A specimen of the Peruvian grasshopper Lophacris cristata mounted in a vitrine. Photo taken in my living room in December of 2020.

Month: December 2020

Movies of the Mind

by Brooks Riley

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

Where did this come from, this semi-androgenous role so foreign to my timid female self? I may have been feeling powerless back then, on the verge of puberty and alone in my ignorance. My daydream could just as easily have come from a twelve-year-old boy but more likely it incubated in the tomboy I sometimes was. Gender had little to do with it, though. Empowerment is what mattered, something I desperately needed, as well as a jolly exciting way to pass the time until I fell asleep.

Daydreams have served the needs of human beings since the evolution of the imagination a few million years ago. The caveman who dreamed of bagging a boar pictured an encounter in his mind and practiced his moves. Except for those with aphantasia, we can all visualize places we’ve been and people we’ve seen. This ‘inner eye’ allows us to do much more than that—to create people and places that we’ve never seen, that don’t exist, and to give them life, context, and raisons d’être. This is how fiction is born, before the first word has even hit the page.

We all indulge in daydreams, those reticules in the mind that hold our most vivid hopes in the form of mise-en-scène, endowing our bucket list with emotional nuance and narrative—however improbable the reality. With age, however, imagining a dazzling future no longer seems viable, as the scope of our hopes and desires shrink, like the law of diminishing returns. Daydreaming is eventually reduced to hardly more than an imagined walk in the park when you’re stuck at home. Much of my bucket list has been accomplished, in sometimes surprising ways. My life has been eclectic, peripatetic, unexpected, and gratifying. I’ve been places, done things. What more could there be to dream about? Read more »

Early Years in Arizona

by Hari Balasubramanian

This year marks two decades since I moved from India to the United States. I look back at how it all began in Arizona.

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow.

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow.

So in August 2000, I found myself traveling across continents to this powerful country that I knew little about. It was my first ever time outside India and my first ever flight. From Chennai, I flew to Kuala Lumpur, then, after an eight-hour layover which I didn’t mind at all, to Los Angeles and finally, after the worry of a missed connection, to Phoenix, Arizona. The gleaming, modern airports, the meals and the movies, the turbulence and the clouds: it was all very exciting, a glimpse of an elite world that had once seemed inaccessible.

At the Phoenix airport, someone from the Indian Students Association at ASU came to pick me up. After what seemed like a recklessly fast drive – in fact it was normal: it’s just that I’d never experienced a 70-miles-an-hour ride on a highway before – he dropped me off at an apartment shared by three Indian grad students. One of them, my host until I found an apartment, wore a veshti, the wraparound skirt common in south India. He spoke Tamil fluently; he spoke it so well that I could well have been in my home state. I had a nagging suspicion at the time that people might change as soon as they landed in a foreign country – that they might change their attire, even forget their mother tongue. It was reassuring to know that wasn’t true. At the heart of such doubts, I see now, was a fear that I would quickly surrender my Indianness. Read more »

When fabulous clothes are outlawed, only outlaws will be fabulous

Virginia Postrel with an excerpt from her book The Fabric of Civilization, in Reason:

Anyone who has been a teenager or dressed a 4-year-old knows that what we wear can be a source of intense conflict. Clothing is more than essential protection against the elements. It helps define who we are—to the world and to ourselves. And it is an everyday source of aesthetic pleasure. Clothing is a form of self-expression.

Anyone who has been a teenager or dressed a 4-year-old knows that what we wear can be a source of intense conflict. Clothing is more than essential protection against the elements. It helps define who we are—to the world and to ourselves. And it is an everyday source of aesthetic pleasure. Clothing is a form of self-expression.

For most of human history, most people simply couldn’t afford choice in clothing. Cloth was too expensive. But there were exceptions, particularly in the thriving commercial cities of Europe and Asia in the Middle Ages, much of whose prosperity was itself derived from the textile trade. Peasants might still have to stick to basics, but merchants and the artisans who served them could afford more. With commercial prosperity came choice, and with it an unsettling social dynamism that expressed itself in clothing.

In response, rulers adopted sumptuary codes that restricted what people could wear. The exact nature of those codes varied with the local culture—and so did the ways in which consumers resisted. Because they almost always did.

More here.

Over the past two years, astronomers have rewritten the story of our galaxy

Charlie Wood in Quanta:

When the Khoisan hunter-gatherers of sub-Saharan Africa gazed upon the meandering trail of stars and dust that split the night sky, they saw the embers of a campfire. Polynesian sailors perceived a cloud-eating shark. The ancient Greeks saw a stream of milk, gala, which would eventually give rise to the modern term “galaxy.”

When the Khoisan hunter-gatherers of sub-Saharan Africa gazed upon the meandering trail of stars and dust that split the night sky, they saw the embers of a campfire. Polynesian sailors perceived a cloud-eating shark. The ancient Greeks saw a stream of milk, gala, which would eventually give rise to the modern term “galaxy.”

In the 20th century, astronomers discovered that our silver river is just one piece of a vast island of stars, and they penned their own galactic origin story. In the simplest telling, it held that our Milky Way galaxy came together nearly 14 billion years ago when enormous clouds of gas and dust coalesced under the force of gravity. Over time, two structures emerged: first, a vast spherical “halo,” and later, a dense, bright disk. Billions of years after that, our own solar system spun into being inside this disk, so that when we look out at night, we see spilt milk — an edge-on view of the disk splashed across the sky.

Yet over the past two years, researchers have rewritten nearly every major chapter of the galaxy’s history. What happened? They got better data.

More here.

Archaeologists uncover ancient street food shop in Pompeii

Philip Pullella at Reuters:

Archaeologists in Pompeii, the city buried in a volcanic eruption in 79 AD, have made the extraordinary find of a frescoed hot food and drinks shop that served up the ancient equivalent of street food to Roman passersby.

Archaeologists in Pompeii, the city buried in a volcanic eruption in 79 AD, have made the extraordinary find of a frescoed hot food and drinks shop that served up the ancient equivalent of street food to Roman passersby.

Known as a termopolium, Latin for hot drinks counter, the shop was discovered in the archaeological park’s Regio V site, which is not yet open the public, and unveiled on Saturday.

Traces of nearly 2,000-year-old food were found in some of the deep terra cotta jars containing hot food which the shop keeper lowered into a counter with circular holes.

The front of the counter was decorated with brightly coloured frescoes, some depicting animals that were part of the ingredients in the food sold, such as a chicken and two ducks hanging upside down.

More here.

Jingle Bells, In Different Persian Scales and Rhythms

Sunday Poem

“Reflections do, in truth, reflect”

……………… —Soiléir Scáthán

During Donald Trump’s Inauguration

I closed my eyes, to conjure from the 1950’s

An image of that towering man Paul Robeson

Singing his heart and soul across the border

Between Washington State and Canada

When tides of race and power and wealth

Surged all as one to try to drown him out,

Snatching his passport lest his songs be heard

By the Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers Union.

I conjured the noisy flatback truck maneuvered

To the border, and the straining loudspeakers

Bearing the resonant burden to where his masters

Feared to grant him passage. And I conjured

All those gathered thousands rising to Joe Hill,

To Ol’ Man River and to Let My People Go, rising

To anthems that might undermine frontiers.

This still I hoard: that profound voice rolling

Across the barriers built by poisoned money,

Vibrant with the urge to make America good.

by Paddy Bushe

from: Waxwing, 2017

“The Age of Innocence” at a Moment of Increased Appetite for Eating the Rich

Hillary Kelly in The New Yorker:

When she began writing “The Age of Innocence,” in September, 1919, Edith Wharton needed a best-seller. The economic ravages of the First World War had cut her annual income by about sixty per cent. She’d recently bought and begun to renovate a country house, Pavillon Colombe, in Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt, where she installed new black-and-white marble floors in the dining room, replaced a “humpy” lawn with seven acres of lavish gardens, built a water-lily pond, and expanded the potager, to name just a few additions. She was still paying rent at her apartment at 53 Rue de Varenne, in Paris—a grand flat festooned with carved-wood cherubs and ornate fireplaces. The costs added up.

When she began writing “The Age of Innocence,” in September, 1919, Edith Wharton needed a best-seller. The economic ravages of the First World War had cut her annual income by about sixty per cent. She’d recently bought and begun to renovate a country house, Pavillon Colombe, in Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt, where she installed new black-and-white marble floors in the dining room, replaced a “humpy” lawn with seven acres of lavish gardens, built a water-lily pond, and expanded the potager, to name just a few additions. She was still paying rent at her apartment at 53 Rue de Varenne, in Paris—a grand flat festooned with carved-wood cherubs and ornate fireplaces. The costs added up.

Wharton recognized her place in the pyramid of the super-rich: tantalizingly close to the pinnacle, but never quite there. (For her, a difficult financial decision would take the shape of having to give up plans for ornate iron gates at the Mount, her thirty-five-room mansion in Massachusetts.) To continue to live as she was accustomed, she needed a new hit. “The Age of Innocence,” which Wharton produced in seven months, offered her the chance to make money by writing about money—a return to form after four years of war stories that, her publishers frankly told her, weren’t selling. From her perch thousands of miles from the gatekeepers of New York society, and nearly fifty years on from the eighteen-seventies setting she had chosen, Wharton invited the hoi polloi right into the living rooms of Manhattan’s upper crust, for an insider’s exposé. “Fate had planted me in New York,” she writes in her memoir, “A Backward Glance,” “and my instinct as a story-teller counselled me to use the material nearest to hand.”

More here.

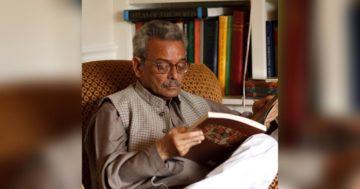

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi (1935-2020): Why this death leaves a permanent patch of darkness in literature

Maaz Bib Bilal in Scroll In:

This annus horribilis is not over yet, and it has now taken away from us the greatest doyen and scholar of Urdu literature the world knew over the recent decades, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi. He died peacefully at his home, surrounded by his family and his favourite dogs, having recovered earlier this month from Covid-19. I had the honour and pleasure to visit him in his study in January this year, which isn’t anything less than a library. It is hard to imagine all those books siting there without their avid reader. Ghalib’s often quoted verse “aisā kahan se laun ki tujh saa kahen jise” – “where do I find another who may be like you?” – doesn’t seem to hold truer than in this moment of the greatest loss for Urdu culture.

This annus horribilis is not over yet, and it has now taken away from us the greatest doyen and scholar of Urdu literature the world knew over the recent decades, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi. He died peacefully at his home, surrounded by his family and his favourite dogs, having recovered earlier this month from Covid-19. I had the honour and pleasure to visit him in his study in January this year, which isn’t anything less than a library. It is hard to imagine all those books siting there without their avid reader. Ghalib’s often quoted verse “aisā kahan se laun ki tujh saa kahen jise” – “where do I find another who may be like you?” – doesn’t seem to hold truer than in this moment of the greatest loss for Urdu culture.

Poet, novelist, critic, literary historiographer, translator, editor, publisher, professor, literary modernist as well as postcolonial revivalist of traditions – it is a long list of literary and cultural roles that he performed exquisitely alongside his job with the Indian postal services till his retirement in 1994 and thereafter. It is tough to prioritise one aspect of Faruqi’s literary impact over the others, but what he brought to all the different sides of his prolific career was the capacity to be a revisionist, a field-changing observer, who managed to change the purviews of aesthetics, criticism, and literary history through his rigorous scholarship.

More here. (Note: Via Bibi)

Can Wall Street’s Heaviest Hitter Step Up to the Plate on Climate Change?

Bill McKibben in The New Yorker:

Bill McKibben in The New Yorker:

he year is coming to an end, and all eyes are trained on D.C., as Joe Biden prepares to helm a venerable enterprise with a four-trillion-dollar budget. On the climate front, Biden’s team, which he announced last week, with Gina McCarthy, Deb Haaland, Jennifer Granholm, and John Kerry at the forefront, seems highly credible—a hundred-and-eighty-degree shift from the coterie of coal lobbyists and oil-industry operatives that have decorated the current Administration. Biden’s group has a real shot at getting Washington squarely in the global-warming fight. But, although that federal effort will doubtless occupy much of our attention in the year ahead, let’s close out 2020 by examining the de-facto government based on Wall Street. Its obvious head is BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, which is—just for purposes of scale—an eight-trillion-dollar enterprise, and the largest shareholder in almost every company that matters to the future of the Earth. BlackRock is a monetary heavy hitter.

To continue the baseball analogy, BlackRock finally stepped up to the climate plate this year. Larry Fink, the C.E.O., focussed his annual letter to investors on global warming, promising that henceforth sustainability would be at the heart of investment decisions. For that stand, Fink was recently named the first Institutional Investor of the Year—by Institutional Investor magazine. This encomium seems a little like awarding the season’s M.V.P. during spring training, simply because an intrepid player announces his plan to bat .400. In point of fact, BlackRock mostly whiffed on climate last year: the activist group Majority Action reports that, during proxy season, when BlackRock’s votes would have made a real difference, the firm voted to elect ninety-nine per cent of the directors proposed for boards at energy companies and utilities, even if the companies had made no serious climate commitments.

More here.

The Limits of State Capitalism on China’s Bid for Hegemony

Mingtang Liu and Kellee S. Tsai in the Marxist Sociology blog:

Mingtang Liu and Kellee S. Tsai in the Marxist Sociology blog:

China’s stunning economic growth and technological prowess have stoked anxiety that the world’s longest-surviving communist regime is poised to replace the United States as the next global hegemon. Coupled with the expectation that China may emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic less scathed than the West, to many observers the scenario of a US-China power transition appears even more likely, if not inevitable.

We disagree. In a recent article, we detail why much of the current discourse on China’s rise significantly overstates its economic might. China’s model of state capitalism and the dynamics of globalization have contributed to its rapid development over the past four decades. Yet these same factors circumscribe its hegemonic potential for three main reasons.

First, in China’s version of state capitalism, private capital faces serious constraints because the state sector constitutes the economic bedrock of the Chinese Communist Party’s ruling status. State-owned enterprises have been backstopped by the state banking system and shielded by powerful regulators—despite their lower levels of productivity. By contrast, the more efficient private sector has grappled with limited access to official sources of credit and relied on more expensive and riskier types of informal finance.

More here.

A More Perfect Meritocracy

Agnes Callard in Boston Review:

Agnes Callard in Boston Review:

We have some say in how our lives go, and yet our lives are also subjected to forces outside our control. Which part of this story do we emphasize? Conservatives tend to see the glass as half full, stressing both agential control over outcomes and personal responsibility for them. Progressives are more likely to highlight the causal role of outside factors—even when those factors are in some sense “internal,” such as one’s genetic makeup—and to caution us to err on the side of withholding blame for poor outcomes.

Educator and essayist Fredrik deBoer argues that there is one domain where this political pattern breaks down: in conversations about academic achievement. In the introduction to his new book The Cult of Smart, deBoer articulates the puzzle by drawing on blogger Scott Alexander’s memory of having been praised for getting A in English but blamed for getting a C- in calculus:

Every time I was held up as an example in English class, I wanted to crawl under a rock and die. I didn’t do it! I didn’t study at all, half the time I did the homework in the car on the way to school, those essays for the statewide competition were thrown together on a lark without a trace of real effort. To praise me for any of it seemed and still seems utterly unjust.

On the other hand, to this day I believe I deserve a fricking statue for getting a C- in Calculus I. It should be in the center of the schoolyard, and have a plaque saying something like “Scott Alexander, who by making a herculean effort managed to pass Calculus I, even though they kept throwing random things after the little curly S sign and pretending it made sense.”

Why, Alexander wonders, should praise and blame track what is clearly innate?

More here.

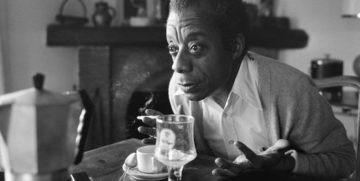

The Anti-Colonial Vision of James Baldwin’s Last Two Unfinished Works

Bill V. Mullen in Literary Hub:

In 1985, Baldwin’s published and some unpublished essays were gathered in a single volume titled The Price of the Ticket. The book was significant for both looking backward, retrospectively and in a monumental manner, at the whole of Baldwin’s life, and forward, to the beginnings of the process of his memory and commemoration. By 1985, Baldwin’s literary production had become relatively meager. He was tired, winding down, traveling less, and camping out mainly at St. Paul-de-Vence. The lover he had lost to AIDS, according to David Leeming, died with him there, his ashes scattered around the property’s garden.

Baldwin was committed to two writing projects in these closing years of his life. The first, begun years earlier, was titled No Papers for Muhammad. According to Baldwin biographers James Campbell and David Leeming, the novel was to be based on Baldwin’s own frightening encounter with French immigration authorities—one perhaps fictionalized in David’s near apprehension by the police in “Les Evade’s”—and on the case of an Arab friend deported to Algeria.

Baldwin never completed the novel. However, important kernels and seedlings from it did manifest themselves in what became his final creative project, a play entitled The Welcome Table. Magdalena Zaborowska, in her superb book on Baldwin’s Turkish decade, refers to Baldwin’s The Welcome Table as a “last testament” to major life themes, including exile, erotics, and the multiple identities of the diasporic black subject. It is also, as Joseph Vogel noted, the only place in his creative writing where Baldwin made reference to the AIDS/HIV crisis.

More here.

The Revolutionary Humanism of Frantz Fanon

Peter Hudis in Jacobin:

Peter Hudis in Jacobin:

The renewed protests against racism and police brutality over the last year have supplied a fresh impetus for thinking about the nature of capitalism, its relationship to racism, and the construction of alternatives to both. Few thinkers speak more directly to such issues than Frantz Fanon, the Martinican philosopher, psychiatrist, and revolutionary who is widely considered one of the twentieth century’s foremost thinkers on race and racism.

Fanon had direct experience of French colonial rule, from the Caribbean to North Africa, and brought that experience to bear on his intellectual work. He played an active role in the Algerian revolutionary movement that struggled for independence in the 1950s, but he warned that independent African states would simply replace the colonial system with a national bourgeoisie unless they followed the path of social revolution.

Some of Fanon’s key works have been available in English translation for many years. However, the recent publication of over six hundred pages of Fanon’s previously unavailable writings on literature, psychiatry, and politics makes this a fitting moment to reexamine his thought anew.

More here.

Most parents are not evil – they’re lovely people with the wrong tools

Hadley Freeman in The Guardian:

When Philippa Perry finished, after several years of writing and a lifetime of research, the first draft of her book about improving relationships between parents and children, she sent it to her editor – and their relationship promptly collapsed.

When Philippa Perry finished, after several years of writing and a lifetime of research, the first draft of her book about improving relationships between parents and children, she sent it to her editor – and their relationship promptly collapsed.

“She felt really told off by the book. She has teenagers and, of course, sometimes she would tell them: ‘Get out of bed, you lazy sods!’ So what I wrote went straight into her heart,” says Perry, who very much does not advocate calling one’s children “lazy sods”. This must have been painful for you to hear, I say. “Actually, it was amazing feedback,” she replies with the good cheer of a psychotherapist who firmly believes painful moments can beget productive solutions. “I realised that my own anger towards my parents had leaked out into the book. So I rewrote it and it’s a better book.” And how do matters stand with her editor? “Relationships are often about rupture and repair, and we have very much repaired.”

The result of all this rupturing and repairing was the ingeniously titled The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read (and Your Children Will Be Glad That You Did), which became one of this year’s publishing success stories, its distinctive orange and blue cover as omnipresent in a certain type of family home as Ella’s Kitchen organic baby food and Cosmic Kids Yoga.

Out in paperback next week, it is Perry’s third book – after Couch Therapy (2010) and How to Stay Sane (2012) – and her most successful. To date, it has sold more than 240,000 copies and it’s not hard to see why: she writes with a thoughtful, inquisitive elegance rarely found in parenting guides, which tend more to dry didacticism. Despite her revisions, the book is still firm with parents but also forgiving (ruptures can be repaired), full of the currently popular attachment-parenting theories (children’s needs come first) while chucking in some common sense (sometimes parents need a break). Most of all, it is incisive and persuasive – God, it’s persuasive. I’ve yet to meet a parent who hasn’t altered their parenting to some degree after reading it, myself extremely included.

More here.

He Reported on Pakistan’s Volatile Politics. Then He Became a Story Himself

Amna Nawaz in The New York Times:

The question has confounded many: How does Pakistan stay alive?

The question has confounded many: How does Pakistan stay alive?

The 73-year-old nation born of a bitter postcolonial divorce has heaved through humiliating defeats, careened from coup to coup and stubbornly endured despite relentless forces working to unweave it.

How?

The New York Times foreign correspondent Declan Walsh is the latest to try to answer that question. In his new book, “The Nine Lives of Pakistan: Dispatches From a Precarious State,” he pulls from years of contact with sources on the ground, presenting nine narratives — each given its own chapter — to paint a vivid, complex portrait of a country at a crossroads.

This nuclear-armed nation is today the fifth most populous in the world. Its subcontinental perch grants it strategic geopolitical importance. And though its past wars with India seem to consume Pakistan’s almighty army leaders, for the past two decades it’s largely been America’s war in neighboring Afghanistan that’s demanded their attention. Walsh spent nearly a decade living in and covering Pakistan, first for The Guardian, then for The Times. His tenure coincided with some of the country’s most turbulent modern years: fraught elections, assassinations and military rule; a war next door and within; and a tenuous alliance with the United States fraying to the breaking point, particularly after American Special Forces found Osama bin Laden hiding inside Pakistan, and killed him.

More here.

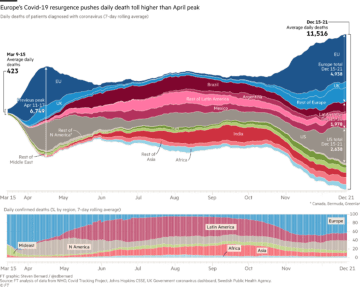

Coronavirus tracker: the latest world figures as countries fight Covid-19 resurgence

From the Financial Times:

The human cost of coronavirus has continued to mount, with more than 77m cases confirmed globally and more than 1.69m people known to have died.

The human cost of coronavirus has continued to mount, with more than 77m cases confirmed globally and more than 1.69m people known to have died.

The World Health Organization declared the outbreak a pandemic in March and it has spread to more than 200 countries, with severe public health and economic consequences. This page provides an up-to-date visual narrative of the spread of Covid-19, so please check back regularly because we are refreshing it with new graphics and features as the story evolves.

More here.

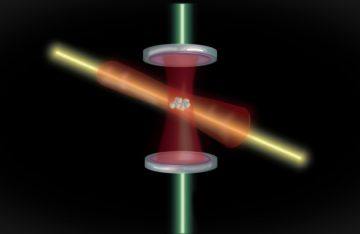

A new Type of Atomic Clock Would be off by 100 Milliseconds Since the Beginning of the Universe

From Universe Today:

Although the modern standard is officially exact, it isn’t actually exact. Two atomic clocks of the same design keep slightly different times. By statistically comparing atomic clocks, we know they are accurate to about one second in thirty million years. That’s probably accurate enough for everyday use, but it isn’t accurate enough for some scientific purposes. If we had more precise clocks, we could use them to study everything from geology to dark energy. So there is an ongoing quest to develop a new, more accurate standard.

Although the modern standard is officially exact, it isn’t actually exact. Two atomic clocks of the same design keep slightly different times. By statistically comparing atomic clocks, we know they are accurate to about one second in thirty million years. That’s probably accurate enough for everyday use, but it isn’t accurate enough for some scientific purposes. If we had more precise clocks, we could use them to study everything from geology to dark energy. So there is an ongoing quest to develop a new, more accurate standard.

Most of the approaches look toward purely optical methods, but new work in Nature uses atoms in quantum entanglement. One of the reasons modern atomic clocks aren’t perfect is that the atoms recoil when light is emitted, which shifts the frequency of emitted light slightly. If the atom could be kept perfectly stationary when it emits light, then the frequency of the light would be exact. But quantum mechanics keeps the position of an atom a bit fuzzy, meaning that the frequency of emitted light is also a bit fuzzy. This effect is known as the standard quantum limit.

To address this problem, the team uses an effect known as quantum entanglement.

More here.

The Biology of Mistletoe

Rachel Ehrenberg in Smithsonian:

Some plants are so entwined with tradition that it’s impossible to think of one without the other. Mistletoe is such a plant. But set aside the kissing custom and you’ll find a hundred and one reasons to appreciate the berry-bearing parasite for its very own sake. David Watson certainly does. So enamored is the mistletoe researcher that his home in Australia brims with mistletoe-themed items including wood carvings, ceramics and antique French tiles that decorate the bathroom and his pizza oven. And plant evolution expert Daniel Nickrent does, too: He has spent much of his life studying parasitic plants and, at his Illinois residence, has inoculated several maples in his yard — and his neighbor’s — with mistletoes. But the plants that entrance these and other mistletoe aficionados go far beyond the few species that are pressed into service around the holidays: usually the European Viscum album and a couple of Phoradendron species in North America, with their familiar oval green leaves and small white berries. Worldwide, there are more than a thousand mistletoe species. They grow on every continent except Antarctica — in deserts and tropical rain forests, on coastal heathlands and oceanic islands. And researchers are still learning about how they evolved and the tricks they use to set up shop in plants from ferns and grasses to pine and eucalyptus.

Some plants are so entwined with tradition that it’s impossible to think of one without the other. Mistletoe is such a plant. But set aside the kissing custom and you’ll find a hundred and one reasons to appreciate the berry-bearing parasite for its very own sake. David Watson certainly does. So enamored is the mistletoe researcher that his home in Australia brims with mistletoe-themed items including wood carvings, ceramics and antique French tiles that decorate the bathroom and his pizza oven. And plant evolution expert Daniel Nickrent does, too: He has spent much of his life studying parasitic plants and, at his Illinois residence, has inoculated several maples in his yard — and his neighbor’s — with mistletoes. But the plants that entrance these and other mistletoe aficionados go far beyond the few species that are pressed into service around the holidays: usually the European Viscum album and a couple of Phoradendron species in North America, with their familiar oval green leaves and small white berries. Worldwide, there are more than a thousand mistletoe species. They grow on every continent except Antarctica — in deserts and tropical rain forests, on coastal heathlands and oceanic islands. And researchers are still learning about how they evolved and the tricks they use to set up shop in plants from ferns and grasses to pine and eucalyptus.

All of the species are parasites. Mistletoes glom on to the branches of their plant “hosts,” siphoning off water and nutrients to survive. They accomplish this thievery via a specialized structure that infiltrates host tissues. The familiar holiday species often infest stately trees such as oaks or poplar: In winter, when these trees are leafless, the parasites’ green, Truffula-like clumps are easy to spot dotting their host tree’s branches. Yet despite their parasitism, mistletoes may well be the Robin Hoods of plants. They provide food, shelter and hunting grounds for animals from birds to butterflies to mammals — even the occasional fish. Fallen mistletoe leaves release nutrients into the forest floor that would otherwise remain locked within trees, and this generosity ripples through the food chain.

More here.