by Mike O’Brien

Last month I took a trip that had a profound impact on me. Departing from a small staircase, my short flight had stopovers on the edge of a sofa and a magazine rack, before finally reaching my final destination on the floor. Being the overly intellectual sort that I am, I proceeded though most of the itinerary head-first. As soon as it was over, I questioned how best to process the experience, and how it might change me as a person, going forward. (Lord, how I despise that expression. As if freezing or going backwards were options, plutonium-powered Deloreans notwithstanding.) I didn’t seek medical attention, given that I was half-vaxed at the time and not disposed to sitting in hospital waiting rooms with the Delta variant coming into bloom.

I had taken a similar voyage to the floor years ago, and knew the protocols for returning. The last time, I adhered as closely as possible to a 10-14 day regimen of silence, darkness, sleep and dietary fat, with an absolute prohibition on screens, reading, physical activity and alcohol. This is a much more stringent regimen than those prescribed by most Canadian health guidelines regarding concussions, for the same reason that dairy-producing countries prescribe more cheese in a balanced diet. To whit, if Canadian health authorities took the long-term effects of concussions seriously, we would have to cancel North-American-style hockey and football (and boxing and MMA and Judo and racing and that competition where Russians slap each other really hard), and any professional league with money in its pockets would be sued into oblivion.

I do take the long-term effects of concussions seriously, having taken a heap of psychology classes at the very neurologically-inclined McGill University (Go Martlets!), and having done a fair bit of rather rough martial arts (safely). Concussions scare the living daylights out of me, and I’m struck by the tone of much public health information on the subject, which seem to be structured around the question of when Timmy can lace up his skates again. Read more »

In spite of my abiding interest in literature when I came to college I was vaguely inclined to major in History. In the long break between school and college I chanced upon two books of Marxist history which opened me to a new vista of looking at history. The first was Maurice Dobb’s Studies in the Development of Capitalism. This book showed me that there is a discernible pattern in the jumble of facts in history, which attracted me. Soon after, I read a lesser Marxist history book, A.L. Morton’s People’s History of England which showed me how recasting the old widely-known history of England from the people’s perspective gives you new insights. These books whetted my appetite to read more of Marxist history.

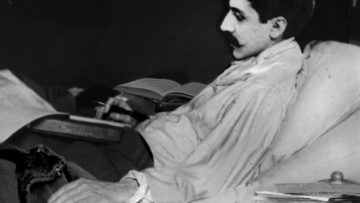

In spite of my abiding interest in literature when I came to college I was vaguely inclined to major in History. In the long break between school and college I chanced upon two books of Marxist history which opened me to a new vista of looking at history. The first was Maurice Dobb’s Studies in the Development of Capitalism. This book showed me that there is a discernible pattern in the jumble of facts in history, which attracted me. Soon after, I read a lesser Marxist history book, A.L. Morton’s People’s History of England which showed me how recasting the old widely-known history of England from the people’s perspective gives you new insights. These books whetted my appetite to read more of Marxist history. Marcel Proust represents many things. Chief among these perhaps, especially for non-French readers, is quantity, and therefore the marathon-like endurance of anyone who actually reads all seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time, and can prove it. A 2016 cartoon in the New Yorker features a middle-aged couple sitting up in bed when one of them realises he and his partner are exactly the age at which they must start the opus if they hope to finish it before death. In a classic Looney Tunes episode Bugs Bunny has sent Elmer Fudd into a dustcloud of St. Vitus-like commotion from which he cannot escape; the sheer temporal extension of Fudd’s state is marked by Bugs sitting down next to him and patiently opening the cover of Remembrance of Things Past (as it used to be called in English).

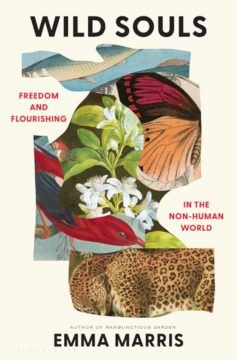

Marcel Proust represents many things. Chief among these perhaps, especially for non-French readers, is quantity, and therefore the marathon-like endurance of anyone who actually reads all seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time, and can prove it. A 2016 cartoon in the New Yorker features a middle-aged couple sitting up in bed when one of them realises he and his partner are exactly the age at which they must start the opus if they hope to finish it before death. In a classic Looney Tunes episode Bugs Bunny has sent Elmer Fudd into a dustcloud of St. Vitus-like commotion from which he cannot escape; the sheer temporal extension of Fudd’s state is marked by Bugs sitting down next to him and patiently opening the cover of Remembrance of Things Past (as it used to be called in English). I was once challenged by a friend to explain why it matters if species go extinct. Flustered, I launched into a rambling monologue about the intrinsic value of life and the importance of biodiversity for creating functioning ecosystems that ultimately prop up human economies. I don’t remember what my friend said; he certainly didn’t declare himself a born-again conservationist on the spot. But I do remember feeling frustrated that, in my inability to articulate a specific reason, I had somehow let down not only myself, but the entire planet.

I was once challenged by a friend to explain why it matters if species go extinct. Flustered, I launched into a rambling monologue about the intrinsic value of life and the importance of biodiversity for creating functioning ecosystems that ultimately prop up human economies. I don’t remember what my friend said; he certainly didn’t declare himself a born-again conservationist on the spot. But I do remember feeling frustrated that, in my inability to articulate a specific reason, I had somehow let down not only myself, but the entire planet. Shortly before he died in 2007, the celebrated American novelist, iconoclast and second world war veteran Kurt Vonnegut gave a final interview. “My country is in ruins,” he said. “I’m a fish in a poisoned fishbowl.” Vonnegut was 84, and sounded razor sharp as he spoke about inequality and political shortsightedness, adding that in the history of the United States “one thing that no cabinet has ever had is a Secretary of the Future, and there are no plans at all for my children and grandchildren.”

Shortly before he died in 2007, the celebrated American novelist, iconoclast and second world war veteran Kurt Vonnegut gave a final interview. “My country is in ruins,” he said. “I’m a fish in a poisoned fishbowl.” Vonnegut was 84, and sounded razor sharp as he spoke about inequality and political shortsightedness, adding that in the history of the United States “one thing that no cabinet has ever had is a Secretary of the Future, and there are no plans at all for my children and grandchildren.” Throughout the pandemic, new surveillance systems—used by landlords, educational institutions, and employers—have converged, capturing new forms of data and exerting new forms of control in domestic spaces. COVID-19 prompted bosses and schools to accelerate the deployment of surveillance and tracking systems. As the pandemic drags on, many are still monitoring and assessing remote learners and workers in their most intimate environments. Landlords, meanwhile, took the pandemic as a time to promise “touchless” convenience and increased control over the homes of their tenants, rushing to install tracking systems in renters’ homes. Whatever the marketing promises, ultimately landlords’, bosses’, and schools’ intrusion of surveillance technologies into the home extends the carceral state into domestic spaces. In doing so, it also reveals the mutability of surveillance and assessment technologies, and the way the same systems can play many roles, while ultimately serving the powerful.

Throughout the pandemic, new surveillance systems—used by landlords, educational institutions, and employers—have converged, capturing new forms of data and exerting new forms of control in domestic spaces. COVID-19 prompted bosses and schools to accelerate the deployment of surveillance and tracking systems. As the pandemic drags on, many are still monitoring and assessing remote learners and workers in their most intimate environments. Landlords, meanwhile, took the pandemic as a time to promise “touchless” convenience and increased control over the homes of their tenants, rushing to install tracking systems in renters’ homes. Whatever the marketing promises, ultimately landlords’, bosses’, and schools’ intrusion of surveillance technologies into the home extends the carceral state into domestic spaces. In doing so, it also reveals the mutability of surveillance and assessment technologies, and the way the same systems can play many roles, while ultimately serving the powerful. On a recent afternoon, the comedian Jaboukie Young-White walked into Syndicated, a bar and movie theatre in Bushwick. He had bleach-blond hair and the beginnings of a mustache, and he wore workout clothes. “I like to exercise, but ‘I want to look plump and juicy’ isn’t enough motivation,” he said. “I need more of a narrative.” He had reserved a spot in a Muay Thai class nearby, but the class had been cancelled because of a sudden rainstorm. The gym’s owner texted him a video, and Young-White held up his phone: floor mats covered in gushing water. “Life during climate change, I guess,” he said, sliding into a booth. Two movie projectors beamed images onto a wall—“Fitzcarraldo,” the Werner Herzog film, next to “Whenever, Wherever,” the Shakira video. “Every bar should have this,” Young-White said. “If you’re on a first date and things get super awkward, you can at least look up and comment on something together, instead of each disappearing into your phones.”

On a recent afternoon, the comedian Jaboukie Young-White walked into Syndicated, a bar and movie theatre in Bushwick. He had bleach-blond hair and the beginnings of a mustache, and he wore workout clothes. “I like to exercise, but ‘I want to look plump and juicy’ isn’t enough motivation,” he said. “I need more of a narrative.” He had reserved a spot in a Muay Thai class nearby, but the class had been cancelled because of a sudden rainstorm. The gym’s owner texted him a video, and Young-White held up his phone: floor mats covered in gushing water. “Life during climate change, I guess,” he said, sliding into a booth. Two movie projectors beamed images onto a wall—“Fitzcarraldo,” the Werner Herzog film, next to “Whenever, Wherever,” the Shakira video. “Every bar should have this,” Young-White said. “If you’re on a first date and things get super awkward, you can at least look up and comment on something together, instead of each disappearing into your phones.” The case at hand that prevents me from an unqualified rooting for the category of “experience,” is the exemplary case of Malala Yousafzai of Pakistan, who has traversed the distance from female “experience” to feminist “expertise”, and who, like others before (and since) that have made that journey from the “margins” to the “center” of imperial power, has now switched from being a “voice of the oppressed” to becoming an “expert” who can speak to us and teach us about those authentic “other” women in the global south—in this case, Afghan women– to whom her prior proximity (“experience”)– renders her an “expert” on today. From experience to expertise then, is a pretty straightforward line, following the predictable path forged also by white feminism in thrall and service to imperial designs past and present. This is the path that was announced with great fanfare shortly after 9/11 by First Lady Laura Bush and enthusiastically supported by the Feminist Majority Foundation, that would “save brown women from brown men” by going in to the “backward” country of Afghanistan overrun by crazy “Moslem” men, in the process unleashing a 20-year war on the population that had had nothing to do with 9/11. The initial military intervention was then followed up over the next two decades with countless “development” schemes that enriched a few at the expense of the many, and when the cost of this unending war became unpopular with the citizenry “back home” in the USA over time—we left the hapless “natives” that included those very women we had been so concerned with “saving,” at the mercy of anarchy and chaos.

The case at hand that prevents me from an unqualified rooting for the category of “experience,” is the exemplary case of Malala Yousafzai of Pakistan, who has traversed the distance from female “experience” to feminist “expertise”, and who, like others before (and since) that have made that journey from the “margins” to the “center” of imperial power, has now switched from being a “voice of the oppressed” to becoming an “expert” who can speak to us and teach us about those authentic “other” women in the global south—in this case, Afghan women– to whom her prior proximity (“experience”)– renders her an “expert” on today. From experience to expertise then, is a pretty straightforward line, following the predictable path forged also by white feminism in thrall and service to imperial designs past and present. This is the path that was announced with great fanfare shortly after 9/11 by First Lady Laura Bush and enthusiastically supported by the Feminist Majority Foundation, that would “save brown women from brown men” by going in to the “backward” country of Afghanistan overrun by crazy “Moslem” men, in the process unleashing a 20-year war on the population that had had nothing to do with 9/11. The initial military intervention was then followed up over the next two decades with countless “development” schemes that enriched a few at the expense of the many, and when the cost of this unending war became unpopular with the citizenry “back home” in the USA over time—we left the hapless “natives” that included those very women we had been so concerned with “saving,” at the mercy of anarchy and chaos. Aditi Sahasrabuddhe in Phenomenal World (Photo by

Aditi Sahasrabuddhe in Phenomenal World (Photo by  Gernot Wagner in Bloomberg (Photo by

Gernot Wagner in Bloomberg (Photo by