Rachel Cooke in The Guardian:

Away from the sulphurous world of Twitter, the feminist campaigner and journalist Julie Bindel is best known as the co-founder of Justice for Women, an organisation that since 1990 has advocated for those convicted of murder after having experienced violence by men; JfW campaigned successfully for the release of Emma Humphreys, who killed her violent pimp, Trevor Armitage, in 1985, and more recently for Sally Challen, who was convicted of the murder of her abusive husband, Richard, in 2010. Thanks to this work, and to her reporting elsewhere, Bindel also has expertise in the areas of porn, prostitution and sex trafficking; she was one of those who helped to break the story of the grooming gangs operating in the north of England, an investigation that would eventually lead to the independent inquiry into child sexual exploitation in Rotherham in 2013.

Away from the sulphurous world of Twitter, the feminist campaigner and journalist Julie Bindel is best known as the co-founder of Justice for Women, an organisation that since 1990 has advocated for those convicted of murder after having experienced violence by men; JfW campaigned successfully for the release of Emma Humphreys, who killed her violent pimp, Trevor Armitage, in 1985, and more recently for Sally Challen, who was convicted of the murder of her abusive husband, Richard, in 2010. Thanks to this work, and to her reporting elsewhere, Bindel also has expertise in the areas of porn, prostitution and sex trafficking; she was one of those who helped to break the story of the grooming gangs operating in the north of England, an investigation that would eventually lead to the independent inquiry into child sexual exploitation in Rotherham in 2013.

All of which surely makes her a Good Thing: a person of integrity, bravery and determination. But alas, as she writes in her new book, Feminism for Women, there are people for whom none of this is relevant. To them, Bindel is a Bad Thing, and they would like her to disappear – if not from the world, then at least from public life. In recent years, she has been de-platformed by numerous universities and other institutions following protests by assorted trans activists and their allies, among them those who argue that “sex work is work”. Even when such events do go ahead, there’s often trouble. At one, a man tried to punch her in the face. At another, a debate about pornography, her opponent, a man who has made money in that industry, was given a warm welcome by the students who’d tried so hard to get her taken off the bill. What, you might well wonder, has she done to invoke such anger, disapproval and bizarre contrarianism? Why does her past now count for so little? Is it really such a crime to believe, as she does, that sex is a material reality, and gender a social construct?

More here.

In one sentence, then, here’s my beef with The Chair: its script portrays a mob, step by step, destroying an innocent man’s life over nothing, and yet it wants me to feel the mob’s pain, and be disappointed in its victim for mulishly insisting on his innocence (even though he is, in fact, innocent).

In one sentence, then, here’s my beef with The Chair: its script portrays a mob, step by step, destroying an innocent man’s life over nothing, and yet it wants me to feel the mob’s pain, and be disappointed in its victim for mulishly insisting on his innocence (even though he is, in fact, innocent).

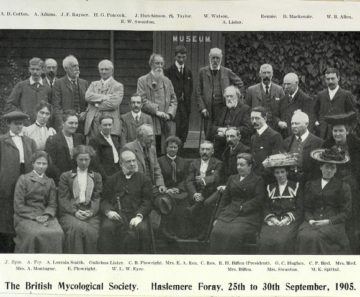

The pioneer of slime mould research was an extraordinary mycologist called Gulielma Lister (1860-1949). Like many female scientists, she has vanished into near obscurity, yet her colleagues celebrated her as the “Queen of Slime Moulds.” In 1905, she was among the first 25 women admitted as a Fellow of London’s prestigious Linnean Society. She made quite an impression on that august group: one younger admirer remembered that she “removed her hat in deference to the sexless character of a Fellow. It was an unusual thing then for a lady to remove her hat, but we all took our cue from Miss Lister and did the same.” She broke the conventions of her time, and a century later her research lies behind a major new approach to computer software.

The pioneer of slime mould research was an extraordinary mycologist called Gulielma Lister (1860-1949). Like many female scientists, she has vanished into near obscurity, yet her colleagues celebrated her as the “Queen of Slime Moulds.” In 1905, she was among the first 25 women admitted as a Fellow of London’s prestigious Linnean Society. She made quite an impression on that august group: one younger admirer remembered that she “removed her hat in deference to the sexless character of a Fellow. It was an unusual thing then for a lady to remove her hat, but we all took our cue from Miss Lister and did the same.” She broke the conventions of her time, and a century later her research lies behind a major new approach to computer software.

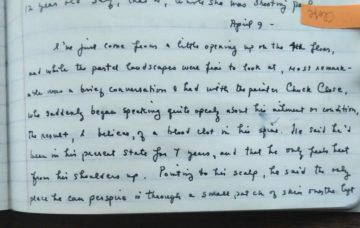

I’ve just come from a little opening up on the fourth floor, and while the pastel landscapes were fine to look at, most remarkable was a brief conversation I had with the painter Chuck Close, who suddenly began speaking quite openly about his ailment or condition, the result, I believe, of a blood clot in his spine. He said he’s been in his present state for seven years, and that he only feels heat from his shoulders up. Pointing to his scalp, he said the only place he can perspire is through a small patch of skin on the left side of his head. When he is touched anywhere below his shoulders, what he feels is an icy cold. He is happiest in the sun in his bathing suit.

I’ve just come from a little opening up on the fourth floor, and while the pastel landscapes were fine to look at, most remarkable was a brief conversation I had with the painter Chuck Close, who suddenly began speaking quite openly about his ailment or condition, the result, I believe, of a blood clot in his spine. He said he’s been in his present state for seven years, and that he only feels heat from his shoulders up. Pointing to his scalp, he said the only place he can perspire is through a small patch of skin on the left side of his head. When he is touched anywhere below his shoulders, what he feels is an icy cold. He is happiest in the sun in his bathing suit. T

T A

A SAN FRANCISCO — After four years, repeated delays and the birth of her baby,

SAN FRANCISCO — After four years, repeated delays and the birth of her baby,  Dear Readers,

Dear Readers, Philosophers are prone to define

Philosophers are prone to define  This week I had planned to present the 3 Quarks Daily readership with a fluffy little piece about my memories of a grade school foreign language teacher. It was poignant, it was heartfelt, it was funny (if I do say so myself). Above all, it was intended as a brief respite from the nonstop parade of horrors scrolling past our screens every day—a parade in which my own recent writings have occupied a lavishly decorated float. We all deserve a break, I thought. It would be nice to look at some baton twirlers for a minute, listen to an oompa band.

This week I had planned to present the 3 Quarks Daily readership with a fluffy little piece about my memories of a grade school foreign language teacher. It was poignant, it was heartfelt, it was funny (if I do say so myself). Above all, it was intended as a brief respite from the nonstop parade of horrors scrolling past our screens every day—a parade in which my own recent writings have occupied a lavishly decorated float. We all deserve a break, I thought. It would be nice to look at some baton twirlers for a minute, listen to an oompa band.

Sughra Raza. Karachi Afternoon Sun, 2010.

Sughra Raza. Karachi Afternoon Sun, 2010.