from today, now that cars are their own environmental disaster, and one that technology can no doubt solve. The story makes perfect sense to modern ears and noses: After all, Americans love their cars! And who’d want to walk through ankle-deep horse manure to buy a newspaper? There’s just one problem with the story. It’s wrong. What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are.

What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are. Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.