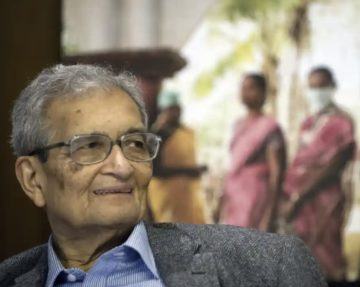

Abhrajyoti Chakraborty in The Guardian:

Amartya Sen was 18 when he diagnosed his own cancer. Not long after he had moved to Calcutta for college, he noticed a lump growing inside his mouth. He consulted two doctors but they laughed away his suspicions, so Sen, then a student of economics and mathematics, looked up a couple of books on cancer from a medical library. He identified the tumour – a “squamous cell carcinoma” – and later when a biopsy confirmed his verdict he wondered if there were in effect two people with his name: a patient who had just been told he had cancer, but also the “agent” responsible for the diagnosis. “I must not let the agent in me go away,” Sen decided, “and could not – absolutely could not – let the patient take over completely.”

Amartya Sen was 18 when he diagnosed his own cancer. Not long after he had moved to Calcutta for college, he noticed a lump growing inside his mouth. He consulted two doctors but they laughed away his suspicions, so Sen, then a student of economics and mathematics, looked up a couple of books on cancer from a medical library. He identified the tumour – a “squamous cell carcinoma” – and later when a biopsy confirmed his verdict he wondered if there were in effect two people with his name: a patient who had just been told he had cancer, but also the “agent” responsible for the diagnosis. “I must not let the agent in me go away,” Sen decided, “and could not – absolutely could not – let the patient take over completely.”

This self-division is characteristic of Home in the World – “world” being here no more than the university campuses Sen has lived in all his life – and places it in the tradition of CLR James’s Beyond a Boundary and Nirad C Chaudhuri’s The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian: books that, in their primacy of thought over feeling, reflect the psychic extent of the colonial encounter. The empire loomed early in Sen’s life, though he was born and schooled in Santiniketan, the idyllic campus set up by the poet Rabindranath Tagore in rural Bengal.

More here.

Fifteen months after the novel coronavirus shut down much of the world, the pandemic is still raging. Few experts guessed that by this point, the world would have not one vaccine but many, with 3 billion doses already delivered. At the same time, the coronavirus has evolved into super-transmissible variants that spread more easily. The clash between these variables will define the coming months and seasons. Here, then, are three simple principles to understand how they interact. Each has caveats and nuances, but together, they can serve as a guide to our near-term future.

Fifteen months after the novel coronavirus shut down much of the world, the pandemic is still raging. Few experts guessed that by this point, the world would have not one vaccine but many, with 3 billion doses already delivered. At the same time, the coronavirus has evolved into super-transmissible variants that spread more easily. The clash between these variables will define the coming months and seasons. Here, then, are three simple principles to understand how they interact. Each has caveats and nuances, but together, they can serve as a guide to our near-term future. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will trumpet its own version of history as it celebrates its centenary on Thursday, and remind its citizens and the world of its centrality to China’s lofty economic and global aspirations in the decades ahead. It rules with a swagger about its accomplishments and a grand narrative about the future, and yet also with a repression and prickliness that are more consistent with a state of siege. China’s party leaders still fret about what happened to their Soviet counterparts and are determined to avoid a similar fate. China’s Leninist party has fared much better, but it nevertheless has good reason to be wary that the 2020s will be an important acid test.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will trumpet its own version of history as it celebrates its centenary on Thursday, and remind its citizens and the world of its centrality to China’s lofty economic and global aspirations in the decades ahead. It rules with a swagger about its accomplishments and a grand narrative about the future, and yet also with a repression and prickliness that are more consistent with a state of siege. China’s party leaders still fret about what happened to their Soviet counterparts and are determined to avoid a similar fate. China’s Leninist party has fared much better, but it nevertheless has good reason to be wary that the 2020s will be an important acid test.

For 27 July 1794, ‘9 Thermidor Year II’ in the new republican calendar, has long been recognised as a ‘pivotal moment’ in the French Revolution. Until that point, the course of the revolution had been marked by increasing radicalism: France had gone from constitutional monarchy after the fall of the Bastille in 1789, to kingless republic in 1792, to wartime police state from 1793. After the events of 9 Thermidor, the trend was towards increasing conservatism. The democratic and reformist energies of the early revolution were mostly dissipated. Within a decade, France was again a monarchy, with a Corsican-born emperor in place of a Bourbon king.

For 27 July 1794, ‘9 Thermidor Year II’ in the new republican calendar, has long been recognised as a ‘pivotal moment’ in the French Revolution. Until that point, the course of the revolution had been marked by increasing radicalism: France had gone from constitutional monarchy after the fall of the Bastille in 1789, to kingless republic in 1792, to wartime police state from 1793. After the events of 9 Thermidor, the trend was towards increasing conservatism. The democratic and reformist energies of the early revolution were mostly dissipated. Within a decade, France was again a monarchy, with a Corsican-born emperor in place of a Bourbon king. I spent many years thinking about how to design an imaging study that could identify the unique features of the creative brain. Most of the human brain’s functions arise from the 6 layers of nerve cells and their dendrites embedded in its enormous surface area, called the cerebral cortex — which is compressed to a size small enough to be carried around on our shoulders through a process known as gyrification — essentially, producing lots of folds.

I spent many years thinking about how to design an imaging study that could identify the unique features of the creative brain. Most of the human brain’s functions arise from the 6 layers of nerve cells and their dendrites embedded in its enormous surface area, called the cerebral cortex — which is compressed to a size small enough to be carried around on our shoulders through a process known as gyrification — essentially, producing lots of folds. IMPLEMENTATION of the PTI’s Single National Curriculum has started in Islamabad’s schools and for students the human body is to become a dark mystery, darker than ever before. Religious scholars appointed as members of the SNC Committee are

IMPLEMENTATION of the PTI’s Single National Curriculum has started in Islamabad’s schools and for students the human body is to become a dark mystery, darker than ever before. Religious scholars appointed as members of the SNC Committee are  Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable.

Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable. A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.