Damian Carrington in The Guardian:

Cultured meat, produced in bioreactors without the slaughter of an animal, has been approved for sale by a regulatory authority for the first time. The development has been hailed as a landmark moment across the meat industry.

Cultured meat, produced in bioreactors without the slaughter of an animal, has been approved for sale by a regulatory authority for the first time. The development has been hailed as a landmark moment across the meat industry.

The “chicken bites”, produced by the US company Eat Just, have passed a safety review by the Singapore Food Agency and the approval could open the door to a future when all meat is produced without the killing of livestock, the company said.

Dozens of firms are developing cultivated chicken, beef and pork, with a view to slashing the impact of industrial livestock production on the climate and nature crises, as well as providing cleaner, drug-free and cruelty-free meat. Currently, about 130 million chickens are slaughtered every day for meat, and 4 million pigs. By weight, 60% of the mammals on earth are livestock, 36% are humans and only 4% are wild.

More here.

I should hate The Innovation Delusion. I’ve made a career as a futurist in Silicon Valley, helping big companies think about the business implications and commercial opportunities of emerging technologies. My father-in-law spent his career in the computer industry, my wife helps run her school’s “maker lab,” and my son graduated from

I should hate The Innovation Delusion. I’ve made a career as a futurist in Silicon Valley, helping big companies think about the business implications and commercial opportunities of emerging technologies. My father-in-law spent his career in the computer industry, my wife helps run her school’s “maker lab,” and my son graduated from  Since 2016, liberals have adopted a strategy of delegitimisation, condemning Mr Trump, and his supporters, for degrading political life. A grass-roots campaign of Democrats, Independents and Never-Trump conservatives, which describes itself as the “Resistance”, has also protested Mr Trump at every turn: over his treatment of women, the separation of immigrant families and his hostility towards Black Lives Matter.

Since 2016, liberals have adopted a strategy of delegitimisation, condemning Mr Trump, and his supporters, for degrading political life. A grass-roots campaign of Democrats, Independents and Never-Trump conservatives, which describes itself as the “Resistance”, has also protested Mr Trump at every turn: over his treatment of women, the separation of immigrant families and his hostility towards Black Lives Matter. I’

I’ The old net delusion was naïve but internally consistent. The new net delusion is fragmented and self-contradictory. It vacillates between radical pessimism about the effects of digital platforms and boosterism when new online happenings seem to revive the old cyber-utopian dreams.

The old net delusion was naïve but internally consistent. The new net delusion is fragmented and self-contradictory. It vacillates between radical pessimism about the effects of digital platforms and boosterism when new online happenings seem to revive the old cyber-utopian dreams. ‘Oh – Vivienne! Was there ever such a torture since life began!’ a dazed Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary in 1930 after a typically miserable visit from T S Eliot and his wife. Vivien had been paranoid and cryptic, rambling about hornets under her bed as Tom tried to cover up with ‘longwinded and facetious’ stories, as she wrote to Vanessa Bell. What agony ‘to bear her on ones shoulders,’ Woolf marvelled, ‘biting, wriggling, raving, scratching, unwholesome, powdered … This bag of ferrets is what Tom wears round his neck.’ To offset this grotesque picture, Ann Pasternak Slater provides a kinder but equally revealing image of the Eliots’ early married life together, supplied by their friend Brigit Patmore. While they were all in the chemist’s one day, Vivien, a keen dancer, decided to demonstrate a ballet move, holding onto the counter with one hand, rising on her toes and putting out her other hand, ‘which Tom took in his right hand, watching Vivien’s feet with ardent interest whilst he supported her with real tenderness … Most husbands would have said, “Not here, for Heaven’s sake!”’ It’s a brilliant snapshot of their marital pas de deux, Viv letting it all hang out, Tom enabling.

‘Oh – Vivienne! Was there ever such a torture since life began!’ a dazed Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary in 1930 after a typically miserable visit from T S Eliot and his wife. Vivien had been paranoid and cryptic, rambling about hornets under her bed as Tom tried to cover up with ‘longwinded and facetious’ stories, as she wrote to Vanessa Bell. What agony ‘to bear her on ones shoulders,’ Woolf marvelled, ‘biting, wriggling, raving, scratching, unwholesome, powdered … This bag of ferrets is what Tom wears round his neck.’ To offset this grotesque picture, Ann Pasternak Slater provides a kinder but equally revealing image of the Eliots’ early married life together, supplied by their friend Brigit Patmore. While they were all in the chemist’s one day, Vivien, a keen dancer, decided to demonstrate a ballet move, holding onto the counter with one hand, rising on her toes and putting out her other hand, ‘which Tom took in his right hand, watching Vivien’s feet with ardent interest whilst he supported her with real tenderness … Most husbands would have said, “Not here, for Heaven’s sake!”’ It’s a brilliant snapshot of their marital pas de deux, Viv letting it all hang out, Tom enabling. IT IS CUSTOMARY TO START an essay about Kafka by emphasizing how impossible it is to write about Kafka, then apologizing for making a doomed attempt. This gimmick has a distinguished lineage. “How, after all, does one dare, how can one presume?” Cynthia Ozick asks in the New Republic before she presumes for several ravishing pages. In the Paris Review, Joshua Cohen insists that “being asked to write about Kafka is like being asked to describe the Great Wall of China by someone who’s standing just next to it. The only honest thing to do is point.” But far from pointing, he gestures for thousands of words.

IT IS CUSTOMARY TO START an essay about Kafka by emphasizing how impossible it is to write about Kafka, then apologizing for making a doomed attempt. This gimmick has a distinguished lineage. “How, after all, does one dare, how can one presume?” Cynthia Ozick asks in the New Republic before she presumes for several ravishing pages. In the Paris Review, Joshua Cohen insists that “being asked to write about Kafka is like being asked to describe the Great Wall of China by someone who’s standing just next to it. The only honest thing to do is point.” But far from pointing, he gestures for thousands of words. Aristotle conceived of the world in terms of teleological “final causes”; Darwin, or so the story goes, erased purpose and meaning from the world, replacing them with a bloodless scientific algorithm. But should we abandon all talk of meanings and purposes, or instead conceptualize them as emergent rather than fundamental? Philosophers (and former Mindscape guests)

Aristotle conceived of the world in terms of teleological “final causes”; Darwin, or so the story goes, erased purpose and meaning from the world, replacing them with a bloodless scientific algorithm. But should we abandon all talk of meanings and purposes, or instead conceptualize them as emergent rather than fundamental? Philosophers (and former Mindscape guests)  In the first half of 2020, as the world economy shut down, hundreds of millions of people across the world lost their jobs. Following India’s lockdown on March 24, 10s of millions of displaced migrant workers thronged bus stops waiting for a ride back to their villages. Many gave up and spent weeks on the road walking home. Over 1.5 billion young people were

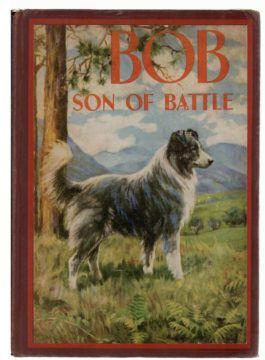

In the first half of 2020, as the world economy shut down, hundreds of millions of people across the world lost their jobs. Following India’s lockdown on March 24, 10s of millions of displaced migrant workers thronged bus stops waiting for a ride back to their villages. Many gave up and spent weeks on the road walking home. Over 1.5 billion young people were  The 1898 children’s classic known in America as Bob, Son of Battle and in England as Owd Bob: The Grey Dog of Kenmuir, by Alfred Ollivant, was long declared—and still is considered, by some—one of the great dog stories of all time, if not the greatest. One reviewer, E.V. Lucas, writing in The Northern Counties Magazine soon after the book was published, felt that this was the first time “full justice” had been done to a dog as a character in fiction. He declared, “Owd Bob is more than a dog story; it is a dog epic.”

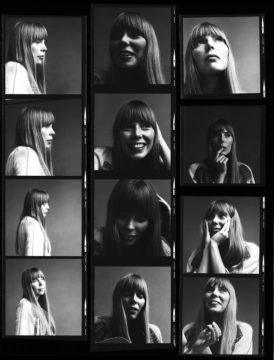

The 1898 children’s classic known in America as Bob, Son of Battle and in England as Owd Bob: The Grey Dog of Kenmuir, by Alfred Ollivant, was long declared—and still is considered, by some—one of the great dog stories of all time, if not the greatest. One reviewer, E.V. Lucas, writing in The Northern Counties Magazine soon after the book was published, felt that this was the first time “full justice” had been done to a dog as a character in fiction. He declared, “Owd Bob is more than a dog story; it is a dog epic.” In 1964, a twenty-year-old Canadian singer named Joan Anderson began composing her own folk songs. They were good folk songs, sturdily constructed and memorable, but the genre corseted her. She would need to roam the mountains and plains of rock and jazz in order to claim her gift. Folk was not enough—but it was what was available to her as a young woman from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in the early nineteen-sixties, a woman in possession of an ethereal soprano and a four-string baritone ukulele, the instrument she could afford to buy on her own after her mother nixed a guitar. At nineteen, she left home for art school in Alberta—painting was her first creative outlet—and then began touring, playing in coffeehouses or church basements in Toronto and Calgary and Detroit. For her mother Myrtle’s birthday in 1965, Joan made her a tape with three of the songs she had written, “Urge for Going,” “Born to Take the Highway,” and “Here Today and Gone Tomorrow.” In the folk tradition, they celebrate footloose rambling.

In 1964, a twenty-year-old Canadian singer named Joan Anderson began composing her own folk songs. They were good folk songs, sturdily constructed and memorable, but the genre corseted her. She would need to roam the mountains and plains of rock and jazz in order to claim her gift. Folk was not enough—but it was what was available to her as a young woman from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in the early nineteen-sixties, a woman in possession of an ethereal soprano and a four-string baritone ukulele, the instrument she could afford to buy on her own after her mother nixed a guitar. At nineteen, she left home for art school in Alberta—painting was her first creative outlet—and then began touring, playing in coffeehouses or church basements in Toronto and Calgary and Detroit. For her mother Myrtle’s birthday in 1965, Joan made her a tape with three of the songs she had written, “Urge for Going,” “Born to Take the Highway,” and “Here Today and Gone Tomorrow.” In the folk tradition, they celebrate footloose rambling.