Michael Fried at nonsite:

Specifically, I want to suggest that the advent of Impressionism around 1870 marks a fundamental break in what I will call the dialectical continuity of French painting going back to the middle of the eighteenth century, when a new conception of the absorptive and dramatic tableau came to the fore in the paintings of Jean-Baptiste Greuze (themselves inconceivable apart from the precedent of the genre paintings of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin) and the art critical and theoretical writings of the polymath philosophe Denis Diderot, the founder of art criticism as we know it. This is the fateful development analyzed in my 1980 book, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot, in which I argue (I would like to think I demonstrate) that starting in the mid-1750s and 1760s in France the art of painting found it necessary to confront a new imperative: to find the means to suspend or neutralize—to somehow wall off—the now suddenly distracting presence of the beholder; or to put this slightly differently, to somehow establish the supreme fiction or ontological illusion that the beholder does not exist, that there is no one standing before the painting. I describe this imperative in terms of a need to stave off, if possible to overcome, a newly distinct danger of theatricality. And I argue that this was to be accomplished with the aide of two principal strategies: first, the thematization of absorption, which is to say the depiction of personages each of whom was felt to be entirely caught up (absorbed) in whatever was understood to be taking place within the representation; and second, the promotion of a new, more exigent ideal of dramatic unity, according to which all the elements in the painting were directed toward a single dramatic end, thereby achieving a compositional effect of closure vis-à-vis the beholder.

Specifically, I want to suggest that the advent of Impressionism around 1870 marks a fundamental break in what I will call the dialectical continuity of French painting going back to the middle of the eighteenth century, when a new conception of the absorptive and dramatic tableau came to the fore in the paintings of Jean-Baptiste Greuze (themselves inconceivable apart from the precedent of the genre paintings of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin) and the art critical and theoretical writings of the polymath philosophe Denis Diderot, the founder of art criticism as we know it. This is the fateful development analyzed in my 1980 book, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot, in which I argue (I would like to think I demonstrate) that starting in the mid-1750s and 1760s in France the art of painting found it necessary to confront a new imperative: to find the means to suspend or neutralize—to somehow wall off—the now suddenly distracting presence of the beholder; or to put this slightly differently, to somehow establish the supreme fiction or ontological illusion that the beholder does not exist, that there is no one standing before the painting. I describe this imperative in terms of a need to stave off, if possible to overcome, a newly distinct danger of theatricality. And I argue that this was to be accomplished with the aide of two principal strategies: first, the thematization of absorption, which is to say the depiction of personages each of whom was felt to be entirely caught up (absorbed) in whatever was understood to be taking place within the representation; and second, the promotion of a new, more exigent ideal of dramatic unity, according to which all the elements in the painting were directed toward a single dramatic end, thereby achieving a compositional effect of closure vis-à-vis the beholder.

more here.

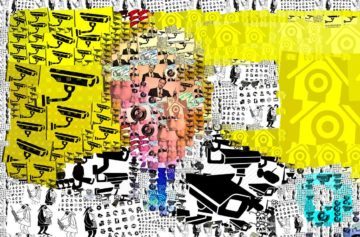

The Trump years have transformed the Greater Evil Party, formerly known as the GOP, into a party too appalling even to contemplate without going berserk. Alarmists expected all sorts of bad things to come from the Trump presidency, but no one quite expected this. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party has sprouted a left wing too extensive and organized for that wretched party’s leaders and donors to marginalize. Even after the Occupy movements of 2011 and the Sanders campaign in 2016, this too was unexpected. It is also, by far, the best thing that has happened in American politics in decades. It probably would not have happened but for Trump. Who would have expected that? Who could have imagined that his unmitigated vileness and his incompetence would have had that unintended effect? It did, though. And so, calls for social policies comparable to those achieved in advanced social democracies a half century ago have become almost mainstream. More amazing still, thanks to Trump more than anyone else, the word “socialism” need no longer be uttered only in whispers in Democratic Party circles.

The Trump years have transformed the Greater Evil Party, formerly known as the GOP, into a party too appalling even to contemplate without going berserk. Alarmists expected all sorts of bad things to come from the Trump presidency, but no one quite expected this. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party has sprouted a left wing too extensive and organized for that wretched party’s leaders and donors to marginalize. Even after the Occupy movements of 2011 and the Sanders campaign in 2016, this too was unexpected. It is also, by far, the best thing that has happened in American politics in decades. It probably would not have happened but for Trump. Who would have expected that? Who could have imagined that his unmitigated vileness and his incompetence would have had that unintended effect? It did, though. And so, calls for social policies comparable to those achieved in advanced social democracies a half century ago have become almost mainstream. More amazing still, thanks to Trump more than anyone else, the word “socialism” need no longer be uttered only in whispers in Democratic Party circles. Mind-wandering is often considered a harmless quirk, as in the cliché of the scatter-brained professor. But it has real consequences. Let’s begin with the bad ones. Absentminded people perform less well on tests that require focused attention, such as reading comprehension tests. More worrisome, they also perform more poorly on tests that you better not flunk if you have any career aspirations. Among them is the Scholastic Aptitude Test that many colleges require for admission. But mind-wandering also has an upside—at least for well-trained minds. Indeed, many anecdotes of creators like Einstein, Newton, and eminent mathematician Henri Poincaré, report that these scientists solved important problems while not actually working on anything. The common wisdom that the best ideas arrive in the shower is exemplified by Archimedes’s discovery of how to measure an object’s volume. (OK, he was in a bathtub.) But while Archimedes’s discovery was triggered by the rising water as he entered the tub, other breakthroughs surface apropos of nothing. Take this well-known quote from the Poincaré describing a period in his life when he had worked without success on a mathematical problem:

Mind-wandering is often considered a harmless quirk, as in the cliché of the scatter-brained professor. But it has real consequences. Let’s begin with the bad ones. Absentminded people perform less well on tests that require focused attention, such as reading comprehension tests. More worrisome, they also perform more poorly on tests that you better not flunk if you have any career aspirations. Among them is the Scholastic Aptitude Test that many colleges require for admission. But mind-wandering also has an upside—at least for well-trained minds. Indeed, many anecdotes of creators like Einstein, Newton, and eminent mathematician Henri Poincaré, report that these scientists solved important problems while not actually working on anything. The common wisdom that the best ideas arrive in the shower is exemplified by Archimedes’s discovery of how to measure an object’s volume. (OK, he was in a bathtub.) But while Archimedes’s discovery was triggered by the rising water as he entered the tub, other breakthroughs surface apropos of nothing. Take this well-known quote from the Poincaré describing a period in his life when he had worked without success on a mathematical problem: On Christmas Day 1989 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Leonard Bernstein

On Christmas Day 1989 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Leonard Bernstein

For those, like me, living far from home, there is a worry so common it is banal: the Call. The call that comes when a loved one is hurt or dying. We brace ourselves against it, convinced that anticipation is inoculation against grief. To this day, I sleep with my phone on silent only when I am back in Pakistan; home is the place where late-night calls don’t seize the ground beneath you.

For those, like me, living far from home, there is a worry so common it is banal: the Call. The call that comes when a loved one is hurt or dying. We brace ourselves against it, convinced that anticipation is inoculation against grief. To this day, I sleep with my phone on silent only when I am back in Pakistan; home is the place where late-night calls don’t seize the ground beneath you. When asked to describe the circumstances of her birth, the

When asked to describe the circumstances of her birth, the  The summer solstice scene is loose and dewy, flower-crowned crowds in debauch around the bonfires. People leaped over flames and the tongues of flame licked up high into the night. In winter: private fires. Home hearths. These fires “have such power over our memory that the ancient lives slumbering beyond our oldest recollections awaken with us …revealing the deepest regions of our secret souls,” writes Henri Bosco in Malicroix. The Yule log didn’t start as a cocoa confection with meringue mushrooms on the top. It was oak burned on the night of the solstice. Depending where one lived, the ashes of the solstice fire were then spread on fields over the following days to up the yield of next season’s crop, or fed to cattle to up fatness and fertility of the herd, or placed under beds to protect against thunder, or sometimes worn in a vial around the neck. The ancient cults cast shadows in our minds, shift and flicker, their fears are still our fears, down in the darkest places of ourselves.

The summer solstice scene is loose and dewy, flower-crowned crowds in debauch around the bonfires. People leaped over flames and the tongues of flame licked up high into the night. In winter: private fires. Home hearths. These fires “have such power over our memory that the ancient lives slumbering beyond our oldest recollections awaken with us …revealing the deepest regions of our secret souls,” writes Henri Bosco in Malicroix. The Yule log didn’t start as a cocoa confection with meringue mushrooms on the top. It was oak burned on the night of the solstice. Depending where one lived, the ashes of the solstice fire were then spread on fields over the following days to up the yield of next season’s crop, or fed to cattle to up fatness and fertility of the herd, or placed under beds to protect against thunder, or sometimes worn in a vial around the neck. The ancient cults cast shadows in our minds, shift and flicker, their fears are still our fears, down in the darkest places of ourselves. Amy Nitza has spent decades helping people in crisis. The director of the Institute for Disaster Mental Health at the State University of New York at New Paltz has traveled to Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Maria, to Botswana during an HIV crisis and to Haiti to help traumatized children forced into domestic servitude. But the COVID-19 pandemic, Nitza says, is different. It keeps coming at people month after month as loved ones get sick or die, as jobs are lost, and as the actions taken to avoid infection—such as isolation from family—cause intense emotional pain and stress. As of December 2020, more than 1.6 million people around the globe have died from the coronavirus. Grief, fear and economic hardship have hit every nation. In the U.S. the numbers have been overwhelming: more than 300,000 people have died, and about 17 million have been infected with the virus, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Usually disasters have survivors and responders, Nitza says, but COVID is so widespread that people are both of those things at once. “We’re training everybody [on] how to take care of themselves and how to support the people around them,” she says.

Amy Nitza has spent decades helping people in crisis. The director of the Institute for Disaster Mental Health at the State University of New York at New Paltz has traveled to Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Maria, to Botswana during an HIV crisis and to Haiti to help traumatized children forced into domestic servitude. But the COVID-19 pandemic, Nitza says, is different. It keeps coming at people month after month as loved ones get sick or die, as jobs are lost, and as the actions taken to avoid infection—such as isolation from family—cause intense emotional pain and stress. As of December 2020, more than 1.6 million people around the globe have died from the coronavirus. Grief, fear and economic hardship have hit every nation. In the U.S. the numbers have been overwhelming: more than 300,000 people have died, and about 17 million have been infected with the virus, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Usually disasters have survivors and responders, Nitza says, but COVID is so widespread that people are both of those things at once. “We’re training everybody [on] how to take care of themselves and how to support the people around them,” she says. I

I  One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

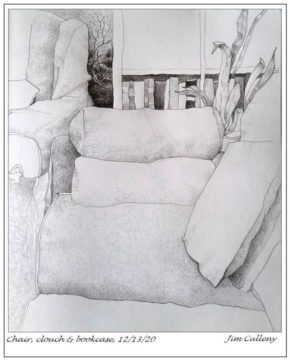

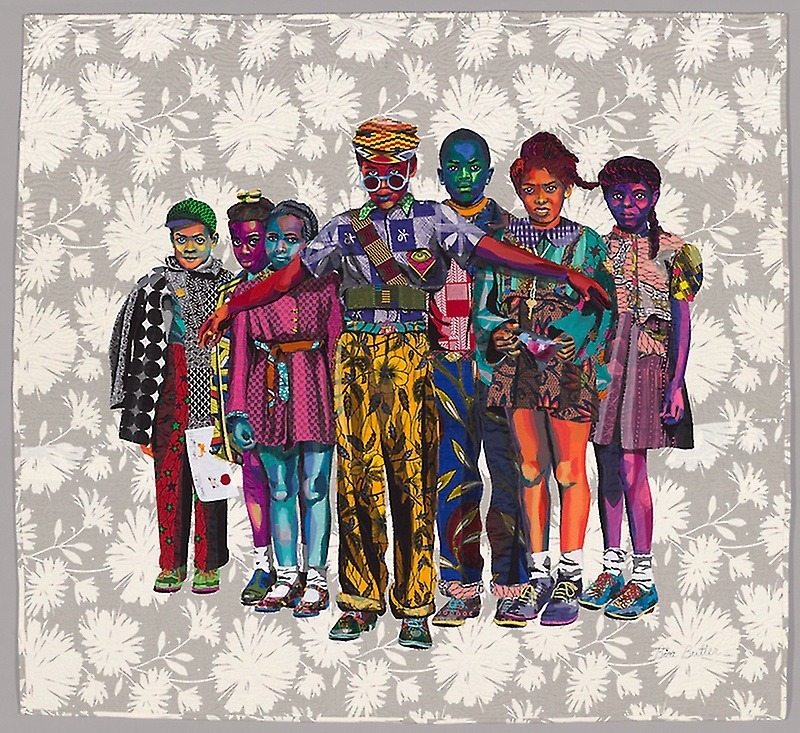

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.