Lorna Finlayson in Sidecar:

Lorna Finlayson in Sidecar:

Philosophy in the so-called ‘analytic’ tradition has a strange relationship with politics. Normally seen as originating with Frege, Moore, Russell and Wittgenstein in the early 20th century, analytic philosophy was originally concerned with using formal logic to clarify and resolve fundamental metaphysical questions. Politics was largely ignored, according to the Oxford analyst Anthony Quinton, before the late 1960s. Political philosophy, in fact, was routinely pronounced ‘dead’ at the hands of the analysts – so dead that the tepid output of John Rawls (whose A Theory of Justice was published in 1971) could appear as a revival.

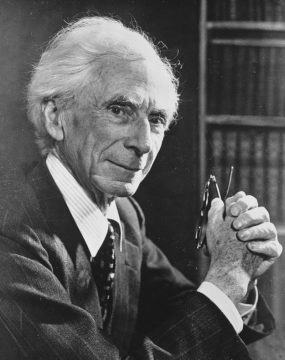

At the same time, analytic philosophers were not uninterested in politics. Bertrand Russell is an especially well-known case, but other figures such as A. J. Ayer and Stuart Hampshire – both supporters of the Labour Party (and in Ayer’s case, later the Social Democratic Party) and critics of the Vietnam War – were also politically involved. The reluctance to engage with politics in their professional capacities might seem thus to reflect not lack of political interest, but a view of philosophy as a largely separate sphere. Russell, for example, wrote that his ‘technical activities must be forgotten’ in order for his popular political writings to be properly understood, while Hampshire argued that although analytic philosophers ‘might happen to have political interests, […] their philosophical arguments were largely neutral politically.’

While at times insistent on the detachment of their philosophy from politics – stretching to a pride in the ‘conspicuous triviality’ of their own activity that the critic of ‘ordinary language philosophy’ Ernest Gellner saw as requiring the explanation of social historians – the analysts at other times floated some quite strong claims as to the political value and potential of their own ways of doing things.

More here.