Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

MALALA YOUSAFZAI IS FREAKING OUT about the future. The now twenty-three year old says so in an interview given to British Vogue, which has featured her clad in a blood-red outfit with matching headscarf on its July cover. Inside is a luscious photo spread and the kind of cutesy confessions that one would expect from a woman sentenced to being a girl forever: she was not chosen as head girl at school, she confesses; she loved being at Oxford and ordering takeout whenever she pleased. In this interview, as in most others of the thousands she has given, the interviewer emphasizes her ordinariness; Malala likes to take selfies, we learn, and her standing order at McDonalds is a sweet chili chicken wrap and a caramel frappe. In these revelations is the assurance that Malala Yousafzai, the girl wonder who fought the Taliban, is still the innocent and monochromatic figure the world needs her to be.

MALALA YOUSAFZAI IS FREAKING OUT about the future. The now twenty-three year old says so in an interview given to British Vogue, which has featured her clad in a blood-red outfit with matching headscarf on its July cover. Inside is a luscious photo spread and the kind of cutesy confessions that one would expect from a woman sentenced to being a girl forever: she was not chosen as head girl at school, she confesses; she loved being at Oxford and ordering takeout whenever she pleased. In this interview, as in most others of the thousands she has given, the interviewer emphasizes her ordinariness; Malala likes to take selfies, we learn, and her standing order at McDonalds is a sweet chili chicken wrap and a caramel frappe. In these revelations is the assurance that Malala Yousafzai, the girl wonder who fought the Taliban, is still the innocent and monochromatic figure the world needs her to be.

An exception to this assessment, which may be worse, can be found in Pakistan. Over there, the need to counter the country’s reputation as the site of Malala’s cruel militant mauling in 2012 has produced a vicious desire to police her life and movements abroad. When a photo of Malala wearing skinny jeans made the rounds on social media a few years ago, the Pakistani right was only too willing to list in great detail all the ways in which she had failed her faith/country/tribe and so on. If the West wishes to see Malala as the perpetual brave girl, the Pakistani religious right wants to present her as a crafty woman, and an errant one at that. It makes sense, then, that Malala has not chosen, at least at the moment, to live in Pakistan, where her scars remind everyone of their shameful inability to protect a young girl who spoke out for girls’ rights to education.

Pakistan is in Malala’s past. The celebrity world of international renown, red carpets, and millions and millions of dollars for her Malala Fund NGO are her current reality. It’s the flip side of Pakistan, a realm that is particularly attuned to the framework of her story as a young Muslim girl shot in the head by rabid and bloodthirsty Muslim men. As the scholar Shenila Khoja-Moolji has noted, the enduring and all-encompassing strength of this narrative is such that the individual, even Malala herself, is erased from it.

More here.

We can sometimes forget that “India”—or the idea of a single unified entity—is not a very old concept. Indian history is complicated and convoluted: different societies, polities and cultures rise and fall, ebb and flow, as the political makeup of South Asia changes.

We can sometimes forget that “India”—or the idea of a single unified entity—is not a very old concept. Indian history is complicated and convoluted: different societies, polities and cultures rise and fall, ebb and flow, as the political makeup of South Asia changes.

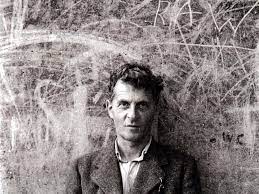

What exactly did Wittgenstein learn from his students? More than a few answers lie in Wörterbuch für Volksschulen (Word book for elementary schools), a curious artifact from his schoolmaster years. Wittgenstein was dissatisfied with existing spelling books, which were expensive and bulky and therefore scarce. One of the tasks in his classroom was for his students to create their own vocabulary list copied from what he wrote on the chalkboard. But production was time-consuming, and the quality was hard to control. If every student had their own slim wordbook, though, they could correct their own errors. These issues with the standard ways of making vocabulary lists led Wittgenstein to write the Wörterbuch, which was published in 1926, the year he quit teaching. For a few years it was used in Austrian village schools, and then it went out of print.

What exactly did Wittgenstein learn from his students? More than a few answers lie in Wörterbuch für Volksschulen (Word book for elementary schools), a curious artifact from his schoolmaster years. Wittgenstein was dissatisfied with existing spelling books, which were expensive and bulky and therefore scarce. One of the tasks in his classroom was for his students to create their own vocabulary list copied from what he wrote on the chalkboard. But production was time-consuming, and the quality was hard to control. If every student had their own slim wordbook, though, they could correct their own errors. These issues with the standard ways of making vocabulary lists led Wittgenstein to write the Wörterbuch, which was published in 1926, the year he quit teaching. For a few years it was used in Austrian village schools, and then it went out of print. ‘Art, considered as the expression of any people as a whole, is the response they make in various mediums to the impact that the totality of their experience makes upon them, and there is no sort of experience that works so constantly and subtly upon man as his regional environment,’ wrote Mary Austin in The English Journal in 1932. ‘It orders and determines all the direct, practical ways of his getting up and lying down, of staying in and going out, of housing and clothing and food-getting; it arranges by its progressions of seed times and harvest, its rain and wind and burning suns, the rhythms of his work and amusements. It is the thing always before his eye, always at his ear, always underfoot.’

‘Art, considered as the expression of any people as a whole, is the response they make in various mediums to the impact that the totality of their experience makes upon them, and there is no sort of experience that works so constantly and subtly upon man as his regional environment,’ wrote Mary Austin in The English Journal in 1932. ‘It orders and determines all the direct, practical ways of his getting up and lying down, of staying in and going out, of housing and clothing and food-getting; it arranges by its progressions of seed times and harvest, its rain and wind and burning suns, the rhythms of his work and amusements. It is the thing always before his eye, always at his ear, always underfoot.’ MALALA YOUSAFZAI IS FREAKING OUT

MALALA YOUSAFZAI IS FREAKING OUT Few harbingers of old age are clearer than the sight of gray hair. As we grow older, black, brown, blonde or red strands lose their youthful hue. Although this may seem like a permanent change, new research reveals that the graying process can be undone—at least temporarily. Hints that gray hairs could spontaneously regain color have existed as isolated case studies within the scientific literature for decades. In one 1972 paper, the late dermatologist Stanley Comaish reported an encounter with a 38-year-old man who had what he described as a “

Few harbingers of old age are clearer than the sight of gray hair. As we grow older, black, brown, blonde or red strands lose their youthful hue. Although this may seem like a permanent change, new research reveals that the graying process can be undone—at least temporarily. Hints that gray hairs could spontaneously regain color have existed as isolated case studies within the scientific literature for decades. In one 1972 paper, the late dermatologist Stanley Comaish reported an encounter with a 38-year-old man who had what he described as a “ My impression is that the police in New York have tempered their initially confrontational approach to the protesters. There were no barricades or cars set up to entrap and enclose marchers. It seemed to me that, slowly, some lessons are being learned. But not everywhere — in Atlanta,

My impression is that the police in New York have tempered their initially confrontational approach to the protesters. There were no barricades or cars set up to entrap and enclose marchers. It seemed to me that, slowly, some lessons are being learned. But not everywhere — in Atlanta,  As dinosaurs lumbered through the

As dinosaurs lumbered through the  The signature of our current debate about free speech is that it is not primarily about protecting speech from the government. Rather, it is about the “culture of free speech.” It’s about intellectual openness and diversity as a cultural norm to be embraced by private individuals and private institutions.

The signature of our current debate about free speech is that it is not primarily about protecting speech from the government. Rather, it is about the “culture of free speech.” It’s about intellectual openness and diversity as a cultural norm to be embraced by private individuals and private institutions. Fiction:

Fiction: In February, China

In February, China  To understand the strength of Putin’s position when it comes to defending Russian international interests (as opposed to domestic interests, where his deeply corrupt set-up is becoming increasingly unpopular), it is vital to understand that while Putin is obviously much more personally powerful than Western leaders, he is still the leader of the Russian foreign and security establishment — or as former Obama adviser Ben Rhodes dubbed the US equivalent, a blob.

To understand the strength of Putin’s position when it comes to defending Russian international interests (as opposed to domestic interests, where his deeply corrupt set-up is becoming increasingly unpopular), it is vital to understand that while Putin is obviously much more personally powerful than Western leaders, he is still the leader of the Russian foreign and security establishment — or as former Obama adviser Ben Rhodes dubbed the US equivalent, a blob.

Some years ago a friend brought us to see the town of Acitrezza in Sicily where, arguably, the first great neorealist film was made. La Terra Trema (The Earth Trembles) was, according to its director, Luchino Visconti, filmed with actors “chosen from among the inhabitants of this town: fishermen, girls, labourers, stonemasons, fish wholesalers”. The dialogue was Sicilian, very much a language in itself and coeval with Italian. Our friend told us that the woman who played one of the sisters, Lucia, who is seduced by the marshal Don Salvatore in the film, was afterwards rejected by her community and never found a husband because they believed she had become a whore. The story may be a kind of urban legend, but there are so many layers to it that it’s worth unpacking a little.

Some years ago a friend brought us to see the town of Acitrezza in Sicily where, arguably, the first great neorealist film was made. La Terra Trema (The Earth Trembles) was, according to its director, Luchino Visconti, filmed with actors “chosen from among the inhabitants of this town: fishermen, girls, labourers, stonemasons, fish wholesalers”. The dialogue was Sicilian, very much a language in itself and coeval with Italian. Our friend told us that the woman who played one of the sisters, Lucia, who is seduced by the marshal Don Salvatore in the film, was afterwards rejected by her community and never found a husband because they believed she had become a whore. The story may be a kind of urban legend, but there are so many layers to it that it’s worth unpacking a little. The Emancipation Proclamation, some forget, was not the sweeping, all-encompassing document that it is often remembered as. It applied only to the eleven Confederate states and did not include the border states that had remained loyal to the U.S., where it was still legal to own enslaved people. Despite the order of the proclamation, Texas was one of the Confederate states that ignored what it demanded. And even though many enslaved people escaped behind Union lines and enlisted in the Federal Army themselves, enslavers throughout the Confederacy continued to hold Black people in bondage throughout the rest of the war. General Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, in Appomattox County, Virginia, effectively signaling that the Confederacy had lost the war, but many enslavers in Texas did not share this news with their human property. It was on June 19, 1865, soon after arriving in Galveston, that Granger issued the announcement, known as General Order Number 3, that all slaves were free and word began to spread throughout Texas, from plantation to plantation, farmstead to farmstead, person to person.

The Emancipation Proclamation, some forget, was not the sweeping, all-encompassing document that it is often remembered as. It applied only to the eleven Confederate states and did not include the border states that had remained loyal to the U.S., where it was still legal to own enslaved people. Despite the order of the proclamation, Texas was one of the Confederate states that ignored what it demanded. And even though many enslaved people escaped behind Union lines and enlisted in the Federal Army themselves, enslavers throughout the Confederacy continued to hold Black people in bondage throughout the rest of the war. General Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, in Appomattox County, Virginia, effectively signaling that the Confederacy had lost the war, but many enslavers in Texas did not share this news with their human property. It was on June 19, 1865, soon after arriving in Galveston, that Granger issued the announcement, known as General Order Number 3, that all slaves were free and word began to spread throughout Texas, from plantation to plantation, farmstead to farmstead, person to person.