Month: December 2020

Peter Singer and Agata Sagan: What Is Your Moral Plan for 2021?

Peter Singer and Agata Sagan in Project Syndicate:

Many people make New Year’s resolutions. The most common ones, at least in the United States, are to exercise more, eat healthier, save money, lose weight, or reduce stress. Some may resolve to be better to a particular person – not to criticize their partner, to visit their aging grandmother more often, or to be a better friend to someone close to them. Yet few people – just 12%, according to one US study – resolve to become a better person in general, meaning better in a moral sense.

Many people make New Year’s resolutions. The most common ones, at least in the United States, are to exercise more, eat healthier, save money, lose weight, or reduce stress. Some may resolve to be better to a particular person – not to criticize their partner, to visit their aging grandmother more often, or to be a better friend to someone close to them. Yet few people – just 12%, according to one US study – resolve to become a better person in general, meaning better in a moral sense.

One possible explanation is that most people focus on their own well-being, and don’t see being morally better as something that is in their own interest. A more charitable explanation is that many people see morality as a matter of conforming to a set of rules establishing the things we should not do.

That is not very surprising in societies built on the Jewish and Christian traditions, in which the Ten Commandments are held up as the core of morality. But, today, traditional moral rules have only limited relevance to ordinary life. Few of us are ever in situations in which killing someone even crosses our mind. Most of us don’t need to steal, and to do so is not a great temptation – most people will even return a lost wallet with money in it.

More here.

That time physicist John Wheeler left classified H-bomb documents on a train

Jennifer Ouellette in Ars Technica:

In the popular science world, physicist John Wheeler is probably best known for popularizing the term “black hole,” although his research spanned a broad range of fields, including relativity, quantum theory, and nuclear fission. He also worked on Project Matterhorn B in the early 1950s, the controversial US effort to develop a hydrogen bomb. In January 1953, Wheeler accidentally left a highly classified document concerning that program on a train as he traveled from his Princeton, New Jersey home to Washington, DC. It was a stereotypical “absent-minded professor” moment, and one with significant national security implications.

In the popular science world, physicist John Wheeler is probably best known for popularizing the term “black hole,” although his research spanned a broad range of fields, including relativity, quantum theory, and nuclear fission. He also worked on Project Matterhorn B in the early 1950s, the controversial US effort to develop a hydrogen bomb. In January 1953, Wheeler accidentally left a highly classified document concerning that program on a train as he traveled from his Princeton, New Jersey home to Washington, DC. It was a stereotypical “absent-minded professor” moment, and one with significant national security implications.

More here.

My 3-year-old was handling the pandemic well, then his mom was diagnosed with cancer

Zia Ahmed in the Washington Post:

Our family had been fortunate. Ali was too young for school. Anna’s job allowed her to telework during the pandemic. Unlike many parents, we didn’t have to worry about money or child care. Our little boy adapted well to social isolation. He read, played catch and helped me cook. We explored local parks and ponds, avoiding people and chasing ducks.

Our family had been fortunate. Ali was too young for school. Anna’s job allowed her to telework during the pandemic. Unlike many parents, we didn’t have to worry about money or child care. Our little boy adapted well to social isolation. He read, played catch and helped me cook. We explored local parks and ponds, avoiding people and chasing ducks.

But as a wise Englishman once noted, it’s always just when a fellow is feeling particularly braced that fate sneaks up behind him with the bit of lead piping.

After Anna found the lump, I came to resent words I’d associated with other people who were older: mammogram, ultrasound, biopsy. At each step, our fears ballooned, until that calamitous afternoon when the doctor confirmed the worst.

More here.

Bruno Latour – A Shift in Agency – With Apologies to David Hume

Revisiting the Short Career of Breece D’J Pancake

Justin Taylor at Bookforum:

Pancake’s depictions of the culture and geography of Appalachia and the Trans-Allegheny were all but unprecedented. The hills and hollows of West Virginia were largely neglected in American literature, even the intensely regionalist literatures of the South, possibly because West Virginia had fought with the Union during the Civil War, and so had little to contribute to the revisionist horseshit of Lost Cause sentimentality. Pancake seems to know everything about this place, from its hilltops to its coal mines to its barrooms, and he has an eye for the small, sharp details that bring it to life. In “Hollow,” when Buddy wakes up on the floor of his trailer after a night of drinking and brawling, there is “a little ball of rayon batting against his nostril as he breathed.” Bo, in “Fox Hunters,” “stepped onto the pavement feeling tired and moved a few paces until headlights flooded his path, showing up the highway steam and making the road give birth to little ghosts beneath his feet.” At the same time, Pancake is always attentive to the natural world. He finds a kind of holiness in the history-dwarfing scale of geologic time.

Pancake’s depictions of the culture and geography of Appalachia and the Trans-Allegheny were all but unprecedented. The hills and hollows of West Virginia were largely neglected in American literature, even the intensely regionalist literatures of the South, possibly because West Virginia had fought with the Union during the Civil War, and so had little to contribute to the revisionist horseshit of Lost Cause sentimentality. Pancake seems to know everything about this place, from its hilltops to its coal mines to its barrooms, and he has an eye for the small, sharp details that bring it to life. In “Hollow,” when Buddy wakes up on the floor of his trailer after a night of drinking and brawling, there is “a little ball of rayon batting against his nostril as he breathed.” Bo, in “Fox Hunters,” “stepped onto the pavement feeling tired and moved a few paces until headlights flooded his path, showing up the highway steam and making the road give birth to little ghosts beneath his feet.” At the same time, Pancake is always attentive to the natural world. He finds a kind of holiness in the history-dwarfing scale of geologic time.

more here.

On Dreams and Literature

Ed Simon at The Millions:

Both The Divine Comedy and Piers Plowman express verities accessed by the mind in repose; Langland’s poem, for not beginning in a dark wood but rather in a sunny field, embodies mystical apprehensions as surely as does Dante. A key difference is that Langland’s allegory is so obvious (as anyone who has seen the medieval play Everyman can attest is true of the period). Characters named after the Seven Deadly Sins, or called Patience, Clergy, and Scripture (and Old Age, Death, and Pestilence) all interact with Will — whose name has its own obvious implications. By contrast, Dante’s characters bear a resemblance to actual people (or they are actual people, from Aristotle in Limbo to Thomas Aquinas in Heaven), even while the events depicted are seemingly more fantastic (though in Piers Plowman Will witness both the fall of man and the harrowing of hell). Both are, however, written in the substance of dreams. Forget the didactic obviousness of allegory, the literal cipher that defines that form, and believe that in a field between Worcestershire and Hertfordshire Will did plumb the mysteries of eternity while sleeping. What makes the dream vision a chimerical form is that maybe he did. That’s the thing with dreams and their visions; there is no need to suspend disbelief. We’re not in the realm of fantasy or myth, for in dreams order has been abolished, anything is possible, and nothing is prohibited, not even flouting the arid rules of logic.

Both The Divine Comedy and Piers Plowman express verities accessed by the mind in repose; Langland’s poem, for not beginning in a dark wood but rather in a sunny field, embodies mystical apprehensions as surely as does Dante. A key difference is that Langland’s allegory is so obvious (as anyone who has seen the medieval play Everyman can attest is true of the period). Characters named after the Seven Deadly Sins, or called Patience, Clergy, and Scripture (and Old Age, Death, and Pestilence) all interact with Will — whose name has its own obvious implications. By contrast, Dante’s characters bear a resemblance to actual people (or they are actual people, from Aristotle in Limbo to Thomas Aquinas in Heaven), even while the events depicted are seemingly more fantastic (though in Piers Plowman Will witness both the fall of man and the harrowing of hell). Both are, however, written in the substance of dreams. Forget the didactic obviousness of allegory, the literal cipher that defines that form, and believe that in a field between Worcestershire and Hertfordshire Will did plumb the mysteries of eternity while sleeping. What makes the dream vision a chimerical form is that maybe he did. That’s the thing with dreams and their visions; there is no need to suspend disbelief. We’re not in the realm of fantasy or myth, for in dreams order has been abolished, anything is possible, and nothing is prohibited, not even flouting the arid rules of logic.

more here.

Thursday Poem

Burning the Old Year

Letters swallow themselves in seconds

Notes friends tied to the doorknob,

transparent scarlet paper,

sizzle like moth wings,

marry the air.

So much of any year is flammable,

lists of vegetables, partial poems.

Orange swirling flame of days,

so little is a stone.

Where there was something and suddenly isn’t,

an absence shouts, celebrates, leaves a space.

I begin again with the smallest numbers.

Quick dance, shuffle of losses and leaves,

only the things I didn’t do

crackle after the blazing dies.

by Naomi Shihab Nye,

from Words Under the Words: Selected Poems

Far Corner Books, 1995

Our Year in Hell

Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker:

What tone can one possibly strike for an overview of 2020? The Queen’s old label of annus horribilis for her own most troubled time hardly seems adequate. Even the right point of view is hard to decide on. Does it make more sense to see the year from high above, taking a picture of an entire panicked planet, or to start from the ant’s- or worm’s-eye view, with the transformation of our manners and minds by the strangeness of 2020 (and by its sadness, too)? Begin with the scale of the misery and dislocation? Narrow down to the specific sensory strangeness of the year?

What tone can one possibly strike for an overview of 2020? The Queen’s old label of annus horribilis for her own most troubled time hardly seems adequate. Even the right point of view is hard to decide on. Does it make more sense to see the year from high above, taking a picture of an entire panicked planet, or to start from the ant’s- or worm’s-eye view, with the transformation of our manners and minds by the strangeness of 2020 (and by its sadness, too)? Begin with the scale of the misery and dislocation? Narrow down to the specific sensory strangeness of the year?

Seeing the scale first is useful because it’s so unparalleled: not one city, or even one country, but everywhere at once. Paris shut down and the first silent nights in its history enforced, with Parisians carrying permission slips like schoolchildren just to go to a pharmacy. London under lockdown, Times Square in quarantine, dressed in ghost-town array. “A quiet capital is a contradiction in terms,” the great Max Beerbohm wrote during the London bombing. “It is a thing uncanny, spectral.” And yet, uncanny though it might be, the imagery of an actual pandemic is, truth be told, considerably less melodramatic than the cinematic version. Often, when we call something “unimaginable,” what we really mean is more like “too oft imagined.” We actually have been here before, in every pandemic movie, in that Will Smith one with the zombies, for instance—and, in the zombie movie, the people are slavering in the streets. In the real one, the streets are merely empty.

The sensory specifics are all that usually matter, or linger, in history. Read Daniel Defoe on the mid-seventeenth-century plague in London, and it is the inventory of specific people and places—how the bear-baiting pits got shut down—that is most memorable. Let’s mark down some new sensory experiences, which our descendants might find hard to credit.

More here.

Nearly a Century Later, We’re Still Reading — and Changing Our Minds About — Gatsby

Parul Sehgal in The New York Times:

One of the pleasures of writing about a book as widely read as “The Great Gatsby” is jetting through the obligatory plot summary. You recall Nick Carraway, our narrator, who moves next door to the mysteriously wealthy Jay Gatsby on Long Island. Gatsby, it turns out, is pining for Nick’s cousin, Daisy; his glittering life is a lure to impress her, win her back. Daisy is inconveniently married to the brutish Tom Buchanan, who, in turn, is carrying on with a married woman, the doomed Myrtle. Cue the parties, the affairs, Nick getting very queasy about it all. In a lurid climax, Myrtle is run over by a car driven by Daisy. Gatsby is blamed; Myrtle’s husband shoots him dead in his pool and kills himself. The Buchanans discreetly leave town, their hands clean. Nick is writing the book, we understand, two years later, in a frenzy of disgust.

One of the pleasures of writing about a book as widely read as “The Great Gatsby” is jetting through the obligatory plot summary. You recall Nick Carraway, our narrator, who moves next door to the mysteriously wealthy Jay Gatsby on Long Island. Gatsby, it turns out, is pining for Nick’s cousin, Daisy; his glittering life is a lure to impress her, win her back. Daisy is inconveniently married to the brutish Tom Buchanan, who, in turn, is carrying on with a married woman, the doomed Myrtle. Cue the parties, the affairs, Nick getting very queasy about it all. In a lurid climax, Myrtle is run over by a car driven by Daisy. Gatsby is blamed; Myrtle’s husband shoots him dead in his pool and kills himself. The Buchanans discreetly leave town, their hands clean. Nick is writing the book, we understand, two years later, in a frenzy of disgust.

Fitzgerald was proud of what he had achieved. “I think my novel is about the best American novel ever written,” he crowed. The book baffled reviewers, however, and sold poorly. “Of all the reviews, even the most enthusiastic, not one had the slightest idea what the book was about,” Fitzgerald wrote to the critic Edmund Wilson. That matter remains unsettled. The book has been treated as a beautiful bauble, fundamentally unserious. In a 1984 essay in The Times, John Kenneth Galbraith sniffed that Fitzgerald was only superficially interested in class. “It is the lives of the rich — their enjoyments, agonies and putative insanity — that attract his interest,” he wrote. “Their social and political consequences escape him as he himself escaped such matters in his own life.”

This interpretation has been turned on its head. Both new editions make light of the book’s beauty — it’s the treatment of the grotesque that is so compelling (Morris compares the characters to the “Real Housewives”). Both make the case that the book’s value lies in its critique of capitalism. Lee describes Fitzgerald as “a fan of Karl Marx,” and writes that “Gatsby” remains “a modern novel by exploring the intersection of social hierarchy, white femininity, white male love and unfettered capitalism.” For Morris, too, there is no romance between Gatsby and Daisy but “capitalism as an emotion”: “Gatsby meets Daisy when he’s a broke soldier, senses that she requires more prosperity, so five years later he returns as almost a parody of it. So the tragedy here is the death of the heart.”

More here.

Amit Chaudhuri on Satyajit Ray’s very Indian modernity

Amit Chaudhuri in Scroll.in:

It seems that there are all kinds of unresolved problems to do with Satyajit Ray – to do with thinking about him, with finding a language to speak about him that does not repeat the indubitable truisms about his humanism and lyricism. How does he fit into history, and into which history – the history of India; the history of filmmaking; some other – do we place him first?

It seems that there are all kinds of unresolved problems to do with Satyajit Ray – to do with thinking about him, with finding a language to speak about him that does not repeat the indubitable truisms about his humanism and lyricism. How does he fit into history, and into which history – the history of India; the history of filmmaking; some other – do we place him first?

We do not ordinarily talk about Ray “fitting in”, because he is an icon and a figurehead, and figureheads do not generally have to fit in. Traditions, schools, and oeuvres emanate from them. Glancing toward Ray, we see, indeed, the precious oeuvre, but it’s more difficult to trace the tradition – either leading up to Ray or emerging from him.

People closer to home will mention something called the “Bengal Renaissance” and Tagore when thinking of lineage. Even those who are not students of film know who some of the precursors are: Jean Renoir, Vittoria de Sica and John Ford. As to inheritors of the style, you could, with some hesitation and prudence, point to Adoor Gopalakrishnan, and, a bit further away, to Abbas Kiarostami. But what does this constellation of names and categories add up to?

More here.

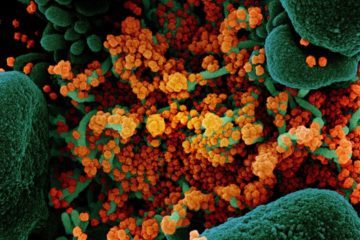

Covid-19 and a Data Detective Story

Nilotpal Chakravarti at his own Medium page:

The population density of Africa is low overall, with its population being about the same as that of India, while its area is ten times larger. But Nigeria’s population density is fairly high, in fact higher than that of Italy. And its largest city, Lagos, a dense megalopolis of 20 million people living cheek by jowl, is just the kind of city where Covid-19 may be expected to spread fast.

The population density of Africa is low overall, with its population being about the same as that of India, while its area is ten times larger. But Nigeria’s population density is fairly high, in fact higher than that of Italy. And its largest city, Lagos, a dense megalopolis of 20 million people living cheek by jowl, is just the kind of city where Covid-19 may be expected to spread fast.

All in all, Nigeria seems to have the makings of a Covid-19 disaster.

Yet data suggests that it is anything but. New Zealand and South Korea are generally both counted among the countries which have mounted the most successful Coronavirus responses. The Covid-19 death rate in Nigeria is about 6 per million, just above that of New Zealand and less than South Korea’s.

What explains Nigeria’s success? Is the Nigerian story too good to be true?

More here.

Inequality, class and the culture wars

Kenan Malik in Pandaemonium:

‘Woke orthodoxy abolished”; “a landmark speech”; “a counter-revolution”. One couldn’t miss the fawning from certain sections of the media. Whoever is responsible for equalities minister Liz Truss’s spin definitely deserves their Christmas bonus.

‘Woke orthodoxy abolished”; “a landmark speech”; “a counter-revolution”. One couldn’t miss the fawning from certain sections of the media. Whoever is responsible for equalities minister Liz Truss’s spin definitely deserves their Christmas bonus.

Truss, who doubles up as the international trade secretary, gave a speech on Thursday to the Centre for Policy Studies that promised to “reject the approach taken by the left, captured as they are by identity politics and loud lobby groups”, to dump fashionable “postmodernist philosophy – pioneered by Foucault” and, instead, to “root the equality debate in the real concerns people face”.

Take away the culture-war rhetoric and the anti-woke bombast, however, and there was little that moved beyond the bland. “It is not right,” she said, “that having a particular surname or accent can sometimes make it harder to get a job.” It is “appalling that pregnant women suffer discrimination at work” and that they have to “dress in a certain way to get ahead”. That “employers overlook the capabilities of people with disabilities”. And “outrageous… that LGBT people still face harassment”. No mainstream politician of the past 25 years would have disagreed. Though, if someone on the left had said all that, they would probably have been denounced for pursuing “woke orthodoxy” by the same voices now lauding Truss’s counter-revolution.

Truss dressed it all up as a demonstration of “conservative values”. What it actually revealed was the degree to which liberal orthodoxies have become accepted in Britain, including by conservatives.

More here.

Sabine Hossenfelder: How to talk like a physicist

Wednesday Poem

Once in Twelve Years, I Go to Church

I go to the church with the cross in it

and I kneel, because it hurts too much to sit,

and I pray, wordlessly. I go when it’s quiet,

when service is over, ideally when no one

is there. But someone is always there.

I don’t mean the priest. I don’t mean Jesus

or some deity who looks down on us.

God does not look down on us.

God does not exist, and yet God is

all there is. I mean I look at these walls,

mammoth two-foot by four-foot

blocks of limestone that could crush us,

beautifully. And I recall that limestone

is composed entirely of skeletal fragments,

of organisms caught in their less-than-final

resting places. And I hear in the stone

a rustling, the rustling of creatures

who once crept and bled upon the Earth,

like you and me. Creatures still here,

still whispering in our ears, still embodied

and participating in the language of the world.

What I hear is: that word—upon—is wrong.

We say upon as if the Earth were merely

lithosphere—the ground beneath—

and not the atmosphere, the Ecosphere:

not the sky and why above, not the blood

and good within. We say upon as if

the Earth and men were not each other,

and the lesser was merely a visitor

upon the greater’s soil. We say upon

but mean as one, we mean the Earth

rose up and lived as us, as she lives

the creatures who whisper in these walls,

and as she lives the little poet

turning to limestone in this poem.

by Ricky Ray

from Ecotheo Review

The Next Big Challenge: Trump-Proofing the Presidency

John Cassidy in The New Yorker:

With just three weeks left until the Inauguration of Joe Biden, the end of Donald Trump’s Presidency is firmly in sight. Trump, despite having finally backed down and signed the covid-19 relief bill, will surely look to cause more mayhem before he leaves office. Over the weekend, he urged his followers, via Twitter, to protest in Washington on January 6th, the day that the new Congress is scheduled to ratify the results of the Electoral College.

With just three weeks left until the Inauguration of Joe Biden, the end of Donald Trump’s Presidency is firmly in sight. Trump, despite having finally backed down and signed the covid-19 relief bill, will surely look to cause more mayhem before he leaves office. Over the weekend, he urged his followers, via Twitter, to protest in Washington on January 6th, the day that the new Congress is scheduled to ratify the results of the Electoral College.

Trump’s departure will prompt cries of relief in many parts of the country, but there is now vital work to be done. The past four years have taught us that the American system of government is no match for a President who, like Trump, will not hesitate to break long-established rules and norms. During his four years in office, the forty-fifth President has lied on a daily basis; purged officials who challenged him; used his vast social-media following to intimidate other elected Republicans; charged the federal government millions of dollars for the use of his private businesses; awarded prominent positions to his family members; pardoned some of his closest political allies; and, finally, tried to overturn a perfectly legitimate election. Conceivably, he could run for office again in four years. What can be done to Trump-proof the Presidency against him or an acolyte?

One seemingly obvious reform is to change the voting system to prevent another demagogue from taking power despite losing the popular vote.

More here.

A review of 2020 through Nature’s editorials

From Nature:

Editorials represent Nature’s collective voice on the week’s news, providing a commentary on a range of topics, from research discoveries to major world events involving science. And although 2020 has been dominated by just one topic, we’ve aimed to stay on top of other important developments, too.

Editorials represent Nature’s collective voice on the week’s news, providing a commentary on a range of topics, from research discoveries to major world events involving science. And although 2020 has been dominated by just one topic, we’ve aimed to stay on top of other important developments, too.

January: environmental ‘super-year’ ahead

Nature’s first editorial of 2020 marked the beginning of what was expected to be a super-year for the environment and sustainable development, with world leaders poised to meet to update their commitments in these areas. Most of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which were established by the United Nations in 2015, were not on track even before the coronavirus pandemic, and global targets to tackle climate change and reduce biodiversity loss were also behind schedule. We urged nations to consider mandatory reporting of their progress towards the SDGs, as most do for economic data. Research published in Nature from a joint US–China team provided the outlines for such a reporting framework1.

More here.

Bruno Latour: Natural Religion as a Pleonasm

A Cosmos Full of Life-Generating Goo

It’s important to see the full opportunity waiting ahead. Each planet or moon is its own world, with its own history and story to tell, and its own potential (however one might define this) for the future. Though mostly barren of life, they are far from empty; many are chock-full of the materials that would go into life-generating goo: sugars, amino acids, carboxylic acids and powerful molecules that drive reactions away from equilibrium. On bodies where widespread life might not be possible, many of them nevertheless contain microniches where life can take root and flourish for billions of years. Conceivably, for every planet that crossed the threshold of biogenesis, there were scores more that came part or even most of the way that just missed the nudge to do so.

It’s important to see the full opportunity waiting ahead. Each planet or moon is its own world, with its own history and story to tell, and its own potential (however one might define this) for the future. Though mostly barren of life, they are far from empty; many are chock-full of the materials that would go into life-generating goo: sugars, amino acids, carboxylic acids and powerful molecules that drive reactions away from equilibrium. On bodies where widespread life might not be possible, many of them nevertheless contain microniches where life can take root and flourish for billions of years. Conceivably, for every planet that crossed the threshold of biogenesis, there were scores more that came part or even most of the way that just missed the nudge to do so.

more here.

The Books of Nathalie Léger

Exposition, Suite for Barbara Loden, and The White Dress are literary works of research. Léger is the Director of the Institut Mémoires de l’Édition Contemporaine (Institute for Contemporary Publishing Archives), so it is unsurprising that archives and the figure of the archive should feature in her work. What is perhaps more notable is the way in which Léger sees the archive as a literary space. In a 2014 interview, in the French journal La Cause du Désir, Léger describes the archive as ‘a field of interpretation’ and therefore also ‘one of the favourite places of fiction’. (These are my translations of Léger’s responses. The original interview is here.) Of the astonishing object sometimes found in the archive, ‘if it contains information, it also contains a strong emotional charge…To speak that part of the real, to give it thanks and undo its hold, there is only literature’. As the constant return to the story of the author’s mother illustrates, the ‘strong emotional charge’ of an object can be one of unexpected, or buried, connections.

Exposition, Suite for Barbara Loden, and The White Dress are literary works of research. Léger is the Director of the Institut Mémoires de l’Édition Contemporaine (Institute for Contemporary Publishing Archives), so it is unsurprising that archives and the figure of the archive should feature in her work. What is perhaps more notable is the way in which Léger sees the archive as a literary space. In a 2014 interview, in the French journal La Cause du Désir, Léger describes the archive as ‘a field of interpretation’ and therefore also ‘one of the favourite places of fiction’. (These are my translations of Léger’s responses. The original interview is here.) Of the astonishing object sometimes found in the archive, ‘if it contains information, it also contains a strong emotional charge…To speak that part of the real, to give it thanks and undo its hold, there is only literature’. As the constant return to the story of the author’s mother illustrates, the ‘strong emotional charge’ of an object can be one of unexpected, or buried, connections.

more here.