Month: August 2021

From pirates to ransomware: the secret economics of extortion

Tom Standage in More Intelligent Life:

In 74bc a band of pirates made a terrible mistake when they captured a ship off the coast of Asia Minor, now Turkey. They kidnapped one of the passengers, a young Roman citizen named Julius Caesar, along with his entourage, and demanded a ransom of 20 talents (about 650kg in silver) for his release. Caesar, in his mid-20s and on his way to study rhetoric in Rhodes, burst out laughing. Didn’t they know who he was? He was worth 50 talents, not a mere 20! Unsurprisingly the pirates agreed to this higher ransom, and released some of Caesar’s associates to raise the money.

In 74bc a band of pirates made a terrible mistake when they captured a ship off the coast of Asia Minor, now Turkey. They kidnapped one of the passengers, a young Roman citizen named Julius Caesar, along with his entourage, and demanded a ransom of 20 talents (about 650kg in silver) for his release. Caesar, in his mid-20s and on his way to study rhetoric in Rhodes, burst out laughing. Didn’t they know who he was? He was worth 50 talents, not a mere 20! Unsurprisingly the pirates agreed to this higher ransom, and released some of Caesar’s associates to raise the money.

Pirates were the scourge of the Mediterranean, bribing their way around efforts to suppress them. But despite their fearsome reputation, Caesar refused to be intimidated. He told them to be quiet when he wanted to sleep, “as if the men were not his watchers, but his royal bodyguard”, writes Plutarch. He joined in their games and regaled them with speeches and poetry, mocking them as illiterate barbarians. Once he was free, he said, he would execute the lot of them. According to Plutarch, “the pirates were delighted at this, and attributed his boldness of speech to a certain simplicity and boyish mirth.”

When Caesar’s friends arrived with the ransom the pirates released him. He went straight to Miletus, a city on the coast of Asia Minor, raised a fleet and returned to the pirates’ camp. After helping himself to their treasure, he captured most of the pirates, took them to the city of Pergamon and asked the local governor to execute them. When the governor wavered, Caesar had the pirates crucified, even though he lacked permission to do so.

More here.

What Google Could Learn from a Fruit Fly

Christie Wilcox in Nautilus:

Let’s say you’re at a big office party full of people, both coworkers and strangers, when someone walks up to you. You have a split second to determine if you know this person or not; you don’t want to make the faux pas of re-introducing yourself to your receptionist. Luckily, your brain is adept at what computer scientists call “novelty detection”—the ability to distinguish new information from details that have been encountered before. Most of the time we do it effortlessly. How exactly that skill works is a provocative scientific mystery, however.

Let’s say you’re at a big office party full of people, both coworkers and strangers, when someone walks up to you. You have a split second to determine if you know this person or not; you don’t want to make the faux pas of re-introducing yourself to your receptionist. Luckily, your brain is adept at what computer scientists call “novelty detection”—the ability to distinguish new information from details that have been encountered before. Most of the time we do it effortlessly. How exactly that skill works is a provocative scientific mystery, however.

Novelty detection is useful in all kinds of other settings, including ones that have nothing to do with social interactions. If you’re getting a mammogram, you want your radiologist and any image-analysis software she uses to be good at novelty detection, so she can accurately spot any mass that shouldn’t be there. If you’re shopping in a store, you want your credit card company to have good novelty detection, too. It’s nice that they are on the lookout for fraudulent transactions, but it would be nicer if they didn’t shut down your card every time you drive an hour away from home.

It just so happens that all of these detectors—your brain, medical analysis programs, and credit card fraud detectors—rely on similar algorithms to find new and unusual things. The main difference is that your brain’s novelty detection algorithm is much more accurate and efficient than the programmed ones, at least for now. Computer scientists like Saket Navlakha are therefore working to better understand the algorithms that succeed so well in biology, and then reverse-engineer them to improve the ones in our technology.

More here.

In memoriam: Syed Afzel Hussain Naqvi

Feisal Naqvi in The News:

My father died at 2:15 pm last Sunday. I would like to say that he died in my arms, but the truth is that by the time I heard my sister scream and ran in from the next room, he had already moved on from this world.

My father died at 2:15 pm last Sunday. I would like to say that he died in my arms, but the truth is that by the time I heard my sister scream and ran in from the next room, he had already moved on from this world.

Every father looms large in the imagination of his children. But my father was larger than life in every way. He was 6′ 3″ and born 86 years ago when such height was more unusual than it is now. More relevantly, he carried all of us and our troubles like an unruffled Atlas. And by all of us, I mean not just his children or even his children’s children. I mean the entire extended clan of people he was related to as well as humanity beyond the ties of blood. There was no cousin too distant for him to not keep tabs on. He was the one man making sure that no child was left behind. Even in our village, he financed three schools and was never happier than when he could dragoon one of his many descendants into contributing more.

More here.

On Subjectivity And A Visit To Kierkegaard’s Grave

Meghan O’Gieblyn at Bookforum:

The question of subjectivity had been very much on my mind that summer. A few months earlier I’d been commissioned by a magazine to review several new books on consciousness. All of the authors were men, and I was surprised by how often they acknowledged the deeply personal motivations that led them to their preferred theories of mind. Two of them, in a bizarre parallel, listed among these motivations the desire to leave their wives. The first was Out of My Head, by Tim Parks, a novelist who had become an advocate for spread mind theory—a minority position that holds that consciousness exists not solely in the brain but also in the object of perception. Parks claimed that he first became interested in this theory around the time he left his wife for a younger woman, a decision that his friends chalked up to a midlife crisis. He believed the problem was his marriage—something in the objective world—while everyone else insisted that the problem was inside his head. “It seems to me that these various life events,” he wrote, “might have predisposed me to be interested in a theory of consciousness and perception that tends to give credit to the senses, or rather to experience.”

The question of subjectivity had been very much on my mind that summer. A few months earlier I’d been commissioned by a magazine to review several new books on consciousness. All of the authors were men, and I was surprised by how often they acknowledged the deeply personal motivations that led them to their preferred theories of mind. Two of them, in a bizarre parallel, listed among these motivations the desire to leave their wives. The first was Out of My Head, by Tim Parks, a novelist who had become an advocate for spread mind theory—a minority position that holds that consciousness exists not solely in the brain but also in the object of perception. Parks claimed that he first became interested in this theory around the time he left his wife for a younger woman, a decision that his friends chalked up to a midlife crisis. He believed the problem was his marriage—something in the objective world—while everyone else insisted that the problem was inside his head. “It seems to me that these various life events,” he wrote, “might have predisposed me to be interested in a theory of consciousness and perception that tends to give credit to the senses, or rather to experience.”

more here.

An Astonishing Dual Portrait of a Poet and His City

Richard Brody at The New Yorker:

Every great urban filmmaker has a personal metaphysics of the city, a sense that the synergies and mysteries of urban life can find their ideal form in images. That’s what Pola Rapaport reveals in her first feature, “Broken Meat,” from 1991, which is showing, starting Wednesday, on Metrograph’s virtual cinema (with her introduction) and is also streaming on Vimeo.

Every great urban filmmaker has a personal metaphysics of the city, a sense that the synergies and mysteries of urban life can find their ideal form in images. That’s what Pola Rapaport reveals in her first feature, “Broken Meat,” from 1991, which is showing, starting Wednesday, on Metrograph’s virtual cinema (with her introduction) and is also streaming on Vimeo.

It’s a film in a particular and too often narrowing mode: a documentary portrait of an artist, the poet Alan Granville, whose work doesn’t appear to have attracted much attention beyond the movie itself. “Broken Meat” is the title of one of his works, which Rapaport reads, during a train ride, early in the film. The poet’s obscurity itself comes off as something of his life’s work, his self-chosen destiny, as he describes his lifelong hero, Vincent van Gogh. Considering a reproduction of a self-portrait that adorns his wall, Granville says that van Gogh’s gaze is not “disturbed” but “steadfast,” and that the artist awakened Granville’s “first awareness that a person could lead an undiscovered life.” Granville acknowledges that he himself is “largely an unfulfilled poet,” with no realistic hope of recognition, and the gap between his vast literary aspirations and his actual circumstances is the documentary’s anguished drama.

more here.

Broken Meat

The best books about the post-human Earth

Cal Flyn in The Guardian:

We humans have a profound impact on the world around us. Bob Paine, the groundbreaking American ecologist, once described us as a “hyperkeystone” species: our actions affect the lives and habitats of other creatures more than any other species on Earth. So much so, some scientists have adopted the term Anthropocene to refer to the current era, defined by atomic testing, the climate crisis and the development of plastics. Evidence of human activity will survive long after we are gone, both within the fossil record and in the state of the planet more generally, which we will have influenced in long-reaching and unpredictable ways.

We humans have a profound impact on the world around us. Bob Paine, the groundbreaking American ecologist, once described us as a “hyperkeystone” species: our actions affect the lives and habitats of other creatures more than any other species on Earth. So much so, some scientists have adopted the term Anthropocene to refer to the current era, defined by atomic testing, the climate crisis and the development of plastics. Evidence of human activity will survive long after we are gone, both within the fossil record and in the state of the planet more generally, which we will have influenced in long-reaching and unpredictable ways.

There is some wonderful writing on this subject, not least David Farrier’s Footprints, a fascinating nonfiction book that seeks to predict the traces we will leave behind: from the nuclear waste sealed deep within concrete tombs to the future rust-stained remains of our megacities. The World Without Us by Alan Weisman was a 2007 mega-bestseller along similar lines, which asks what would happen if, for some unspecified reason, all humans disappeared from the planet tomorrow. Drawing from hundreds of interviews with engineers, scientists and archaeologists, it unfolds like a thriller: bridges collapse, subway tunnels flood, skyscrapers fall to the ground.

More here.

This Physicist Discovered an Escape From Hawking’s Black Hole Paradox

Natalie Wolchover in Quanta:

In 1974, Stephen Hawking calculated that black holes’ secrets die with them. Random quantum jitter on the spherical outer boundary, or “event horizon,” of a black hole will cause the hole to radiate particles and slowly shrink to nothing. Any record of the star whose violent contraction formed the black hole — and whatever else got swallowed up after — then seemed to be permanently lost.

In 1974, Stephen Hawking calculated that black holes’ secrets die with them. Random quantum jitter on the spherical outer boundary, or “event horizon,” of a black hole will cause the hole to radiate particles and slowly shrink to nothing. Any record of the star whose violent contraction formed the black hole — and whatever else got swallowed up after — then seemed to be permanently lost.

Hawking’s calculation posed a paradox — the infamous “black hole information paradox” — that has motivated research in fundamental physics ever since. On the one hand, quantum mechanics, the rulebook for particles, says that information about particles’ past states gets carried forward as they evolve — a bedrock principle called “unitarity.” But black holes take their cues from general relativity, the theory that space and time form a bendy fabric and gravity is the fabric’s curves. Hawking had tried to apply quantum mechanics to particles near a black hole’s periphery, and saw unitarity break down.

So do evaporating black holes really destroy information, meaning unitarity is not a true principle of nature? Or does information escape as a black hole evaporates?

More here.

Toward a Binational Alternative in Israel: On the Illusion of the Two State Solution

Omri Boehm in Literary Hub:

In the 25years that have passed since the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, his two-state Oslo legacy has been driven into the ground. In 1993, when the agreement was first signed, approximately 110,000 settlers were living in the West Bank, and 146,000 were living in occupied territories surrounding Jerusalem. By now, the numbers have increased to approximately 400,000 settlers in the West Bank and 300,000 around Jerusalem. This situation will not be reversed. In 2021, roughly 10 percent of Israel’s Jewish population lives on occupied territory—subject to Israeli law, represented by Israel’s parliament—and enjoys the opportunities and prosperity of a flourishing first-world country, with public schools, factories, banks, a system of highways, and a research university at their disposal. Around them, however, are almost 3 million Palestinians who, for 53 years now, have lived under Israel’s aggressive military regime.

In the 25years that have passed since the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, his two-state Oslo legacy has been driven into the ground. In 1993, when the agreement was first signed, approximately 110,000 settlers were living in the West Bank, and 146,000 were living in occupied territories surrounding Jerusalem. By now, the numbers have increased to approximately 400,000 settlers in the West Bank and 300,000 around Jerusalem. This situation will not be reversed. In 2021, roughly 10 percent of Israel’s Jewish population lives on occupied territory—subject to Israeli law, represented by Israel’s parliament—and enjoys the opportunities and prosperity of a flourishing first-world country, with public schools, factories, banks, a system of highways, and a research university at their disposal. Around them, however, are almost 3 million Palestinians who, for 53 years now, have lived under Israel’s aggressive military regime.

Even intransigent two-state supporters agree that not all of these settlers can be evacuated, but they insist that the challenge posed by their presence is exaggerated. On this view, whereas the West Bank’s map is stained by approximately 130 spots marking Israeli settlements, about 110 of them count populations of less than 5,000. Another 60 settlements, the argument goes, have populations of less than 1,000, and many of them are, in the first place, located next to the 1967 border: by introducing only minor corrections to the border, it is allegedly possible to leave most settlers within Israel’s proper territory, and to compensate the Palestinians with other pieces of land from other areas. Given this, it is claimed that the tendency to “grossly overstate” the obstacle that settlements pose to a future two-state solution is based not on a sober analysis of the situation, but on an ideological support of one-state politics.

Unfortunately, this optimism is itself highly ideological, and can only be preserved if one avoids a careful look at the map.

More here.

Jonathan Haidt: How the Modern World Makes Us Mentally Ill

Rethinking The Friendship Plot

B.D. McClay at Lapham’s Quarterly:

Still, where friendship operates as a code, it is still present as text. These stories are still “about” friendship, after all, and so friendship steadily accrues these myths along with whatever it’s meant to insinuate. And because friendship begins to seem like an off road into an alternate adulthood—or no adulthood at all—the friendship plot’s most congenial home is children’s literature, followed by books that concern themselves with childhood. Read through the lens of the friendship plot, many books that either are childhood classics or focus on childhood reveal themselves as stories that portray the end of childhood and initiation into adulthood as the death or abandonment of a beloved friend.

Still, where friendship operates as a code, it is still present as text. These stories are still “about” friendship, after all, and so friendship steadily accrues these myths along with whatever it’s meant to insinuate. And because friendship begins to seem like an off road into an alternate adulthood—or no adulthood at all—the friendship plot’s most congenial home is children’s literature, followed by books that concern themselves with childhood. Read through the lens of the friendship plot, many books that either are childhood classics or focus on childhood reveal themselves as stories that portray the end of childhood and initiation into adulthood as the death or abandonment of a beloved friend.

Sometimes this friend isn’t human. A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh stories end with the disappearance of Christopher Robin, The Velveteen Rabbit with the rabbit and his boy parting ways after the boy almost dies of scarlet fever and his childhood is—quite literally—consumed by flame.

more here.

The Gallery of Miracles and Madness

Charles Darwent at Literary Review:

In 1908, Paul Klee, struggling as a painter, saw his first van Gogh canvas at a gallery in Munich. The Dutchman’s genius was at once clear to him; so, too, and inseparably, was his madness. ‘Pathetic to the point of being pathological,’ Klee wrote, ‘this endangered man’ has a brain ‘consumed by the fire of a star’. Three years later, and shortly before joining them himself, Klee reviewed a show of works produced by the Blaue Reiter group. Once again, it was the irrational that drew his eye. ‘Neither childish behaviour nor madness are insulting words here, as they commonly are,’ Klee enthused. ‘All this is to be taken very seriously, more seriously than all the public galleries, when it comes to reforming today’s art.’

In 1908, Paul Klee, struggling as a painter, saw his first van Gogh canvas at a gallery in Munich. The Dutchman’s genius was at once clear to him; so, too, and inseparably, was his madness. ‘Pathetic to the point of being pathological,’ Klee wrote, ‘this endangered man’ has a brain ‘consumed by the fire of a star’. Three years later, and shortly before joining them himself, Klee reviewed a show of works produced by the Blaue Reiter group. Once again, it was the irrational that drew his eye. ‘Neither childish behaviour nor madness are insulting words here, as they commonly are,’ Klee enthused. ‘All this is to be taken very seriously, more seriously than all the public galleries, when it comes to reforming today’s art.’

A decade later, the polymath Oskar Schlemmer, shortly to take up a teaching post at the new Bauhaus in Weimar, went to a slide show of images of the art of the insane. What he saw in Stuttgart that night stirred him to ecstasy.

more here.

In Our Time: Automata

Being You – the exhilarating new science of consciousness

Gaia Vince in The Guardian:

For every stoner who has been overcome with profound insight and drawled, “Reality is a construct, maaan,” here is the astonishing affirmation. Reality – or, at least, our perception of it – is a “controlled hallucination”, according to the neuroscientist Anil Seth. Everything we see, hear and perceive around us, our whole beautiful world, is a big lie created by our deceptive brains, like a forever version of The Truman Show, to placate us into living our lives. Our minds invent for us a universe of colours, sounds, shapes and feelings through which we interact with our world and relate to each other, Seth argues. We even invent ourselves. Our reality, then, is an illusion, and understanding this involves tackling the thorny issue of consciousness: what it means to, well, be.

For every stoner who has been overcome with profound insight and drawled, “Reality is a construct, maaan,” here is the astonishing affirmation. Reality – or, at least, our perception of it – is a “controlled hallucination”, according to the neuroscientist Anil Seth. Everything we see, hear and perceive around us, our whole beautiful world, is a big lie created by our deceptive brains, like a forever version of The Truman Show, to placate us into living our lives. Our minds invent for us a universe of colours, sounds, shapes and feelings through which we interact with our world and relate to each other, Seth argues. We even invent ourselves. Our reality, then, is an illusion, and understanding this involves tackling the thorny issue of consciousness: what it means to, well, be.

Consciousness has long been the preserve of philosophers and priests, poets and artists; now neuroscientists are investigating the mysterious quality and trying to answer the hard question of how consciousness arises in the first place. If this all sounds a bit hard going, it’s actually not at all in the masterly hands of Seth, who deftly weaves the philosophical, biological and personal with a lucid clarity and coherence that is thrilling to read.

Consciousness, which Seth defines as “any kind of subjective experience whatsoever”, is central to our being and identity as animate sentient creatures. What does it mean for you to be you, as opposed to being a stone or a bat? And how does this feeling of being you emerge from the squishy conglomeration of cells we keep in our skulls? Science has shied away from these sorts of intrinsically experiential questions, partly because it’s not obvious how science’s tools could explore them. Scientists are fond of pursuing “objective” truths and realities, not probing the perspectival realms of subjectivity to seek the truth of nostalgia, joy or the perfect blueness of an Yves Klein canvas. Also, it’s hard. Seth might use other words, but essentially, he is exploring the science of people’s souls – a daunting task.

More here.

Fraudulent data raise questions about superstar honesty researcher

Cathleen O’Grady in Science:

The 2012 paper, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), reported a field study for which an unnamed insurance company purportedly randomized 13,488 customers to sign an honesty declaration at either the top or bottom of a form asking for an update to their odometer reading. Those who signed at the top were more honest, according to the study: They reported driving 2428 miles (3907 kilometers) more on average than those who signed at the bottom, which would result in a higher insurance premium. The paper also contained data from two lab experiments showing similar results from upfront honesty declarations.

The Obama administration’s Social and Behavioral Sciences Team recommended the intervention as a “nonfinancial incentive” to improve honesty, for instance on tax declarations, in its 2016 annual report. Lemonade, an insurance company, hired Ariely as its “chief behavioral officer.” But several other studies found that an upfront honesty declaration did not lead people to be more truthful; one even concluded it led to more false claims.

After discovering the result didn’t replicate in what he thought would be a “straightforward” extension study, one of the authors of the PNAS paper, Harvard Business School behavioral scientist Max Bazerman, asked the other authors to collaborate on a replication of one of their two lab experiments. This time, the team found no effects on honesty, it reported in 2020, again in PNAS.

While conducting the new lab study, Harvard Business School Ph.D. student Ariella Kristal found an odd detail in the original field study: Customers asked to sign at the top had significantly different baseline mileages—about 15,000 miles lower on average—than customers who signed at the bottom. The researchers reported this as a possible randomization failure in the 2020 paper, and also published the full data set.

Some time later, a group of anonymous researchers downloaded those data, according to last week’s post on Data Colada. A simple look at the participants’ mileage distribution revealed something very suspicious. Other data sets of people’s driving distances show a bell curve, with some people driving a lot, a few very little, and most somewhere in the middle. In the 2012 study, there was an unusually equal spread: Roughly the same number of people drove every distance between 0 and 50,000 miles. “I was flabbergasted,” says the researcher who made the discovery. (They spoke to Science on condition of anonymity because of fears for their career.)

Worrying that PNAS would not investigate the issue thoroughly, the whistleblower contacted the Data Colada bloggers instead, who conducted a follow-up review that convinced them the field study results were statistically impossible.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

All the Carefully Measured Seconds

Back then I still believed it was possible

to prevent certain things, until that hot afternoon.

It was the middle of grain harvest, August of ’54,

when Fred climbed down from his stalled combine

and took off for Montrose to buy a part.

Later I realized the part was a ruse of fate, like

something made up to get someone to a surprise party.

So many times I reran those last hours,

adding or subtracting a few seconds here or there.

Lingering a moment in the field, he could have

noticed the grain shiver as a cloud passed by,

he could have paused by the barn to admire the blue

and lavender flecks adorning the pigeon’s throats,

he could have stopped by the house to finger

the soft leaves of African violets

on the sill, he could have slipped his arm

around Ella’s waist as she stood at the sink,

her hands in the dishwater.

But, he swatted the grain dust from his overalls

and climbed into his green Buick to keep

his appointment on Highway 38. Even then,

it was not too late. He could have floored

the car just this once, he could have let

the wind rush in, raising his sparse strands

of matted hair to dance in the breeze.

When I saw Fred’s car again, it looked as if

it had been punched by the fist of some god

though surely not the same one who keeps

the earth spinning, the sun and moon rising,

passion ascending to fuse new life,

the rose unfolding with tenderness,

the worm tilling the orchard floor,

all the carefully measured seconds

adding up exactly to us.

by Josephine Redlin

from Ploughshares, Sping 1995

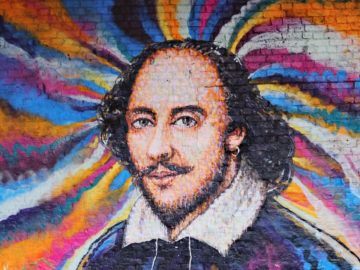

How Data Science Pinpointed the (unexpected) Creepiest Word in “Macbeth”

Clive Thompson in OneZero:

Macbeth is a creepy play.

Macbeth is a creepy play.

Actors have long been superstitious about acting in it. That’s partly because performances have been riddled with accidents and fatalities; indeed, actors consider it bad luck to even utter the name of the play. (They call it “The Scottish Tragedy”.) And it’s partly because the basic substance of the plot is eldritch: You’ve got black magic, witches, a gore-flecked ghost and walking forests.

But fans of Macbeth often say its freaky qualities are deeper than just the plot devices and characters. For centuries, people been unsettled by the very language of the play.

Actors and critics have long remarked that when you read Macbeth out loud, it feels like your voice and mouth and brain are doing something ever so slightly wrong. There’s something subconsciously off about the sound of the play, and it spooks people. It’s as if Shakespeare somehow wove a tiny bit of creepiness into every single line. The literary scholar George Walton Williams described the “continuous sense of menace” and “horror” that pervades even seemingly innocuous scenes.

For centuries, Shakespeare fans and theater folk have wondered about this, but could never quite explain it.

Then a clever bit of data analysis in 2014 uncovered the reason. (The paper is here.)

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: W. Brian Arthur on Complexity Economics

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Economies in the modern world are incredibly complex systems. But when we sit down to think about them in quantitative ways, it’s natural to keep things simple at first. We look for reliable relations between small numbers of variables, seek equilibrium configurations, and so forth. But those approaches don’t always work in complex systems, and sometimes we have to use methods that are specifically adapted to the challenges of complexity. That’s the perspective of W. Brian Arthur, a pioneer in the field of complexity economics, according to which economies are typically not in equilibrium, not made of homogeneous agents, and are being constantly updated. We talk about the basic ideas of complexity economics, how it differs from more standard approaches, and what it teaches us about the operation of real economies.

Economies in the modern world are incredibly complex systems. But when we sit down to think about them in quantitative ways, it’s natural to keep things simple at first. We look for reliable relations between small numbers of variables, seek equilibrium configurations, and so forth. But those approaches don’t always work in complex systems, and sometimes we have to use methods that are specifically adapted to the challenges of complexity. That’s the perspective of W. Brian Arthur, a pioneer in the field of complexity economics, according to which economies are typically not in equilibrium, not made of homogeneous agents, and are being constantly updated. We talk about the basic ideas of complexity economics, how it differs from more standard approaches, and what it teaches us about the operation of real economies.

More here.