Elham Saeidinezhad over at his website:

Elham Saeidinezhad over at his website:

Who has access to cheap credit? And who does not? Compared to small businesses and households, global banks disproportionately benefited from the Fed’s liquidity provision measures. Yet, this distributional issue at the heart of the liquidity provision programs is excluded from analyzing the recession-fighting measures’ distributional footprints. After the great financial crisis (GFC) and the Covid-19 pandemic, the Fed’s focus has been on the asset purchasing programs and their impacts on the “real variables” such as wealth. The concern has been whether the asset-purchasing measures have benefited the wealthy disproportionately by boosting asset prices. Yet, the Fed seems unconcerned about the unequal distribution of cheap credits and the impacts of its “liquidity facilities.” Such oversight is paradoxical. On the one hand, the Fed is increasing its effort to tackle the rising inequality resulting from its unconventional schemes. On the other hand, its liquidity facilities are being directed towards shadow banking rather than short-term consumers loans. A concerned Fed about inequality should monitor the distributional footprints of their policies on access to cheap debt rather than wealth accumulation.

Dismissing the effects of unequal access to cheap credit on inequality is not an intellectual mishap. Instead, it has its root in an old idea in monetary economics- the quantity theory of money– that asserts money is neutral. According to monetary neutrality, money, and credit, that cover the daily cash-flow commitments are veils. In search of the “veil of money,” the quantity theory takes two necessary steps: first, it disregards the payment systems as mere plumbing behind the transactions in the real economy.

More here.

On the night of August 20, 1968, neighbors woke the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal and his wife, Eliška Plevová, to tell them that the Soviet Union was invading. Already their occupiers, the Soviets were now coming to put an end to the reforms of the Prague Spring. By morning, planes were flying low overhead, and soldiers and tanks filled the streets. One tank pointed its cannon directly at the offices of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers in Wenceslas Square. Hrabal, however, was eager to fulfill his duties as the best man at the wedding of his friend, the graphic artist Vladimír Boudník, in nearby Český Krumlov. “I set out in my car,” Hrabal writes in The Gentle Barbarian, “but I couldn’t get out of Prague, either through the city centre, or by using back routes, because the fraternal armies had arrived to liquidate something that was not there.” So he returned home, tried to attend a gallery show on modern American art (sorry, closed), and later relayed his troubles to his and Boudník’s mutual friend, the writer and philosopher Egon Bondy. Bondy, who called Hrabal by his nickname, Doctor, explodes in a frenzy of jealousy and admiration for Boudník:

On the night of August 20, 1968, neighbors woke the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal and his wife, Eliška Plevová, to tell them that the Soviet Union was invading. Already their occupiers, the Soviets were now coming to put an end to the reforms of the Prague Spring. By morning, planes were flying low overhead, and soldiers and tanks filled the streets. One tank pointed its cannon directly at the offices of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers in Wenceslas Square. Hrabal, however, was eager to fulfill his duties as the best man at the wedding of his friend, the graphic artist Vladimír Boudník, in nearby Český Krumlov. “I set out in my car,” Hrabal writes in The Gentle Barbarian, “but I couldn’t get out of Prague, either through the city centre, or by using back routes, because the fraternal armies had arrived to liquidate something that was not there.” So he returned home, tried to attend a gallery show on modern American art (sorry, closed), and later relayed his troubles to his and Boudník’s mutual friend, the writer and philosopher Egon Bondy. Bondy, who called Hrabal by his nickname, Doctor, explodes in a frenzy of jealousy and admiration for Boudník: Gideon Jones in Strife:

Gideon Jones in Strife: Robert Hockett in Forbes:

Robert Hockett in Forbes: T

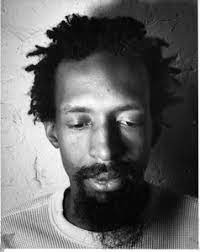

T Eastman died in 1990, at the age of forty-nine. Ebullient and confrontational in equal measure, he attended the Curtis Institute of Music, joined the Creative Associates program at the University of Buffalo, and found a degree of renown in avant-garde circles. In his final years, struggling with addiction, he faded from view. As a Black gay man, he encountered resistance and incomprehension during his lifetime. He is now experiencing a dizzying posthumous renaissance, to the point where his Symphony No. II is scheduled for the New York Philharmonic’s 2021-22 season.

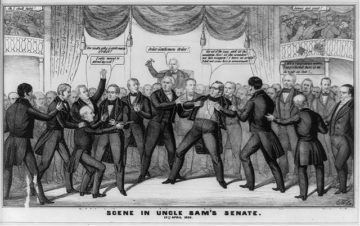

Eastman died in 1990, at the age of forty-nine. Ebullient and confrontational in equal measure, he attended the Curtis Institute of Music, joined the Creative Associates program at the University of Buffalo, and found a degree of renown in avant-garde circles. In his final years, struggling with addiction, he faded from view. As a Black gay man, he encountered resistance and incomprehension during his lifetime. He is now experiencing a dizzying posthumous renaissance, to the point where his Symphony No. II is scheduled for the New York Philharmonic’s 2021-22 season. The United States is not in the midst of a “culture war” over race and racism. The animating force of our current conflict is not our differing values, beliefs, moral codes, or practices. The American people aren’t divided. The American people are being divided. Republican operatives have

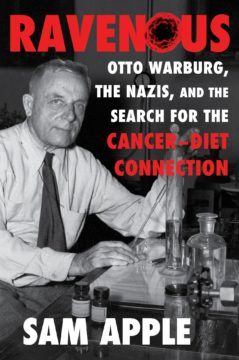

The United States is not in the midst of a “culture war” over race and racism. The animating force of our current conflict is not our differing values, beliefs, moral codes, or practices. The American people aren’t divided. The American people are being divided. Republican operatives have  When the Nazis seized power in March 1933, it was not unusual for major scientific institutes to be led by Nobel laureates with Jewish roots: Albert Einstein and Otto Meyerhof, both Jewish, ran prestigious centers of physics and medical research; Fritz Haber, who’d converted from Judaism in the late 19th century, ran a chemistry institute; and Otto Warburg, who was raised as a Protestant but had two Jewish grandparents, was the director of a recently opened center for cell physiology.

When the Nazis seized power in March 1933, it was not unusual for major scientific institutes to be led by Nobel laureates with Jewish roots: Albert Einstein and Otto Meyerhof, both Jewish, ran prestigious centers of physics and medical research; Fritz Haber, who’d converted from Judaism in the late 19th century, ran a chemistry institute; and Otto Warburg, who was raised as a Protestant but had two Jewish grandparents, was the director of a recently opened center for cell physiology. When critics write at length about the critics they admire, look out for self-portraiture. In a 2008 New Yorker essay, the critic and intellectual historian Louis Menand explored Lionel Trilling’s influence on the postwar era, during which Trilling was America’s preeminent literary critic and among its weightiest public intellectuals. One of the few aspects of Trilling’s career about which Menand had major reservations was the unfinished second novel Trilling began shortly after publishing his first, The Middle of the Journey, but abandoned about a third of the way through. This work, Menand found, “doesn’t have much literary interest, but it does have a lot of biographical interest, because it lets us see Trilling imagining his own world—the world of ambitious young critics, resentful middle-aged professors, pompous publishers and compromised foundation heads, intellectual femmes fatales, and the megalomaniacal editors of little magazines—as a nineteenth-century novel.”

When critics write at length about the critics they admire, look out for self-portraiture. In a 2008 New Yorker essay, the critic and intellectual historian Louis Menand explored Lionel Trilling’s influence on the postwar era, during which Trilling was America’s preeminent literary critic and among its weightiest public intellectuals. One of the few aspects of Trilling’s career about which Menand had major reservations was the unfinished second novel Trilling began shortly after publishing his first, The Middle of the Journey, but abandoned about a third of the way through. This work, Menand found, “doesn’t have much literary interest, but it does have a lot of biographical interest, because it lets us see Trilling imagining his own world—the world of ambitious young critics, resentful middle-aged professors, pompous publishers and compromised foundation heads, intellectual femmes fatales, and the megalomaniacal editors of little magazines—as a nineteenth-century novel.” Einstein completed his Ph.D. thesis in 1905 with Professor

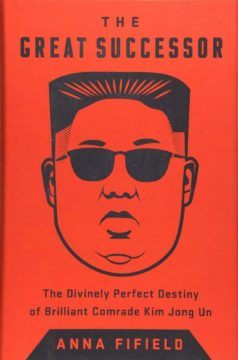

Einstein completed his Ph.D. thesis in 1905 with Professor  Not too many 38-years-olds deserve their own biography, let alone two. But ever since Kim Jong Un became the third ruler of North Korea in 2011, he has fascinated the American media. A Seth Rogen movie, The New Yorker covers, and South Park cartoons have all made Kim — and his haircut — the target of much lampooning. And in one of the strangest twists in recent international diplomacy, Donald Trump caused a sensation by announcing the two “fell in love” with each other. All this publicity has ultimately resulted in a cartoonish version of Kim, which, however good for a chuckle, obscures how this enigmatic dictator and his family have ruled over the course of three generations.

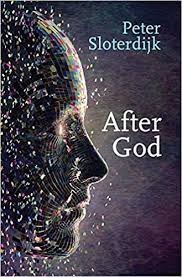

Not too many 38-years-olds deserve their own biography, let alone two. But ever since Kim Jong Un became the third ruler of North Korea in 2011, he has fascinated the American media. A Seth Rogen movie, The New Yorker covers, and South Park cartoons have all made Kim — and his haircut — the target of much lampooning. And in one of the strangest twists in recent international diplomacy, Donald Trump caused a sensation by announcing the two “fell in love” with each other. All this publicity has ultimately resulted in a cartoonish version of Kim, which, however good for a chuckle, obscures how this enigmatic dictator and his family have ruled over the course of three generations. There is also a kind of ostentatious world-weariness in his writings that can be oddly enchanting. In one sense, his thought is burdened by that deep historical consciousness that seems to be the peculiar vocation of continental philosophy in its long post-Hegelian twilight. As a result, he possesses too keen a hermeneutical awareness of the fluidity, ambiguity, and cultural contingency of philosophy’s terms and concepts to mistake them for invariable properties that can be absorbed into some timeless propositional calculus in the way so much of Anglo-American philosophy imagines it can. But, in another sense, it is precisely this “burden” of historical consciousness that imparts a paradoxical levity to his project. Many of his books feel like expeditions in search of secrets from the past: forgotten cultural ancestries, effaced spiritual monuments, occult currents within the flow of social evolution. Whether one admires or deplores his thought—or has a distinctly mixed opinion of it, as I do—no one could plausibly claim that it is dull.

There is also a kind of ostentatious world-weariness in his writings that can be oddly enchanting. In one sense, his thought is burdened by that deep historical consciousness that seems to be the peculiar vocation of continental philosophy in its long post-Hegelian twilight. As a result, he possesses too keen a hermeneutical awareness of the fluidity, ambiguity, and cultural contingency of philosophy’s terms and concepts to mistake them for invariable properties that can be absorbed into some timeless propositional calculus in the way so much of Anglo-American philosophy imagines it can. But, in another sense, it is precisely this “burden” of historical consciousness that imparts a paradoxical levity to his project. Many of his books feel like expeditions in search of secrets from the past: forgotten cultural ancestries, effaced spiritual monuments, occult currents within the flow of social evolution. Whether one admires or deplores his thought—or has a distinctly mixed opinion of it, as I do—no one could plausibly claim that it is dull. Weil’s essential contribution to the theory of complaint comes by way of her distinction between ordinary suffering and something she calls “affliction.” Suffering is pain one can bear, pain that does not imprint itself on the soul. Sometimes, we even choose suffering, as in strenuous exercise, unmedicated childbirth or getting one’s ears pierced. Getting beat up in an alleyway by strangers is not like any of those forms of suffering. A violent attack, even one that does minimum physical damage, hurts in a distinctive way—in a way that, as Weil would put it, raises a question.

Weil’s essential contribution to the theory of complaint comes by way of her distinction between ordinary suffering and something she calls “affliction.” Suffering is pain one can bear, pain that does not imprint itself on the soul. Sometimes, we even choose suffering, as in strenuous exercise, unmedicated childbirth or getting one’s ears pierced. Getting beat up in an alleyway by strangers is not like any of those forms of suffering. A violent attack, even one that does minimum physical damage, hurts in a distinctive way—in a way that, as Weil would put it, raises a question. The duration of felt experience is between two and three seconds—about as long as it takes, the psychologist Marc Wittmann points out, for Paul McCartney to sing the words “Hey Jude.” Everything before belongs to memory; everything after is anticipation. It’s a strange, barely fathomable fact that our lives are lived through this small, moving window. Practitioners of mindfulness meditation often strive to rest their consciousness within it. The rest of us might encounter something similar during certain present-tense moments—perhaps while rock climbing, improvising music, making love. Being in the moment is said to be a perk of sadomasochism; as a devotee of B.D.S.M. once explained, “A whip is a great way to get someone to be here now. They can’t look away from it, and they can’t think about anything else!”

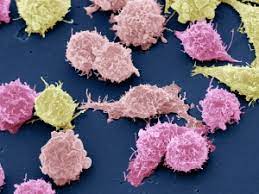

The duration of felt experience is between two and three seconds—about as long as it takes, the psychologist Marc Wittmann points out, for Paul McCartney to sing the words “Hey Jude.” Everything before belongs to memory; everything after is anticipation. It’s a strange, barely fathomable fact that our lives are lived through this small, moving window. Practitioners of mindfulness meditation often strive to rest their consciousness within it. The rest of us might encounter something similar during certain present-tense moments—perhaps while rock climbing, improvising music, making love. Being in the moment is said to be a perk of sadomasochism; as a devotee of B.D.S.M. once explained, “A whip is a great way to get someone to be here now. They can’t look away from it, and they can’t think about anything else!” Two compendiums of data unite genetic profiling with drug testing to create the most complete picture yet of how mutations can shape a cancer’s response to therapy. The results, published today in Nature

Two compendiums of data unite genetic profiling with drug testing to create the most complete picture yet of how mutations can shape a cancer’s response to therapy. The results, published today in Nature