by Liam Heneghan

In Memoriam Tim Robinson (1935 – 2020) and Máiréad Robinson (1934 – 2020)

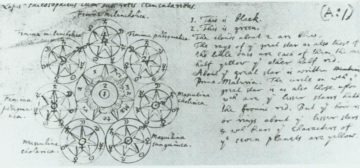

In Connemara: Listening to the Wind (2006), the first volume of cartographer and writer Tim Robinson’s trilogy of books about that rugged part of Co. Galway, Robinson records an illuminating and slightly fraught exchange that he had with landscape artist Richard Long about the fate of the artist’s work left exposed to the battering Irish coastal elements.

Work of Long’s include pieces sculpted from rocks and other materials found as he traversed natural landscapes on foot. The sculptures are gradually re-arranged by forces in the landscape, though the images have greater durability and are often displayed in galleries and preserved in archives.

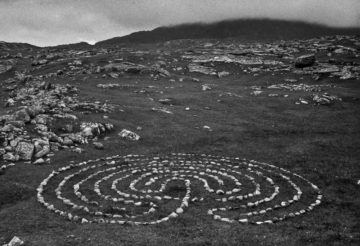

In his excursus about Connemara to complete his trilogy, Robinson located one of Long’s sculpture on a small headland near the town of Roundstone The piece, entitled Connemara Sculpture (1971), is comprised of beach pebbles arranged in a distinctive pattern. This was not the first of Long’s pieces that Robinson had located and mapped. As a gift for Long, Robinson’s wife Máiréad had sent Long a copy of a map on which Robinson had marked a couple of pieces on Inishmore, the largest of the Aran Islands.

Long took umbrage to the gift, writing to Robinson that he was “very surprised and aghast when someone told me years ago that my work was marked on a map.” It had not been his intention, he went on to write, for the sculptures “to be marked sites.” Long concludes his letter to Robinson noting that fortunately the “map that you kindly sent… didn’t have my sculpture on it.”

Robinson—that consummate map-maker—replied to Long, pointing out explicitly where these sculptures were marked on the map. Of course they were mapped!

Along with Robinson’s spirited defense of the fidelity of his mapmaking, he makes the following point: “…once the artist has made an intervention in the landscape and left it there, it contributes to other peoples experience of place, which may well be expressed in someone’s else work of art.” He goes on to write, “…your marks on the landscape will have a career of their own; they are no longer defined by their origin in your creativity.” Read more »

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.”

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.” Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

In May 1963, in a Kennedy family living room on Central Park South, Lorraine Hansberry tried to defend civil rights activists’ safety. The Raisin in the Sun playwright had come along with actor Harry Belafonte, author James Baldwin, and other luminaries at the invitation of Robert F. Kennedy and Baldwin. She listened as activist Jerome Smith tried to impress upon the attorney general the level of violence protesters were facing in the South. Smith had come straight from the Freedom Rides for medical treatment on his jaw and head, having been beaten in Birmingham.

In May 1963, in a Kennedy family living room on Central Park South, Lorraine Hansberry tried to defend civil rights activists’ safety. The Raisin in the Sun playwright had come along with actor Harry Belafonte, author James Baldwin, and other luminaries at the invitation of Robert F. Kennedy and Baldwin. She listened as activist Jerome Smith tried to impress upon the attorney general the level of violence protesters were facing in the South. Smith had come straight from the Freedom Rides for medical treatment on his jaw and head, having been beaten in Birmingham. Most of the alien civilizations that ever dotted our galaxy have probably killed themselves off already.

Most of the alien civilizations that ever dotted our galaxy have probably killed themselves off already.

Countless writers, with varying degrees of success, have reimagined the life of Jesus Christ. As my colleague

Countless writers, with varying degrees of success, have reimagined the life of Jesus Christ. As my colleague  On April 10, 1805, in honor of the Christian Holy Week, a German immigrant and conductor named

On April 10, 1805, in honor of the Christian Holy Week, a German immigrant and conductor named