Clair Wills at the NYRB:

“Ordinary time” is that part of the liturgical calendar, between Easter and Advent, when nothing much happens. But ordinariness also stands for life lived under temporal constraints, for the commonplace experience of being human. Questions of free will and the shape given to private thoughts and desires hover at the margins of both of these novels. And it cannot be a coincidence that in both novels those questions are posed by a clerk who takes on the role of a priest, without having the authority to administer the sacraments or to shrive sins. In The Corner That Held Them, the false priest is Ralph Kello, a clerk who turns up at the convent gate in 1349, claiming to be a priest because he is hungry, and who becomes trapped by his lie for thirty years. In To Calais, it is Thomas, a religious scholar but not an ordained priest, who is forced by circumstance to hear the last confessions of dying victims of the plague. In the act of confessing to the living, rather than to God, whose pardon is required? In the absence of the sacrament, the confessions are nothing but stories—nothing more or less than a means for people to ask forgiveness of one another, and to give it. In this scenario confessing is like talking, or thinking, and the basis of enlightenment measured on a human, and ordinary, scale.

more here.

The primary difficulty of interstellar communication is finding common ground between ourselves and other intelligent entities about which we can know nothing with absolute certainty. This common ground would be the basis for a universal language that could be understood by any intelligence, whether in the Milky Way, Andromeda, or beyond the cosmic horizon. To the best of our knowledge, the laws of physics are the same throughout the universe, which suggests that the facts of science may serve as a basis for mutual understanding between humans and an extraterrestrial intelligence. One key set of scientific facts presents an intriguing question. If aliens were to visit Earth and learn about its inhabitants, would they be surprised that such a wide variety of species all share a common genetic code? Or would this be all too familiar? There is probable cause to assume that the structure of genetic material is the same throughout the universe and that, while this is liable to give rise to life forms not found on Earth, the variety of species is fundamentally limited by the constraints built into the genetic mechanism.

The primary difficulty of interstellar communication is finding common ground between ourselves and other intelligent entities about which we can know nothing with absolute certainty. This common ground would be the basis for a universal language that could be understood by any intelligence, whether in the Milky Way, Andromeda, or beyond the cosmic horizon. To the best of our knowledge, the laws of physics are the same throughout the universe, which suggests that the facts of science may serve as a basis for mutual understanding between humans and an extraterrestrial intelligence. One key set of scientific facts presents an intriguing question. If aliens were to visit Earth and learn about its inhabitants, would they be surprised that such a wide variety of species all share a common genetic code? Or would this be all too familiar? There is probable cause to assume that the structure of genetic material is the same throughout the universe and that, while this is liable to give rise to life forms not found on Earth, the variety of species is fundamentally limited by the constraints built into the genetic mechanism. Julian Lucas: Your introductory essay suggests that when it comes to King, contemporary thought is held “captive by a picture.” Do you think that there can be a coexistence between King the political icon and King the serious philosophical thinker?

Julian Lucas: Your introductory essay suggests that when it comes to King, contemporary thought is held “captive by a picture.” Do you think that there can be a coexistence between King the political icon and King the serious philosophical thinker? Physics is simple; people are complicated. But even people are ultimately physical systems, made of particles and forces that follow the rules of the

Physics is simple; people are complicated. But even people are ultimately physical systems, made of particles and forces that follow the rules of the  As the world’s business elites trek to Davos for their annual gathering, people should be asking a simple question: Have they overcome their infatuation with US President Donald Trump?

As the world’s business elites trek to Davos for their annual gathering, people should be asking a simple question: Have they overcome their infatuation with US President Donald Trump? Last week, my parents saw Little Women. My mother immediately phoned me. “I think Professor Bhaer is Jewish,” she said, her voice vibrating with barely suppressed excitement. I said I didn’t think the facts supported this theory. But several days later, I got an email from her with the subject line “FYI!!!” When I clicked on the link, I saw it was

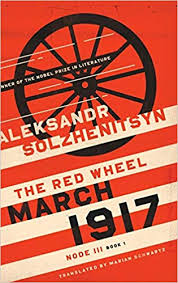

Last week, my parents saw Little Women. My mother immediately phoned me. “I think Professor Bhaer is Jewish,” she said, her voice vibrating with barely suppressed excitement. I said I didn’t think the facts supported this theory. But several days later, I got an email from her with the subject line “FYI!!!” When I clicked on the link, I saw it was  Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s multivolume historical novel about the Russian Revolution, The Red Wheel, is divided into four “nodes,” each a lengthy account of a short span of time. March 1917, the third node, is in turn divided into four volumes, the second of which is the book under review, translated into English for the first time. Combining nonfictional historical argument with novelistic accounts of the principal historical actors and a few fictional characters, March 1917 covers a mere three days of unrest and revolution, March 13–15, 1917, at the end of which Tsar Nicholas II abdicates, ending the Romanov dynasty in Russia. Marian Schwartz’s splendid translation captures the prose’s powerful pace and conveys, as few translators could, the author’s subtle use of tone.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s multivolume historical novel about the Russian Revolution, The Red Wheel, is divided into four “nodes,” each a lengthy account of a short span of time. March 1917, the third node, is in turn divided into four volumes, the second of which is the book under review, translated into English for the first time. Combining nonfictional historical argument with novelistic accounts of the principal historical actors and a few fictional characters, March 1917 covers a mere three days of unrest and revolution, March 13–15, 1917, at the end of which Tsar Nicholas II abdicates, ending the Romanov dynasty in Russia. Marian Schwartz’s splendid translation captures the prose’s powerful pace and conveys, as few translators could, the author’s subtle use of tone. The last time we heard from Bombay Bicycle Club, they’d gone out on a high. 2014’s So Long, See You Tomorrow, their fourth album, was their first to reach number one. Their final show before they announced a hiatus in January 2016 was also the last ever gig at London’s 19,000-capacity Earl’s Court – a historic, confetti-fuelled moment before the bulldozers came in to flatten 40 years of rock history.

The last time we heard from Bombay Bicycle Club, they’d gone out on a high. 2014’s So Long, See You Tomorrow, their fourth album, was their first to reach number one. Their final show before they announced a hiatus in January 2016 was also the last ever gig at London’s 19,000-capacity Earl’s Court – a historic, confetti-fuelled moment before the bulldozers came in to flatten 40 years of rock history. AN ANTIMODERNIST

AN ANTIMODERNIST Earlier this month, the American Cancer Society announced its latest figures on cancer incidence and mortality

Earlier this month, the American Cancer Society announced its latest figures on cancer incidence and mortality For the last three years, I have struggled with a dilemma: As a reasonable, quite liberal person, what should I think of my 60 million fellow Americans who voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and the vast majority of whom continue to support him today? Normally, a personal dilemma is a private thing, not a topic for public airing, but I feel that this particular problem is one the vexes many others – perhaps even a majority of Americans, as more of us voted for Hillary Clinton and many did not vote at all. Since that bleak day in November 2016, an unspoken – and sometimes loudly spoken – question hangs in the air: What kind of “

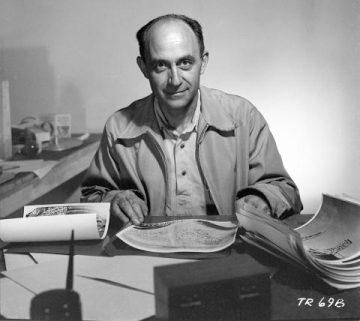

For the last three years, I have struggled with a dilemma: As a reasonable, quite liberal person, what should I think of my 60 million fellow Americans who voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and the vast majority of whom continue to support him today? Normally, a personal dilemma is a private thing, not a topic for public airing, but I feel that this particular problem is one the vexes many others – perhaps even a majority of Americans, as more of us voted for Hillary Clinton and many did not vote at all. Since that bleak day in November 2016, an unspoken – and sometimes loudly spoken – question hangs in the air: What kind of “ In November 1918, a 17-year-student from Rome sat for the entrance examination of the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy’s most prestigious science institution. Students applying to the institute had to write an essay on a topic that the examiners picked. The topics were usually quite general, so the students had considerable leeway. Most students wrote about well-known subjects that they had already learnt about in high school. But this student was different. The title of the topic he had been given was “Characteristics of Sound”, and instead of stating basic facts about sound, he “set forth the partial differential equation of a vibrating rod and solved it using Fourier analysis, finding the eigenvalues and eigenfrequencies. The entire essay continued on this level which would have been creditable for a doctoral examination.” The man writing these words was the 17-year-old’s future student, friend and Nobel laureate, Emilio Segre. The student was Enrico Fermi. The examiner was so startled by the originality and sophistication of Fermi’s analysis that he broke precedent and invited the boy to meet him in his office, partly to make sure that the essay had not been plagiarized. After convincing himself that Enrico had done the work himself, the examiner congratulated him and predicted that he would become an important scientist.

In November 1918, a 17-year-student from Rome sat for the entrance examination of the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy’s most prestigious science institution. Students applying to the institute had to write an essay on a topic that the examiners picked. The topics were usually quite general, so the students had considerable leeway. Most students wrote about well-known subjects that they had already learnt about in high school. But this student was different. The title of the topic he had been given was “Characteristics of Sound”, and instead of stating basic facts about sound, he “set forth the partial differential equation of a vibrating rod and solved it using Fourier analysis, finding the eigenvalues and eigenfrequencies. The entire essay continued on this level which would have been creditable for a doctoral examination.” The man writing these words was the 17-year-old’s future student, friend and Nobel laureate, Emilio Segre. The student was Enrico Fermi. The examiner was so startled by the originality and sophistication of Fermi’s analysis that he broke precedent and invited the boy to meet him in his office, partly to make sure that the essay had not been plagiarized. After convincing himself that Enrico had done the work himself, the examiner congratulated him and predicted that he would become an important scientist.

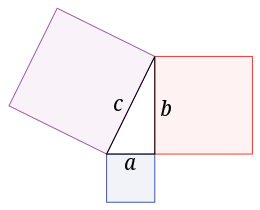

I have some very simple New Year’s resolutions, and some that require an entire column to spell out. One example of the latter is that I want to make a subtle but meaningful change in how I talk to my (middle and high school) math students about proofs.

I have some very simple New Year’s resolutions, and some that require an entire column to spell out. One example of the latter is that I want to make a subtle but meaningful change in how I talk to my (middle and high school) math students about proofs.