Hasan Altaf in The Paris Review:

After her first novel, The God of Small Things (1997), Arundhati Roy did not publish another for twenty years, when The Ministry of Utmost Happiness was released in 2017. The intervening decades were nonetheless filled with writing: essays on dams, displacement, and democracy, which appeared in newspapers and magazines such as Outlook, Frontline, and the Guardian, and were collected in volumes that quickly came to outnumber the novels. Most of these essays were compiled in 2019 in My Seditious Heart, which, with footnotes, comes to nearly a thousand pages; less than a year later she published nine new essays in Azadi.

After her first novel, The God of Small Things (1997), Arundhati Roy did not publish another for twenty years, when The Ministry of Utmost Happiness was released in 2017. The intervening decades were nonetheless filled with writing: essays on dams, displacement, and democracy, which appeared in newspapers and magazines such as Outlook, Frontline, and the Guardian, and were collected in volumes that quickly came to outnumber the novels. Most of these essays were compiled in 2019 in My Seditious Heart, which, with footnotes, comes to nearly a thousand pages; less than a year later she published nine new essays in Azadi.

To see that two-decade period as a gap, or the nonfiction as separate from the fiction, would be to misunderstand Roy’s project; when finding herself described as “what is known in twenty-first-century vernacular as a ‘writer-activist,’ ” she confessed that term made her flinch (and feel “like a sofa-bed”). The essays exist between the novels not as a wall but as a bridge. Roy’s subject and obsession is, throughout, power: who has it (and why), how it is used (and abused), the ways in which those with little power turn on those with less—and, importantly, how to find beauty and joy amid these struggles.

More here.

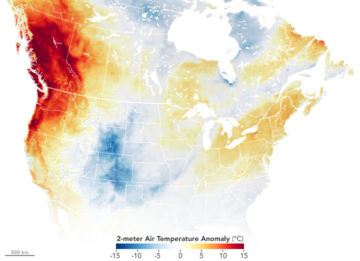

The last week of June saw shocking temperatures in Oregon, Washington state, and British Columbia. Differentiating a forecast in Canada from a forecast in Phoenix is usually a breeze, but not in June. All-time high-temperature records—not just daily records—were smashed across the region. Portland International Airport broke its all-time record of 41.7°C (107°F) by a whopping 5°C (9°F). The small town of Lytton set a new record high for the entire country of Canada at 49.6°C (121.3°F) on June 29. In the days that followed,

The last week of June saw shocking temperatures in Oregon, Washington state, and British Columbia. Differentiating a forecast in Canada from a forecast in Phoenix is usually a breeze, but not in June. All-time high-temperature records—not just daily records—were smashed across the region. Portland International Airport broke its all-time record of 41.7°C (107°F) by a whopping 5°C (9°F). The small town of Lytton set a new record high for the entire country of Canada at 49.6°C (121.3°F) on June 29. In the days that followed,  This is how capitalism ends: not with a revolutionary bang, but with an evolutionary whimper. Just as it displaced feudalism gradually, surreptitiously, until one day the bulk of human relations were market-based and feudalism was swept away, so capitalism today is being toppled by a new economic mode: techno-feudalism.

This is how capitalism ends: not with a revolutionary bang, but with an evolutionary whimper. Just as it displaced feudalism gradually, surreptitiously, until one day the bulk of human relations were market-based and feudalism was swept away, so capitalism today is being toppled by a new economic mode: techno-feudalism. Taja Cheek is walking through time. Facing the bustling intersection of Saint Marks and Nostrand Avenues in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, she points towards the former location of the Continental jazz club, which her grandfather owned in the 1950s. It’s walking distance from the apartment where Cheek has lived for the better part of a decade, and where she once booked her own basement shows, featuring the likes of TV on the Radio’s Kyp Malone and NYC noise fixture Dreamcrusher. And it’s not far from where Cheek grew up further down Eastern Parkway, practicing Debussy on piano when she wasn’t taking in the city’s sounds—jazz on the radio, Carribean music on the streets, and ’90s rap and R&B in the air. “That’s such a big part of the music I know and that matters to me: the music I absorbed just from being around it,” she says. “I have all these memories of playing Double Dutch on the street and hearing music playing from cars.”

Taja Cheek is walking through time. Facing the bustling intersection of Saint Marks and Nostrand Avenues in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, she points towards the former location of the Continental jazz club, which her grandfather owned in the 1950s. It’s walking distance from the apartment where Cheek has lived for the better part of a decade, and where she once booked her own basement shows, featuring the likes of TV on the Radio’s Kyp Malone and NYC noise fixture Dreamcrusher. And it’s not far from where Cheek grew up further down Eastern Parkway, practicing Debussy on piano when she wasn’t taking in the city’s sounds—jazz on the radio, Carribean music on the streets, and ’90s rap and R&B in the air. “That’s such a big part of the music I know and that matters to me: the music I absorbed just from being around it,” she says. “I have all these memories of playing Double Dutch on the street and hearing music playing from cars.” This is just the most egregious example of what the Financial Times’s chief features writer, Henry Mance, describes as ‘the meat paradox’: a state of affairs where ‘people who care about animals manage not to care about farm animals’. It’s not just omnivores who are in denial. Vegetarians are arguably just as self-deceived. The life of a typical dairy cow is worse than that of one destined to end up as steaks. In the United States, up to half of dairy cows suffer lameness, a problem also rife in the United Kingdom. Vegetarians can’t even claim that at least they are not responsible for the slaughter of cows, since the economics of the dairy industry means that most male calves are killed at birth, once they have served their only purpose as catalysts of lactation. ‘If you are really concerned about animal welfare,’ says Mance, ‘you should almost certainly stop eating dairy before you stop eating beef.’

This is just the most egregious example of what the Financial Times’s chief features writer, Henry Mance, describes as ‘the meat paradox’: a state of affairs where ‘people who care about animals manage not to care about farm animals’. It’s not just omnivores who are in denial. Vegetarians are arguably just as self-deceived. The life of a typical dairy cow is worse than that of one destined to end up as steaks. In the United States, up to half of dairy cows suffer lameness, a problem also rife in the United Kingdom. Vegetarians can’t even claim that at least they are not responsible for the slaughter of cows, since the economics of the dairy industry means that most male calves are killed at birth, once they have served their only purpose as catalysts of lactation. ‘If you are really concerned about animal welfare,’ says Mance, ‘you should almost certainly stop eating dairy before you stop eating beef.’ T

T In “All Eyes on Me,” a song from his new Netflix special Inside, the musician-comedian Bo Burnham pauses to ask, “You want to hear a funny story?” He tells us that, five years ago, he quit performing live because, while on stage, he’d experience severe panic attacks. He spent that time trying to improve himself mentally instead. “And you know what? I did,” Burnham says. He got better. “So much better, in fact, that in January of 2020, I thought, ‘You know what, I should start performing again.’” He’d been a kind of recluse. It was time to rectify that, he says. “And then, the funniest thing happened…”

In “All Eyes on Me,” a song from his new Netflix special Inside, the musician-comedian Bo Burnham pauses to ask, “You want to hear a funny story?” He tells us that, five years ago, he quit performing live because, while on stage, he’d experience severe panic attacks. He spent that time trying to improve himself mentally instead. “And you know what? I did,” Burnham says. He got better. “So much better, in fact, that in January of 2020, I thought, ‘You know what, I should start performing again.’” He’d been a kind of recluse. It was time to rectify that, he says. “And then, the funniest thing happened…” The painting is known as Woman in Grey Reclining. It was painted in 1879. It depicts a woman in a lovely dress reclining on a couch. Does she have a white flower on the left strap of her dress? Maybe. Probably. We cannot be completely sure. That’s because much of the detail in the painting is only hinted at by the brushwork. A few dabs of white paint here. A few daubs of grey over there. A stroke of black across the neck, giving us the sense of a choker. We’ve come to call this kind of painting impressionist. The term was originally meant as an insult. But it stuck and became a moniker of pride, as often happens with insults.

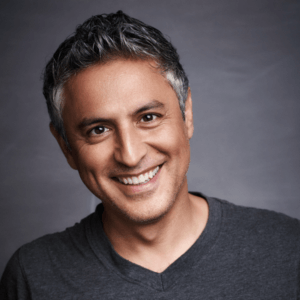

The painting is known as Woman in Grey Reclining. It was painted in 1879. It depicts a woman in a lovely dress reclining on a couch. Does she have a white flower on the left strap of her dress? Maybe. Probably. We cannot be completely sure. That’s because much of the detail in the painting is only hinted at by the brushwork. A few dabs of white paint here. A few daubs of grey over there. A stroke of black across the neck, giving us the sense of a choker. We’ve come to call this kind of painting impressionist. The term was originally meant as an insult. But it stuck and became a moniker of pride, as often happens with insults. Religion is an important part of the lives of billions of people around the world, but what religious belief actually amounts to can vary considerably from person to person. Some believe in an anthropomorphic, judgmental God; others conceive of God as more transcendent and conceptual; some are animists who attribute spiritual essence to creatures and objects; and many more. I talk with writer and religious scholar Reza Aslan about his view of religion as a vocabulary constructed by human beings to express a connection with something beyond the physical world — why one might think that, and what it implies about how we should go about living our lives.

Religion is an important part of the lives of billions of people around the world, but what religious belief actually amounts to can vary considerably from person to person. Some believe in an anthropomorphic, judgmental God; others conceive of God as more transcendent and conceptual; some are animists who attribute spiritual essence to creatures and objects; and many more. I talk with writer and religious scholar Reza Aslan about his view of religion as a vocabulary constructed by human beings to express a connection with something beyond the physical world — why one might think that, and what it implies about how we should go about living our lives. I’m suburban; I’m of the suburbs. I’ve spent my entire adulthood in cities, but I still get nostalgic when I smell freshly cut grass. It brings me back to the malls of my youth, to the food court at Town Center at Boca Raton, the mall we used to go to whenever I visited my grandparents in South Florida, or the old tobacco store in some forgotten shopping center in the middle of the country. I love grilling meat on a Weber grill I spent an hour trying to light, and by God, I miss not having a never-ending stream of cars honking outside my window.

I’m suburban; I’m of the suburbs. I’ve spent my entire adulthood in cities, but I still get nostalgic when I smell freshly cut grass. It brings me back to the malls of my youth, to the food court at Town Center at Boca Raton, the mall we used to go to whenever I visited my grandparents in South Florida, or the old tobacco store in some forgotten shopping center in the middle of the country. I love grilling meat on a Weber grill I spent an hour trying to light, and by God, I miss not having a never-ending stream of cars honking outside my window. Burning Man, a new biography of Lawrence stuffed with fascinating research – his battleground of a childhood, his “raid” on literary London, life in Cornwall with Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry, lifelong denials of, and battles with, tuberculosis, referred to by him as “the bronchials”, his first meeting with Frieda von Richthofen, his “destiny” and life partner, fights between them, their penniless travels on foot, donkey and ferry throughout Europe, in Florence with Norman Douglas, the pilgrimage to New Mexico and Mabel Dodge, her quest to “save” the Pueblo Indians, his novels, poems and literary criticisms ‑ is wonderful in many ways; but here’s my caveat: can a new biography of Lawrence really ignore Kate Millet’s critique of his work, declaring him one of the subtlest propagators of sexist, patriarchal propaganda? Can his novels, seen by Millet as laying the groundwork for today’s pornography, really stand unquestioned?

Burning Man, a new biography of Lawrence stuffed with fascinating research – his battleground of a childhood, his “raid” on literary London, life in Cornwall with Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry, lifelong denials of, and battles with, tuberculosis, referred to by him as “the bronchials”, his first meeting with Frieda von Richthofen, his “destiny” and life partner, fights between them, their penniless travels on foot, donkey and ferry throughout Europe, in Florence with Norman Douglas, the pilgrimage to New Mexico and Mabel Dodge, her quest to “save” the Pueblo Indians, his novels, poems and literary criticisms ‑ is wonderful in many ways; but here’s my caveat: can a new biography of Lawrence really ignore Kate Millet’s critique of his work, declaring him one of the subtlest propagators of sexist, patriarchal propaganda? Can his novels, seen by Millet as laying the groundwork for today’s pornography, really stand unquestioned? It’s terrifying how optimistic that era’s pessimism now seems. In Adventures in Paradise’s view of the future, we’re all fucked, to be sure, but at least we get to go to Mars, hang out with sentient robots, expand, accelerate, etc. The last four decades seems to have brought something like a great lowering of expectations, which David Graeber described like so: “A timid, bureaucratic spirit suffuses every aspect of cultural life. It comes festooned in a language of creativity, initiative, and entrepreneurialism. But the language is meaningless. . . . The greatest and most powerful nation that has ever existed has spent the last decades telling its citizens they can no longer contemplate fantastic collective enterprises.” Graeber singled out scientists and politicians for their contracting imaginations, but the creative class isn’t exempt— just look at the extraordinary success of Marvel Studios, the company whose fizzling pyrotechnics and brand-management-disguised-as-entertainment are a shadow of the American comic-book tradition to which Gary Panter has added so much.

It’s terrifying how optimistic that era’s pessimism now seems. In Adventures in Paradise’s view of the future, we’re all fucked, to be sure, but at least we get to go to Mars, hang out with sentient robots, expand, accelerate, etc. The last four decades seems to have brought something like a great lowering of expectations, which David Graeber described like so: “A timid, bureaucratic spirit suffuses every aspect of cultural life. It comes festooned in a language of creativity, initiative, and entrepreneurialism. But the language is meaningless. . . . The greatest and most powerful nation that has ever existed has spent the last decades telling its citizens they can no longer contemplate fantastic collective enterprises.” Graeber singled out scientists and politicians for their contracting imaginations, but the creative class isn’t exempt— just look at the extraordinary success of Marvel Studios, the company whose fizzling pyrotechnics and brand-management-disguised-as-entertainment are a shadow of the American comic-book tradition to which Gary Panter has added so much. It is no coincidence that caffeine and the minute-hand on clocks arrived at around the same historical moment, the acclaimed food and nature writer Michael Pollan argues in his latest book, This is Your Mind on Plants. Both spread across Europe as labourers began leaving the fields, where work is organised around the sun, for the factories, where shift-workers could no longer adhere to their natural patterns of sleep and wakefulness. Would capitalism even have been possible without caffeine?

It is no coincidence that caffeine and the minute-hand on clocks arrived at around the same historical moment, the acclaimed food and nature writer Michael Pollan argues in his latest book, This is Your Mind on Plants. Both spread across Europe as labourers began leaving the fields, where work is organised around the sun, for the factories, where shift-workers could no longer adhere to their natural patterns of sleep and wakefulness. Would capitalism even have been possible without caffeine? Biologist Teruhiko Wakayama envisions that one day, humans could populate other planets and seed new civilizations with animal sperm and egg cells they bring from Earth. Expanding humanity’s footprint into deep space will necessitate that humans ship out “Noah’s Arks” of this genetic material, each batch of cells a delegate of Earth’s biodiversity.

Biologist Teruhiko Wakayama envisions that one day, humans could populate other planets and seed new civilizations with animal sperm and egg cells they bring from Earth. Expanding humanity’s footprint into deep space will necessitate that humans ship out “Noah’s Arks” of this genetic material, each batch of cells a delegate of Earth’s biodiversity.