Unto Others

….. To a roomful of people at a private fundraiser for Mitt

….. Romney, Mormon; US presidential candidate, May 2012

….. “There are 47 percent who are with (the President),

….. who are dependent upon government, who believe that

….. they are victims, who believe that government has a

….. responsibility to care for them, who believe that they

….. are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you

….. name it. . . . That’s entitlement.” —Mitt Romney

….. “All things therefore whatsoever ye would that men should

….. do unto you, even so do ye also unto them.” —Matthew 7:12

….. “Who is here so vile that he will not love his country? If any,

….. speak; for him have I offended.” —Julius Caesar, act 3, scene 2

Who there knows how good it is to know

a warm bed and a roof? If any, speak.

Who there knows how good it is to know

a schoolroom? If any, speak.

Who there knows how good it is to know

the stiffness of new shoes? If any, speak.

Who there knows how good it is to know

the steam of a meal on your cheeks? If any, speak.

Who there knows how good it is to know

some God hears you weep? If any, speak.

Who there knows how good it is to know?

All of you know, so speak.

Say you know how good it is to know.

All of you know, so speak. Say it’s OK

for others to know how good it is to know.

Go ahead, speak.

If you know how good it is to know,

why then don’t you speak?

Why then don’t you speak?

Say something. Speak. Speak. Speak.

by Lauren Marie Schmidt

from Filthy Labors

Curbstone Books, 2017

Though the moon was long considered a barren, inhospitable rocky world, researchers over the past few decades have found that the moon has many of the amenities that humans would need to build a self-sufficient habitat. Indeed, recent discoveries of

Though the moon was long considered a barren, inhospitable rocky world, researchers over the past few decades have found that the moon has many of the amenities that humans would need to build a self-sufficient habitat. Indeed, recent discoveries of  When people think of ways to help the world’s poor, a few obvious ideas come to mind:

When people think of ways to help the world’s poor, a few obvious ideas come to mind:  We will meet climate change with real change, and defeat the fossil-fuel industry in the next nine years.

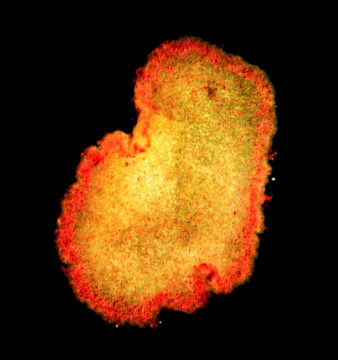

We will meet climate change with real change, and defeat the fossil-fuel industry in the next nine years. In dozens of laboratory freezers at Columbia University in New York City, 60,000 cancer specimens await testing that oncologist Azra Raza, M.D., anticipates will find “cancer’s first cell” — the earliest mutated cell that will eventually multiply to become a cancer — and lead to treatments that knock the disease out before it grows. The blood and bone marrow samples come from nearly every one of her patients of 35 years, provided as they moved through cancer treatment.

In dozens of laboratory freezers at Columbia University in New York City, 60,000 cancer specimens await testing that oncologist Azra Raza, M.D., anticipates will find “cancer’s first cell” — the earliest mutated cell that will eventually multiply to become a cancer — and lead to treatments that knock the disease out before it grows. The blood and bone marrow samples come from nearly every one of her patients of 35 years, provided as they moved through cancer treatment. The carceral system has become a vast debt machine. It creates a dizzying array of financial obligations for those unfortunate enough to be caught in its dragnet. The lowest hanging fruits are the traffic fines extracted from motorists who fall foul of a speed trap, carefully laid by officers assigned to do “

The carceral system has become a vast debt machine. It creates a dizzying array of financial obligations for those unfortunate enough to be caught in its dragnet. The lowest hanging fruits are the traffic fines extracted from motorists who fall foul of a speed trap, carefully laid by officers assigned to do “

CABINET:

CABINET:  B

B The tile floor was cold and hard against my knees, but I couldn’t move from my spot in front of the toilet. It was the third morning that week I had spent violently throwing up because of anxiety at the prospect of going into the lab. So far, I had been able to stay home without consequence. But that day I was scheduled to meet other lab members to work on an experiment essential for my Ph.D. project. At 5:45 a.m. I let them know I wouldn’t be coming in, feeling a wave of guilt. “How did I get here?” I wondered.

The tile floor was cold and hard against my knees, but I couldn’t move from my spot in front of the toilet. It was the third morning that week I had spent violently throwing up because of anxiety at the prospect of going into the lab. So far, I had been able to stay home without consequence. But that day I was scheduled to meet other lab members to work on an experiment essential for my Ph.D. project. At 5:45 a.m. I let them know I wouldn’t be coming in, feeling a wave of guilt. “How did I get here?” I wondered. It surprises us to learn how much literature was penned in the trenches of World War I. The poems of Wilfred Owen or the early tales of Tolkien, for example, are all the more exceptional when we consider that they were composed amid states of mortal terror. But the most incredible and most stupefying example perhaps is Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Less than a hundred pages long, it is a slender book that, according to its author, set about to find a “final solution” to the problems of philosophy (a phrase made even more cryptic by the knowledge that Wittgenstein and Hitler were once schoolmates). And indeed, when the Tractatus was published in the fall of 1921, Wittgenstein effectively “retired” from his trade, believing that he’d found the basement of Western philosophy and had turned off the lights when he left.

It surprises us to learn how much literature was penned in the trenches of World War I. The poems of Wilfred Owen or the early tales of Tolkien, for example, are all the more exceptional when we consider that they were composed amid states of mortal terror. But the most incredible and most stupefying example perhaps is Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Less than a hundred pages long, it is a slender book that, according to its author, set about to find a “final solution” to the problems of philosophy (a phrase made even more cryptic by the knowledge that Wittgenstein and Hitler were once schoolmates). And indeed, when the Tractatus was published in the fall of 1921, Wittgenstein effectively “retired” from his trade, believing that he’d found the basement of Western philosophy and had turned off the lights when he left.

A supply chain is like a Rorschach Test: each economic analyst sees in it a pattern reflecting his or her own preconceptions. This may be inevitable, since everyone is a product of differing educations, backgrounds, and prejudices. But some observed patterns are more plausible than others.

A supply chain is like a Rorschach Test: each economic analyst sees in it a pattern reflecting his or her own preconceptions. This may be inevitable, since everyone is a product of differing educations, backgrounds, and prejudices. But some observed patterns are more plausible than others. We’re doing astonishingly well, and most environmental trends are going in the right direction. Carbon emissions have declined more in the United States than in any other country over the last twenty years, mostly due to fracking. Carbon emissions peaked in Europe in the mid-seventies, in the main European countries I should say. And some people think carbon emissions have peaked globally. I personally think they probably have another ten years of growth, but we’re close to global peak emissions, after which they will go down. We appear to be at peak agricultural land use, and that will go down. So Malthus was sort of spectacularly wrong, both on human progress, but also environmental progress.

We’re doing astonishingly well, and most environmental trends are going in the right direction. Carbon emissions have declined more in the United States than in any other country over the last twenty years, mostly due to fracking. Carbon emissions peaked in Europe in the mid-seventies, in the main European countries I should say. And some people think carbon emissions have peaked globally. I personally think they probably have another ten years of growth, but we’re close to global peak emissions, after which they will go down. We appear to be at peak agricultural land use, and that will go down. So Malthus was sort of spectacularly wrong, both on human progress, but also environmental progress.