Month: December 2020

Life Inside a Pre-Release Center: Like Prison, But More Work

Lindsay Beyerstein in Vice:

Lindsay Beyerstein in Vice:

There’s a converted three-story hotel on the industrial south side of Billings, Montana. It’s next to a large funeral home and down the street from the Montana Women’s Prison. From the outside, it looks like a nursing home, painted pink and beige, with a semi-circular driveway, and blue sign bearing the vague name “Passages.” The vibe is therapeutic but definitely not optional. It’s a place without barbed wire or armed guards, but not a place you can just leave.

The building is home to Passages, one of eight privately-owned pre-release facilities in Montana and one of only two exclusively for women. Like all pre-release centers, Passages is owned by a non-profit corporation that operates under contract to the Montana Department of Corrections (DOC). Pre-release centers are a fixture of Montana’s correctional system, and they are also used in other states including Massachusetts, Maryland, and South Carolina, as well as throughout the federal prison system.

When I approach the reception desk, I am asked to surrender my ID, “in case there’s a fire in the building.” The bright hall carpet and the breakfast bar on the ground floor are reminders of the building’s past as a Howard Johnson’s. A sign warns that escape is punishable by up to 10 years in prison.

More here.

On Integration

Jesse McCarthy and Jon Baskin in The Point:

Jesse McCarthy and Jon Baskin in The Point:

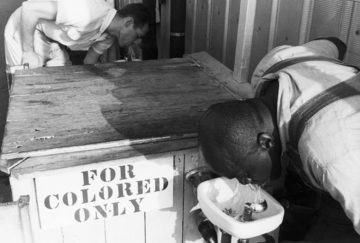

This summer, amid the ongoing protests for racial justice, Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility once again shot up the best-seller lists. The book, which had already been a huge success on the diversity-training circuit and had received mixed, but muted, responses from intellectual commentators, was now subjected to a symptomatic backlash. This began with left intellectuals taking DiAngelo to task for her focus on workplace harmony at the expense of attention to capitalism or structural inequalities like housing discrimination. It continued with liberals and conservatives chiding the book for its racial essentialism and its discounting of individual agency. And it culminated with the White House statement banning trainings that reflect DiAngelo’s methodology in the federal government: terms like “white privilege” and “systemic racism,” the Trump administration alleged, are both divisive and “un-American.”

If nothing else, the sales figures for White Fragility and its partners in the ascendant genre of antiracist pedagogy—as of this writing, White Fragility is joined on the best-seller list by Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist and Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race—testifies to how ludicrous it is to call such books “un-American.” In fact, their blend of puritanical hectoring, etiquette training, “lucid definitions” and self-help is as American as apple pie. That is both their appeal and their fatal limitation. “Nothing in mainstream US culture,” DiAngelo writes, “gives us the information we need to have the nuanced understanding of arguably the most complex and enduring social dynamic of the last several hundred years.” Fair enough. But a reader is then entitled to believe this lacuna will now be filled, preferably with the information and historical context that can lead to that nuanced understanding. Instead, what is on offer is patently not content but form, not information but reformation, not education but therapy—not a correction of the superficiality of mainstream American commentary and culture but a complement to it. This accounts for why what gets produced by books like White Fragility seems so depressingly familiar.

More here.

The Scars of Democracy

Peter Gordon in The Nation:

Peter Gordon in The Nation:

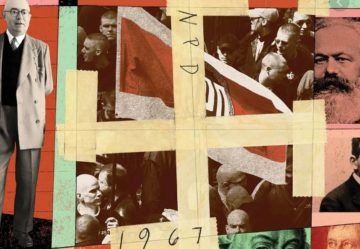

n April 6, 1967, Theodor W. Adorno accepted an invitation from the Association of Socialist Students at the University of Vienna to deliver a lecture on “aspects of the new right-wing extremism.” The topic held a special urgency: The National Democratic Party, a recently founded neofascist group in West Germany, was surging in popularity and would soon surpass the official 5 percent threshold needed to secure representation in seven of Germany’s 11 regional parliaments. In Europe after World War II, Adorno was highly esteemed not only for his philosophical and cultural writings but also for his analysis of the fascist tendencies that still survived in the so-called liberal democratic orders of the capitalist West, and the students and socialist activists gathered in Vienna were eager to hear his thoughts.

The lecture, though brief, addressed the specific instances of a neofascist resurgence in postwar West Germany. And it spoke to the general question of what fascism is and how we should think about challenges to liberal democracy that come from the extreme right. Liberal democracies, Adorno argued, are by their nature fragile; they are riven with contradictions and vulnerable to systemic abuse, and their stated ideals are so frequently violated in practice that they awaken resentment, opposition, and a yearning for extrasystemic solutions. Those who defend democracy must confront the persistent inequalities that breed this resentment and that prevent democracy from becoming what it claims to be.

Newly transcribed from a tape recording and now published in an English translation under the title Aspects of the New Right-Wing Extremism, the lecture reminds us of Adorno’s political engagement into the late 1960s.

More here.

Caste Does Not Explain Race

Charisse Burden-Stelly in Boston Review:

Charisse Burden-Stelly in Boston Review:

In the late 1940s, the Cold War was heating up. In the United States, anticommunism had reached a fever pitch at the same time that antiblack violence had forcefully re-emerged in the form of lynching and race riots. At this auspicious moment, Lincoln University historical sociologist Oliver Cromwell Cox published his 624-page tour de force, Caste, Class, and Race: A Study in Social Dynamics (1948). Cox’s book put class struggle, racial violence, and relentless political-class competition at the founding of the capitalist world-system in 1492, though it argued that these constitutive features had existed in nascent form since much earlier. Cox contended that economic exploitation was at the root of U.S. racial hierarchy. In particular, it was responsible for structuring relations among the white ruling class, the white masses, and Black people as a racialized class of workers.

Cox’s book refuted the “caste school” of race relations. For nearly a decade, Cox had challenged scholars who compared U.S. race relations to the caste system in India—caste being a religious-social structure that preceded the rise of capitalism. In a 1942 article, “The Modern Caste School of Race Relations,” Cox noted that, despite their claims to originality, researchers such as W. Lloyd Warner, Allison Davis, and John Dollard were simply recapitulating a caste hypothesis that had been “quite popular” in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Cox did not speculate why—in the context of the Great Depression, ascending fascism, and increased racial violence—the caste hypothesis had been “made fashionable” again. However, he noted that the resurgence of caste as a model for explaining the racial order in the United States separated race relations from class politics just when a racialized struggle over resources was intensifying.

More here.

NATO, Past and Future

The New Left Review has introduced a blog, Sidecar. Wolfgang Streeck in Sidecar:

The New Left Review has introduced a blog, Sidecar. Wolfgang Streeck in Sidecar:

President Biden is not yet in office, but the sighs of relief in Europe’s polite political society are ear-splitting – anyone but Trump! In Germany, where people always have a firm view on whom other people must and must not elect, 95 percent rejoice that Trump is gone. Note, however, that while he may be gone as POTUS, there is a good chance, unless he goes to jail, but perhaps even then, that he will continue to be a powerful presence as leader of a powerful United States’ disloyal opposition.

In any case, hoping for the good old days of hyperglobalization to return, and ‘populism’ to vanish into the dark, European politicians are revelling in happy narratives of rule-bound multilateral global governance in the good old liberal international order (LIO), when an incoming American president could be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize as a thank you just for taking office – conjuring up a past that never was, in a desperate effort to turn it into a future that never will be. In the lead are the Germans, in Berlin and Brussels (where Frau von der Leyen is working overtime to express transatlantic enthusiasm). Included in their love letters to Washington is a mysterious morning gift: a promise that ‘the Europeans’ will from now on carry a ‘larger share’ of the ‘common burden’ and accept more ‘responsibility’ for themselves and the ‘West’.

What burden? What responsibility? What have ‘we’ failed to do in the past that ‘we’ will do in the future, now that the bad President is succeeded by a good President?

More here.

A life in politics: New Left Review at 50

Stefan Collini in The Guardian:

Stefan Collini in The Guardian:

New Left Review at 50: no balloons, of course, and definitely no party games. The very idea of “celebration” smacks of consumerist pseudo-optimism. Mere chronology is, after all, an untheorised concept. We should see it as not so much an anniversary, more an over-determined conjuncture.

It is hard not to be intimidated by New Left Review. At times, the journal can seem like an elaborate contrivance for making us feel inadequate. One’s relation to it conjugates as an irregular verb: I wish I knew more about industrialisation in China; you ought to have a better grasp of Brenner’s analysis of global turbulence; he, she, or it needs to understand the significance of community-based activism in Latin America. For many Guardian readers (and others), the journal functions like a kind of older brother whom we look up to – more serious, better informed, better travelled, stronger, irreplaceable. Well, maybe a tiny bit solemn at times (we could draw lots for who gets the job of telling Perry Anderson to lighten up), and perhaps when we were out of touch for longish stretches, life seemed a bit easier. But then we meet up and it’s a case of respect at first sight, all over again.

More here.

Edna O’Brien on turning 90: ‘I can’t pretend that I haven’t made mistakes’

Sarah Hughes in The Guardian:

Most people approaching their 90th birthday would be forgiven for deciding that, whatever their work, enough was enough and it was time to relax. Most people, however, are not Edna O’Brien. Ireland’s greatest living writer has over the past week delivered this year’s TS Eliot lecture on Eliot and James Joyce for Dublin’s Abbey Theatre – Covid-19 meant that it was recorded at the Irish Embassy in London and will be broadcast on her birthday – and won the South Bank Sky Arts award for literature for her recent novel, Girl, a harrowing, heartbreaking tale about the girls kidnapped in Nigeria by Boko Haram. On Tuesday she celebrates her birthday.

Most people approaching their 90th birthday would be forgiven for deciding that, whatever their work, enough was enough and it was time to relax. Most people, however, are not Edna O’Brien. Ireland’s greatest living writer has over the past week delivered this year’s TS Eliot lecture on Eliot and James Joyce for Dublin’s Abbey Theatre – Covid-19 meant that it was recorded at the Irish Embassy in London and will be broadcast on her birthday – and won the South Bank Sky Arts award for literature for her recent novel, Girl, a harrowing, heartbreaking tale about the girls kidnapped in Nigeria by Boko Haram. On Tuesday she celebrates her birthday.

It will, she says, be a relatively quiet affair. “I’m going to see my agent and my son Sasha, and there will be one other person – I hope that’s allowed. My other son, Carlo, lives in Enniskillen [in Northern Ireland] so he can’t come.”

There is something magical about being in O’Brien’s company. It’s not simply that at almost 90 she remains a bewitching presence, tiny, beautifully dressed in black jacket and skirt with an intricate silver necklace, her red hair perfectly styled. Her house itself, a narrow terrace in London’s Chelsea which she rents, has an aura about it from the cosy downstairs kitchen to the book-stacked shelves of her office – “The books are taking over,” she laughs at one point. “They’re everywhere…”

More here.

Donald Trump’s Final Act: Snuffing Out the Promise of Democracy in the Middle East

Vijay Prashad in Counterpunch:

Ten years ago, a hawker in Tunisia set himself on fire, which spurred on people along the entire Mediterranean Sea—from Morocco to Spain—to rise up in revolt. They took to their squares indignant at the terrible conditions in which they had to make their lives. Little of their agenda has been advanced in the past decade. Governments of the southern European states have one by one betrayed the aspirations of the people; the most dramatic such failure was of the Syriza government in Greece, which won a mandate against austerity and then surrendered before the troika (the European Central Bank, the European Commission, and the International Monetary Fund) in 2015.

Ten years ago, a hawker in Tunisia set himself on fire, which spurred on people along the entire Mediterranean Sea—from Morocco to Spain—to rise up in revolt. They took to their squares indignant at the terrible conditions in which they had to make their lives. Little of their agenda has been advanced in the past decade. Governments of the southern European states have one by one betrayed the aspirations of the people; the most dramatic such failure was of the Syriza government in Greece, which won a mandate against austerity and then surrendered before the troika (the European Central Bank, the European Commission, and the International Monetary Fund) in 2015.

Uprisings in northern Africa ended with the return of the generals (as in Egypt), the destruction of states (as in Libya), and the assertion of the Arab monarchies (from Morocco to Saudi Arabia). A decade later, U.S. President Donald Trump carved the obituary on the tombstone of that “Arab Spring” rebellion when he used the immensity of U.S. power to strengthen U.S. allies—such as the Arab monarchies and Israel—to the detriment of the people of the region.

What remains of the Arab Spring is a distant memory of the crowds in Cairo’s Tahrir Square; a better image of the present is that of the monarchs of Morocco and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) kissing up to Israel to please the United States.

More here.

Saturday Poem

I was never one

of those matter-

of-fact mothers

who tell their children

this is thus or what

to do. Though I knew

how to hold my babies

as soon as they were

handed to me, I could feel

how tremendous a life was.

This animal, cradled on my heart, mine

for the naming, how was I to guess

at what it wanted?

Milk, yes. Love, yes. To lie on

me and sleep—yes, yes. But

what I wanted to know

about my babies stitched back

to what I’d been

when I was young—

to what I wanted—

and I couldn’t remember that.

Sometimes, under my baby—

me a boulder, she a lion—

I’d feel our hearts beat

not as one, but stranger

still, as two hearts

pulsing through what

came between them—two

sets of ribs, two muscle walls, two

layers of skin. That I had pushed

my daughters from the dark

unknown of my own

body—I never

got over that.

by Trish Crapo

from Walk Through Paradise Backward

Slate Roof Publishing Collective, 2004

H.M. Naqvi: My Covid Year in Reading

H.M. Naqvi in Literary Hub:

I was in Australia on the tail-end of my eastern book tour, the Last Book Tour perhaps, one that had taken me to Indonesia and Bangladesh earlier, when the plague, after circling for months, dove in for the kill. I left perhaps a week before Australia locked down and have wondered what would have happened if I got stuck Down Under, a world unfamiliar in ways I did not expect. During the tour, however, I spent time on the periphery of stages and outside hotel lobbies, smoking, chatting with local literary rock stars, the likes of Tara June Winch and Christos Tskiolkas. On the plane back home to Karachi, I began Christos’s The Slap, and what a fun ride it was. Christos takes the reader into the minds of very human, rounded, middle-class characters whose lives are upended by an occurrence at a family barbecue in suburban Melbourne. The Slap also helps make an unfamiliar world more familiar.

I was in Australia on the tail-end of my eastern book tour, the Last Book Tour perhaps, one that had taken me to Indonesia and Bangladesh earlier, when the plague, after circling for months, dove in for the kill. I left perhaps a week before Australia locked down and have wondered what would have happened if I got stuck Down Under, a world unfamiliar in ways I did not expect. During the tour, however, I spent time on the periphery of stages and outside hotel lobbies, smoking, chatting with local literary rock stars, the likes of Tara June Winch and Christos Tskiolkas. On the plane back home to Karachi, I began Christos’s The Slap, and what a fun ride it was. Christos takes the reader into the minds of very human, rounded, middle-class characters whose lives are upended by an occurrence at a family barbecue in suburban Melbourne. The Slap also helps make an unfamiliar world more familiar.

Although Covid, for reasons that remain epidemiologically opaque, did not strike Pakistan with the same violence with which it ravaged the region—China, Iran, and now India—I burrowed underground, deep underground upon my return. I don’t want to die before I’m done with my next novel.

More here.

Why mRNA vaccines could revolutionise medicine

Matt Ridley in The Spectator:

Almost 60 years ago, in February 1961, two teams of scientists stumbled on a discovery at the same time. Sydney Brenner in Cambridge and Jim Watson at Harvard independently spotted that genes send short-lived RNA copies of themselves to little machines called ribosomes where they are translated into proteins. ‘Sydney got most of the credit, but I don’t mind,’ Watson sighed last week when I asked him about it. They had solved a puzzle that had held up genetics for almost a decade. The short-lived copies came to be called messenger RNAs — mRNAs – and suddenly they now promise a spectacular revolution in medicine.

Almost 60 years ago, in February 1961, two teams of scientists stumbled on a discovery at the same time. Sydney Brenner in Cambridge and Jim Watson at Harvard independently spotted that genes send short-lived RNA copies of themselves to little machines called ribosomes where they are translated into proteins. ‘Sydney got most of the credit, but I don’t mind,’ Watson sighed last week when I asked him about it. They had solved a puzzle that had held up genetics for almost a decade. The short-lived copies came to be called messenger RNAs — mRNAs – and suddenly they now promise a spectacular revolution in medicine.

The first Covid-19 vaccine given to British people this month is not just a welcome breakthrough against a grim little enemy that has defied every other weapon we have tried, from handwashing to remdesivir and lockdowns. It is also the harbinger of a new approach to medicine altogether. Synthetic messengers that reprogram our cells to mount an immune response to almost any invader, including perhaps cancer, can now be rapidly and cheaply made.

More here.

A mind-boggling optical illusion

Why Did Obama Forget Who Brought Him to the Dance?

Micah L. Sifry in The American Prospect:

I’ve recently spent a good chunk of time engrossed in reading A Promised Land, the first volume of President Barack Obama’s memoirs. After four years of the most impulsive and unstable president of my lifetime, hearing Obama’s calm and judicious voice in my head was like having a long, comforting talk with an old friend. His retelling of the challenges of his first two and a half years, from the global financial crisis and the passage of Obamacare to the Democrats’ midterm collapse in 2010 and the successful operation to kill Osama bin Laden in May 2011, is full of revealing details and discerning insight.

I’ve recently spent a good chunk of time engrossed in reading A Promised Land, the first volume of President Barack Obama’s memoirs. After four years of the most impulsive and unstable president of my lifetime, hearing Obama’s calm and judicious voice in my head was like having a long, comforting talk with an old friend. His retelling of the challenges of his first two and a half years, from the global financial crisis and the passage of Obamacare to the Democrats’ midterm collapse in 2010 and the successful operation to kill Osama bin Laden in May 2011, is full of revealing details and discerning insight.

But there’s a strange lacuna in A Promised Land, a missing thread that I kept looking for but never found. That thread is his popular base. To win his improbable bid for the presidency in 2008, Obama built his own powerful political army to beat Hillary Clinton, who had been building political support with her husband, President Bill Clinton, for decades. At its height, at the end of the 2008 election, Obama’s campaign had 13 million email addresses (20 percent of his vote total). Almost four million people had donated to him. Two million Obama supporters had created an account on My.BarackObama.com, the campaign’s social networking platform, which they used to organize 200,000 local events. Seventy thousand people used MyBO to create their own fundraising pages, which raised $30 million for his campaign.

But as is by now well known, once Obama entered office, he abandoned this army and staked his presidency on the inside-the-Beltway strategies of his first chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel. It’s never been clear to me that Obama had to drop this ball.

More here.

Bruno Latour | On Not Joining the Dots

‘As If By Magic: Selected Poems’, by Paula Meehan

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin at Dublin Review of Books:

A poem from Paula Meehan’s second collection, Pillow Talk (1994), is called “Autobiography”. Well, in some ways a Selected Poems is like an autobiography; it expresses a sense that the life lived to date, and the work done, have some weight and perhaps some unity. Also, all autobiographies are provisional, and a Selected does not have the terminal stamp of a Collected Poems. There may yet be – one hopes there will be – many surprises in store. But there are differences: the poems included in Paula Meehan’s Selected Poems do not tell the writer’s chronological story. Rather, many of them are revisitings of phases or moments in the poet’s life, from the varying perspectives of later days. They explore those enlightening moments, when new meanings emerge from well-remembered encounters, that may only come when there is a degree of distance, for example when the adult can see what the adults in her own earlier life were about, and divine the depths of their emotions.

A poem from Paula Meehan’s second collection, Pillow Talk (1994), is called “Autobiography”. Well, in some ways a Selected Poems is like an autobiography; it expresses a sense that the life lived to date, and the work done, have some weight and perhaps some unity. Also, all autobiographies are provisional, and a Selected does not have the terminal stamp of a Collected Poems. There may yet be – one hopes there will be – many surprises in store. But there are differences: the poems included in Paula Meehan’s Selected Poems do not tell the writer’s chronological story. Rather, many of them are revisitings of phases or moments in the poet’s life, from the varying perspectives of later days. They explore those enlightening moments, when new meanings emerge from well-remembered encounters, that may only come when there is a degree of distance, for example when the adult can see what the adults in her own earlier life were about, and divine the depths of their emotions.

more here.

Recovering Old Age

Joseph E. Davis and Paul Scherz at The New Atlantis:

At other times and in other places, traditional ways of life, social classification, and metaphysical order gave shape and coherence to the course of life, providing a picture of aging well. Each period of life had its activities, duties, and forms of flourishing.

At other times and in other places, traditional ways of life, social classification, and metaphysical order gave shape and coherence to the course of life, providing a picture of aging well. Each period of life had its activities, duties, and forms of flourishing.

The periods of aging, decline, and the approach of death were especially critical. They involve some of the most complex and unsettling aspects of human experience, and so the need for a strong community to provide direction and meaning is most acute. Many social and cultural practices, such as kinship cohorts, rites of generational transition, filial duties to ancestors, hierarchies that honor wisdom, social customs that guide in grieving, and arts of suffering and dying, provided support for this time of life.

more here.

What If You Could Do It All Over? The uncanny allure of our unlived lives.

Joshua Rothman in The New Yorker:

Once, in another life, I was a tech founder. It was the late nineties, when the Web was young, and everyone was trying to cash in on the dot-com boom. In college, two of my dorm mates and I discovered that we’d each started an Internet company in high school, and we merged them to form a single, teen-age megacorp. For around six hundred dollars a month, we rented office space in the basement of a building in town. We made Web sites and software for an early dating service, an insurance-claims-processing firm, and an online store where customers could “bargain” with a cartoon avatar for overstock goods. I lived large, spending the money I made on tuition, food, and a stereo.

Once, in another life, I was a tech founder. It was the late nineties, when the Web was young, and everyone was trying to cash in on the dot-com boom. In college, two of my dorm mates and I discovered that we’d each started an Internet company in high school, and we merged them to form a single, teen-age megacorp. For around six hundred dollars a month, we rented office space in the basement of a building in town. We made Web sites and software for an early dating service, an insurance-claims-processing firm, and an online store where customers could “bargain” with a cartoon avatar for overstock goods. I lived large, spending the money I made on tuition, food, and a stereo.

In 1999—our sophomore year—we hit it big. A company that wired mid-tier office buildings with high-speed Internet hired us to build a collaborative work environment for its customers: Slack, avant la lettre. It was a huge project, entrusted to a few college students through some combination of recklessness and charity. We were terrified that we’d taken on work we couldn’t handle but also felt that we were on track to create something innovative. We blew through deadlines and budgets until the C-suite demanded a demo, which we built. Newly confident, we hired our friends, and used our corporate AmEx to expense a “business dinner” at Nobu. Unlike other kids, who were what—socializing?—I had a business card that said “Creative Director.” After midnight, in our darkened office, I nestled my Aeron chair into my ikea desk, queued up Nine Inch Nails in Winamp, scrolled code, peeped pixels, and entered the matrix. After my client work was done, I’d write short stories for my creative-writing workshops. Often, I slept on the office futon, waking to plunder the vending machine next to the loading dock, where a homeless man lived with his cart.

I liked this entrepreneurial existence—its ambition, its scrappy, near-future velocity. I thought I might move to San Francisco and work in tech. I saw a path, an opening into life. But, as the dot-com bubble burst, our client’s business was acquired by a firm that was acquired by another firm that didn’t want what we’d made.

More here.

Friday Poem

Don Arturo Says:

When I was young

there was no difference

between the way I danced

and the way tomatoes

converted themselves

into sauce

I did the waltz or a

guaguancó

which everyone your rhythm

which every one your song

The whole town was caressed

to sleep with my two-tone

shoes

Everyone

had to leave me alone

on the dirt or on the wood

They used to come from afar

and near

just to look at Arturo

disappear.

by Victor Hernández Cruz

from After Atzlan

David R. Godine, publisher 1992

Scientists set a path for field trials of gene drive organisms

From Phys.Org:

Gene drive organisms (GDOs), developed with select traits that are genetically engineered to spread through a population, have the power to dramatically alter the way society develops solutions to a range of daunting health and environmental challenges, from controlling dengue fever and malaria to protecting crops against plant pests.

Gene drive organisms (GDOs), developed with select traits that are genetically engineered to spread through a population, have the power to dramatically alter the way society develops solutions to a range of daunting health and environmental challenges, from controlling dengue fever and malaria to protecting crops against plant pests.

But before these gene drive organisms move from the laboratory to testing in the field, scientists are proposing a course for responsible testing of this powerful technology. These issues are addressed in a new Policy Forum article on biotechnology governance, “Core commitments for field trials of gene drive organisms,” published Dec. 18, 2020 in Science by more than 40 researchers, including several University of California San Diego scientists.

“The research has progressed so rapidly with gene drive that we are now at a point when we really need to take a step back and think about the application of it and how it will impact humanity,” said Akbari, the senior author of the article and an associate professor in the UC San Diego Division of Biological Sciences. “The new commitments that address field trials are to ensure that the trials are safely implemented, transparent, publicly accountable and scientifically, politically and socially robust.”

More here.