Ian Frazier in The New Yorker:

Janet Malcolm, who wrote for this magazine for fifty-eight years, died this week in New York City, just a half mile or so from the building on East Seventy-second Street where she spent most of her childhood. Her family came from Prague in 1939, when she was almost five and her sister, Marie, was two and a half. Starting kindergarten with very little English, she had to guess at what was going on; every day, at the end of class, the teacher would say, “Goodbye, children.” She knew what “goodbye” meant but thought “children” must be the name of one of her classmates, and she hoped that one day the teacher would choose her, and say, “Goodbye, Janet.” Her father, Joseph, who changed his name from Wiener to Winn, was a psychiatrist and a neurologist; she later described him as “the gentlest of men.” Joan, his wife, worked at Voice of America and other jobs and ran the house.

Janet Malcolm, who wrote for this magazine for fifty-eight years, died this week in New York City, just a half mile or so from the building on East Seventy-second Street where she spent most of her childhood. Her family came from Prague in 1939, when she was almost five and her sister, Marie, was two and a half. Starting kindergarten with very little English, she had to guess at what was going on; every day, at the end of class, the teacher would say, “Goodbye, children.” She knew what “goodbye” meant but thought “children” must be the name of one of her classmates, and she hoped that one day the teacher would choose her, and say, “Goodbye, Janet.” Her father, Joseph, who changed his name from Wiener to Winn, was a psychiatrist and a neurologist; she later described him as “the gentlest of men.” Joan, his wife, worked at Voice of America and other jobs and ran the house.

Janet acquired the language in no time, not knowing how she did it. For the rest of her life, she spoke in an un-showy New York accent, like a quieter, non-gangster Bogart. As a teen-ager, she sometimes fooled around with it, pulling out the stops on the vowels, going into full dems-and-dose mode, just to see people’s surprise—at this slim and elegant girl suddenly becoming as loud as a “Guys and Dolls” showstopper. She accepted her own brilliance as no big deal. The precision with which she saw the world must have kept the grownups on their toes. She went to the High School of Music & Art and then to the University of Michigan, where she edited Gargoyle, the college humor magazine. She appears at the top of its masthead as “Managing Editor: J. W. Malcolm.” She had married Donald Malcolm, a fellow U. of M. student two years older than she was. The magazine’s articles often ran without bylines. An anonymous piece in the “anti-arts issue” titled “The Bobsey Twins Meet Ezra Pound” shows equal familiarity with the girl-detective mystery genre and early modernist poetry. Like Chekhov, Janet started out writing humor.

More here.

The sclera of the eye is devoid of pigment, which is why humans can easily follow where counterparts are looking. Researchers have long believed this facilitates glance-based communication. A team of zoologists based at the University of Duisburg-Essen (UDE) and the Anthropological Institute in Zurich is now challenging this traditional view in a new study. The researchers looked at communicative behavior and eye color in apes and question the proposed connection between the two phenomena. The results have just been published in Scientific Reports.

The sclera of the eye is devoid of pigment, which is why humans can easily follow where counterparts are looking. Researchers have long believed this facilitates glance-based communication. A team of zoologists based at the University of Duisburg-Essen (UDE) and the Anthropological Institute in Zurich is now challenging this traditional view in a new study. The researchers looked at communicative behavior and eye color in apes and question the proposed connection between the two phenomena. The results have just been published in Scientific Reports.

On February 18, 2021, NASA landed Perseverance rover on the surface of Mars. Perseverance is the latest of some twenty probes that NASA has sent to bring back detailed information about our neighboring planet, beginning with the Mariner spacecraft fly-by in 1965, which took the first closeup photograph. Though blurry by today’s standards, those grainy images helped ignite widespread wonder and fantasy about space exploration, not long before Star Trek also debuted on television. By the 1970s, science-fiction storytelling was moving from the margins of pop-culture into the mainstream in film and television—and so followed generations of kids, like myself, who grew up expecting off-world adventurism and alien encounters almost as much as we anticipated the invention of video-phones and pocket computers and household robots, as our conceptual bounds for the human story were pushed ever farther outward.

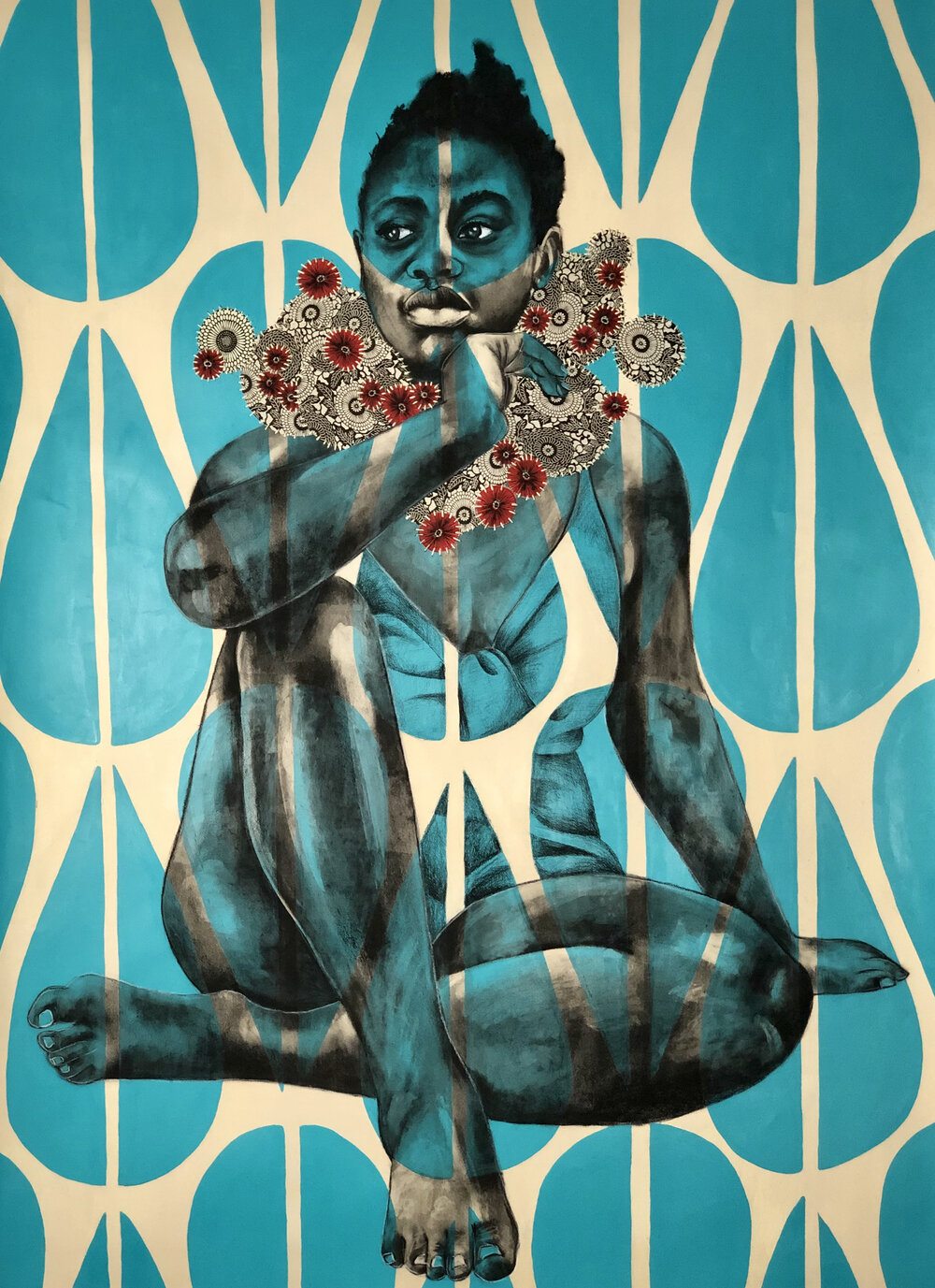

On February 18, 2021, NASA landed Perseverance rover on the surface of Mars. Perseverance is the latest of some twenty probes that NASA has sent to bring back detailed information about our neighboring planet, beginning with the Mariner spacecraft fly-by in 1965, which took the first closeup photograph. Though blurry by today’s standards, those grainy images helped ignite widespread wonder and fantasy about space exploration, not long before Star Trek also debuted on television. By the 1970s, science-fiction storytelling was moving from the margins of pop-culture into the mainstream in film and television—and so followed generations of kids, like myself, who grew up expecting off-world adventurism and alien encounters almost as much as we anticipated the invention of video-phones and pocket computers and household robots, as our conceptual bounds for the human story were pushed ever farther outward. Delita Martin. Rain Falls From The Lemon Tree. 2020

Delita Martin. Rain Falls From The Lemon Tree. 2020 It’s been 40 years this past month since the election of François Mitterrand as President of France. Today, June 21, is the day chosen by his first Minister of Culture for the

It’s been 40 years this past month since the election of François Mitterrand as President of France. Today, June 21, is the day chosen by his first Minister of Culture for the

When we were young, most of us indulged in the speculation, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” Many of us said things like a firefighter, a doctor, a nurse, or a teacher. As children, we instinctively looked at the world around us and recognized the careers that seemed to have purpose and meaning, and that seemed to make the world a better place. I can’t imagine that many 5-years olds dreamed of being paper pushers or spending their days doing data entry. But we grow up. People around us have expectations for us; we have expectations for ourselves. We might have academic challenges, financial needs, family obligations. We see the world and the careers open to us as more diverse and as more challenging than the Fisher-Price Little People figures that characterize the world for a child. And so, many of us lose that childhood idealism and just get a job, get on the career ladder, put our noses to the grindstone.

When we were young, most of us indulged in the speculation, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” Many of us said things like a firefighter, a doctor, a nurse, or a teacher. As children, we instinctively looked at the world around us and recognized the careers that seemed to have purpose and meaning, and that seemed to make the world a better place. I can’t imagine that many 5-years olds dreamed of being paper pushers or spending their days doing data entry. But we grow up. People around us have expectations for us; we have expectations for ourselves. We might have academic challenges, financial needs, family obligations. We see the world and the careers open to us as more diverse and as more challenging than the Fisher-Price Little People figures that characterize the world for a child. And so, many of us lose that childhood idealism and just get a job, get on the career ladder, put our noses to the grindstone. The desire to turn failure into a learning opportunity is often generous, and an important way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life. I first became aware of it as a frequent trope in start-up culture, where, influenced by practices in software development where trying things out and failing is the quickest way to get to something of value, we are constantly subject to exhortations to “fail fast and fail forward”. Many workplaces now lionise (whether sincerely or not is another matter) the importance of learning through failure, and of creating environments that encourage this.

The desire to turn failure into a learning opportunity is often generous, and an important way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life. I first became aware of it as a frequent trope in start-up culture, where, influenced by practices in software development where trying things out and failing is the quickest way to get to something of value, we are constantly subject to exhortations to “fail fast and fail forward”. Many workplaces now lionise (whether sincerely or not is another matter) the importance of learning through failure, and of creating environments that encourage this.

If you’d like to start at the beginning, read

If you’d like to start at the beginning, read

John Betjeman’s life at Oxford was complicated. He wrote poems and made friends, he discovered beauty and rejoiced in it, but he struggled academically, in part because of an impossible relationship with his tutor, who thought him an “idle prig” and did nothing to disguise his hostility. The tutor complained about Betjeman’s silly aestheticism in his diary, but didn’t confine himself to private musings: He treated Betjeman with open contempt, and when Betjeman needed a supportive letter from him, he wrote a rather obviously unsupportive one––which was one reason among several that Betjeman never managed to graduate. What the tutor did not realize was that Betjeman’s frivolous manner was a kind of protective carapace, a way to shield himself from suffering and emotional upheaval.

John Betjeman’s life at Oxford was complicated. He wrote poems and made friends, he discovered beauty and rejoiced in it, but he struggled academically, in part because of an impossible relationship with his tutor, who thought him an “idle prig” and did nothing to disguise his hostility. The tutor complained about Betjeman’s silly aestheticism in his diary, but didn’t confine himself to private musings: He treated Betjeman with open contempt, and when Betjeman needed a supportive letter from him, he wrote a rather obviously unsupportive one––which was one reason among several that Betjeman never managed to graduate. What the tutor did not realize was that Betjeman’s frivolous manner was a kind of protective carapace, a way to shield himself from suffering and emotional upheaval. Alexander Polyakov

Alexander Polyakov

Like many public intellectuals who are worth reading,

Like many public intellectuals who are worth reading,  In Akwaeke Emezi’s new book,

In Akwaeke Emezi’s new book,