by Fabio Tollon

Are we responsible for the future? In some very basic sense of responsibility we are: what we do now will have a causal effect on things that happen later. However, such causal responsibility is not always enough to establish whether or not we have certain obligations towards the future. Be that as it may, there are still instances where we do have such obligations. For example, our failure to adequately address the causes of climate change (us) will ultimately lead to future generations having to suffer. An important question to consider is whether we ought to bear some moral responsibility for future states of affairs (known as forward-looking, or prospective, responsibility). In the case of climate change, it does seem as though we have a moral obligation to do something, and that should we fail, we are on the hook. One significant reason for this is that we can foresee that our actions (or inactions) now will lead to certain desirable or undesirable consequences. When we try and apply this way of thinking about prospective responsibility to AI, however, we might run into some trouble.

AI-driven systems are often by their very nature unpredictable, meaning that engineers and designers cannot reliably foresee what might occur once the system is deployed. Consider the case of machine learning systems which discover novel correlations in data. In such cases, the programmers cannot predict what results the system will spit out. The entire purpose of using the system is so that it can uncover correlations that are in some cases impossible to see with only human cognitive powers. Thus, the threat seems to come from the fact that we lack a reliable way to anticipate the consequences of AI, which perhaps make us being responsible for it, in a forward-looking sense, impossible.

Essentially, the innovative and experimental nature of AI research and development may undermine the relevant control required for reasonable ascriptions of forward-looking responsibility. However, as I hope to show, when we reflect on technological assessment more generally, we may come to see that just because we cannot predict future consequences does not necessary mean there is a “gap” in forward looking obligation. Read more »

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer. In Call Me Ishmael, Charles Olson’s magnificent 1947 study of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, the American poet writes: “I take SPACE to be the central fact to man born in America.” Using a common alternative title for the 1851 novel, Olson compares it to Walt Whitman’s self-published paean to his country: “The White Whale is more accurate than Leaves of Grass. Because it is America, all of her space, the malice, the root.”

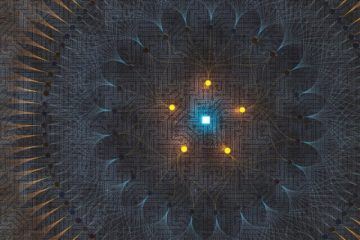

In Call Me Ishmael, Charles Olson’s magnificent 1947 study of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, the American poet writes: “I take SPACE to be the central fact to man born in America.” Using a common alternative title for the 1851 novel, Olson compares it to Walt Whitman’s self-published paean to his country: “The White Whale is more accurate than Leaves of Grass. Because it is America, all of her space, the malice, the root.” Quantum physicist Mario Krenn remembers sitting in a café in Vienna in early 2016, poring over computer printouts, trying to make sense of what MELVIN had found. MELVIN was a machine-learning algorithm Krenn had built, a kind of artificial intelligence. Its job was to mix and match the building blocks of standard quantum experiments and find solutions to new problems. And it did find many interesting ones. But there was one that made no sense.

Quantum physicist Mario Krenn remembers sitting in a café in Vienna in early 2016, poring over computer printouts, trying to make sense of what MELVIN had found. MELVIN was a machine-learning algorithm Krenn had built, a kind of artificial intelligence. Its job was to mix and match the building blocks of standard quantum experiments and find solutions to new problems. And it did find many interesting ones. But there was one that made no sense.

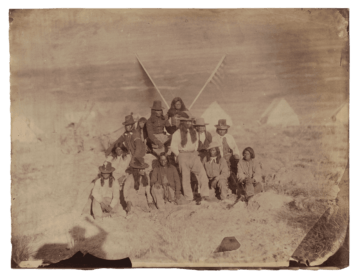

In September 1793, British envoy Lord Macartney was given a tour of the Qing summer palace north of Beijing. Earlier in his trip he presented the Qianlong emperor with gifts of two enameled watches of “very fine workmanship,” a telescope, Birmingham sword blades, and fine British clothes, among other items meant to awe the aging monarch with the superiority of British technology and manufacturing and convince him to sign a trade agreement.

In September 1793, British envoy Lord Macartney was given a tour of the Qing summer palace north of Beijing. Earlier in his trip he presented the Qianlong emperor with gifts of two enameled watches of “very fine workmanship,” a telescope, Birmingham sword blades, and fine British clothes, among other items meant to awe the aging monarch with the superiority of British technology and manufacturing and convince him to sign a trade agreement. My daughter recently remarked, over breakfast in a cafe, that the customers, rather than the serving staff, should be known as waiters. Then she removed the mantle of cheese from my side order of hash browns and pointed out that these too were poorly named, since they were actually a shade of yellow. She is 3 years old—and though the assertive mode mostly trumps the interrogative, lately she has started asking tough questions about the English language.

My daughter recently remarked, over breakfast in a cafe, that the customers, rather than the serving staff, should be known as waiters. Then she removed the mantle of cheese from my side order of hash browns and pointed out that these too were poorly named, since they were actually a shade of yellow. She is 3 years old—and though the assertive mode mostly trumps the interrogative, lately she has started asking tough questions about the English language. Readers of “Through the Looking-Glass” may recall the plight of the Bread-and-Butterfly, which, as the Gnat explains to Alice, can live only on weak tea with cream in it. “Supposing it couldn’t find any?” Alice asks. “Then it would die, of course,” the Gnat answers. “That must happen very often,” Alice reflects. “It always happens,” the Gnat admits, dolefully.

Readers of “Through the Looking-Glass” may recall the plight of the Bread-and-Butterfly, which, as the Gnat explains to Alice, can live only on weak tea with cream in it. “Supposing it couldn’t find any?” Alice asks. “Then it would die, of course,” the Gnat answers. “That must happen very often,” Alice reflects. “It always happens,” the Gnat admits, dolefully. Lorna Finlayson in Sidecar:

Lorna Finlayson in Sidecar: Macabe Keliher in Boston Review:

Macabe Keliher in Boston Review: Ho-fung Hung in Phenomenal World:

Ho-fung Hung in Phenomenal World: DENIS JOHNSON UNDERSTOOD the impulse to check out. He understood a lot of things, including the contradictory nature of truth. He himself was the son of a US State Department employee stationed overseas, a well-to-do suburban American boy who was “saved” from the penitentiary, as he put it, by “the Beatnik category.” He went to college, published a book of poetry by the age of nineteen (The Man Among the Seals), went to graduate school and got an MFA, but was also an alkie drifter and heroin addict: a “real” writer, in other words (who, like any really real writer, can’t be pigeonholed by one coherent myth, or by trite ideas about the school of life). Later he got clean and became some kind of Christian, published many novels and a book of outstanding essays (Seek), lived in remote northern Idaho but traveled and wrote into multiple zones of conflict—Somalia, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan, and famously, in Tree of Smoke, wartime Vietnam. Perhaps being raised abroad, in various far-flung locations (Germany, the Philippines, and Japan), gave him a better feeling for the lost and ugly American, the juncture of the epic and pathetic, the suicidal tendencies of the everyday joe, which seem to have been his wellspring.

DENIS JOHNSON UNDERSTOOD the impulse to check out. He understood a lot of things, including the contradictory nature of truth. He himself was the son of a US State Department employee stationed overseas, a well-to-do suburban American boy who was “saved” from the penitentiary, as he put it, by “the Beatnik category.” He went to college, published a book of poetry by the age of nineteen (The Man Among the Seals), went to graduate school and got an MFA, but was also an alkie drifter and heroin addict: a “real” writer, in other words (who, like any really real writer, can’t be pigeonholed by one coherent myth, or by trite ideas about the school of life). Later he got clean and became some kind of Christian, published many novels and a book of outstanding essays (Seek), lived in remote northern Idaho but traveled and wrote into multiple zones of conflict—Somalia, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan, and famously, in Tree of Smoke, wartime Vietnam. Perhaps being raised abroad, in various far-flung locations (Germany, the Philippines, and Japan), gave him a better feeling for the lost and ugly American, the juncture of the epic and pathetic, the suicidal tendencies of the everyday joe, which seem to have been his wellspring.